Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: chicago, Comics, entertainment, fantagraphics, Glenn Head, indie Comics, memoir, R. Crumb

'Chicago' Takes Us From Suburbia To The 70's Comics Underground – Glenn Head's Memoir Tells All

Glenn Head has completed a six year odyssey in autobiographical narrative, but the genesis of the story, and his knowledge that someday he'd complete it in comics form, have spanned decades. Long time comics creator in the short form through mini-comics and anthologies, also acting as an editor of anthologies, Head is now releasing his first full length book through Fantagraphics this autumn: Chicago.

I spoke to Glenn Head about his new book and he revealed many insights into his working process on the book and how completing such a substantial memoir has affected him as a comics creator.

Hannah Means-Shannon: Was it difficult to make a decision to work on a longform story about specific parts of your youth? Did you feel resistant to revisiting all that or was this a story you knew you'd try to tell as a whole someday?

I wasn't at all self-conscious about it…I wasn't really thinking about it poetically, and I sure wasn't doing it so I could write about it! I really had no idea I'd be starving, dirty, homeless, trying to ward off sexual predators, barely surviving. I had no idea at all.

Working in long form was a challenge, but it was also something that really interested me. So much in comics—even in long form—is about compression, simplifying, trying to make less do more, that I was intrigued by trying to do something of greater depth.

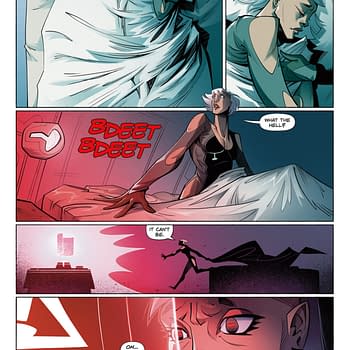

One thing that interests me about the graphic novel is the possibility of really working with the different layers of perception and feeling that can happen. Comics in short form have a tendency narrative-wise to just get really propulsive; push the story! Move characters! Make the action happen! Forward motion all the time!! This was really the first time where I attempted to really open things up—make the reader feel what it's like for the character—me—to go through a lot of emotional states … some of them disturbed … I mean, that's weird to draw but also an exciting challenge at the same time. There are no wisecracks here, no snappy attempts at distance or cheap aggression. I really wanted this to read—and feel—like lived experience. Because it was.

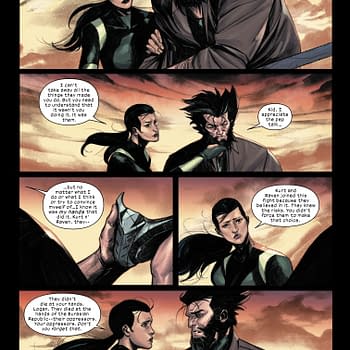

GH: I wouldn't say the style was specifically chosen for the subject matter. Not exactly. But I did like the fact this intensely-detailed, Underground comix-influenced drawing was, in the story, about actually meeting these guys who originated it! I wanted it to feel like this wanna-be Underground cartoonist is kind of "coming home," but that the home he arrives at is a pretty harsh place. I wanted it to be pretty clear that this suburban kid's trip into another world doesn't have a soft landing. That was important. So yeah, I wanted all these things to connect up.

Having said that this really is just the way I draw. Believe it or not I am for simplicity, and I love the noir atmosphere and terseness of old Dick Tracy comics … for me though, the details always creep in! I've just gotta draw the cracks on the sidewalk, the dogshit, the graffiti, the garbage cans…I mean I might try and get all of those details into a huge, full-page drawing if need be…but the atmosphere, the tone of a time and place—I work really hard at getting that.

The page that hints at an earlier style is a one-page strip that I actually did draw back then, called Chicago Rooming House. It originated as a one-page, eight-line poem by Jack Michelin. I drew it then in exchange for room and board at some sleazy motel. I included it for reasons of authenticity—it brings the viewer right back to where I was at that time. That's pretty much how I drew then.

The elements of style that relate to the subject matter? Well I guess in one way I'm kind of a not-quite-primitive artist. My drawing style has a kind of 'grit' to it, that I think reflects the street level quality of the story—there's an intensity in my focus as an artist, the drawing style brings you in very close to the subject matter itself. So if there's a roughness—a rawness—about my visuals…I think that's appropriate for the story itself.

HMS: You've worked a lot in shorter forms and anthologies. Did your strategy for working on CHICAGO build on smaller units? What observations do you have for cartoonists about constructing and following through on a project like this?

Cartoonists thinking about following through on a project like this? Take your time with it! It took me six years, maybe more to draw Chicago.

That's the first thing. The second thing is don't be afraid of the material. From where I stand, there's no way and no reason for doing memoir comics unless you're facing something and facing it squarely. Otherwise what's the point?

That's not saying everybody has to work like that…but I can't see much reason for auto-bio unless you're really willing to open up. You have to. In a way the memoir is ultimately about unburdening yourself. Putting your story—your material—on the page and letting go of it.

GH: A lot of the details here are just the way I remember things…what I saw around me at the time. There are these scenes of me on the streets … they're sort of borderline psychedelic…I love drawing scenes like that because what they're really about is what homelessness felt like—as seen through some kind of crazy horror-house distorting mirror. So what I'd say is that a lot of these details are just about what felt right for these '70s scenes.

And yeah, I did do a good bit of photo research for this book. I flew out to Chicago to snap a lot of pictures—of both the North and South sides. They were invaluable to me. And I watched and re-watched a lot of 1970s crime movies! Scorsese…some blaxploitation. Cities were different then. The filth was everywhere—just accepted as part of the landscape. I wanted to capture that. I want to be sure I'm getting the scene right. And the tone.

HMS: What made you decide to use two time periods in the story? Was that part of the deep structure of the story and always intended?

GH: The decision to use two time periods was actually one that was just kind of visited upon me. The character of Sarah—the part where we reconnect—that part of the story happened in 2010, so I knew that would bring the story up-to-date. It actually allowed me to put her in the story in the first place, bring in the romantic element…I hadn't originally planned to…the first part of Chicago that I drew was the middle chapter—Chicago itself—because I couldn't come up with a way to start the book, aside from knowing that it started with me in the graveyard laughing…I know that may sound a bit convoluted…

But I really think the book needed to take place in those two time periods…I couldn't just show that early time period, and have it end there, kind of a "Wow, hey those sure were some f*cked up years weren't they?!" There had to be a reckoning, a bringing up to date, a way of looking at all this, like just how exactly were Glen and Sarah's lives affected by their earlier lives?

The early parts of the book show Glen laughing in the graveyard…what is he laughing at? Life itself? The fact that we all end up here? It's unclear…but it seems that both Glen and Sara are heading towards some kind of difficult moments, dangerous most likely…she's already sold her body for money at seventeen, no less, he's looking for a life where things aren't "safe" like his own. What happens when he finds this?

I wanted to show that the paths these two laid down in their early years are no simple things, occurrences that just happened to them. They were things that set their lives in motion. As we see in the final chapter.

HMS: Do you feel that your experiences trying to figure out your involvement in comics is something others will relate to, or is the uniqueness of your specific experiences a motivating thing in telling your stories?

GH: I think people will be able to relate to my experience with comics not so much literally—unless they're cartoonists, maybe—as metaphorically. To have some dream, what it is you want to be, want to do, at any cost, regardless of the price and even more regardless of the lack of benefit…that's what the idea of Underground comics was to me as a teenager.

Of course that doesn't mean that everybody can relate to chasing after an absurdly unrealistic dream, which in fact drawing comics kind of is! Even more than a rock 'n' roll fantasy which is like, you know…some people actually do have some orgasmic-thrill-ride-mega-millions-hit record-f*ck all the groupies, and fashion-models kind of experience. But really you can't get that in comix! Even as a fantasy things don't get that thrillingly out there!

One thing I think happens though, is everybody gets their face rubbed in it. Whatever you want, whatever your heart desires, there's a price for it…And that's the "coming of age" part. If we're lucky "time happens" as Glen says late in the story. If we're not, we don't even get that far. But maybe things get better and we move on, I guess.

Of course, the uniqueness of my experiences motivate me—they're mine! I've gotta tell 'em before I die! And yeah, that in itself is a motivating factor—it takes time to draw this stuff!

HMS: There are some really intense scenes that depict psychological states as well as action—I'm particularly thinking of things like dreaming about food or finding your Dad's gun. It's great how you balance showing action with giving equal weight to perception and state of mind. What are some of the ways you tackle that balance as a cartoonist?

GH: Well, capturing the psychological state of my character, myself really, was very important to me in this work. There are parts of the book where the action is very simple and the motivations are right on the surface—they don't need to go deep. They're external. That's especially true in the early parts of the book. I'm driven to escape the suburbs and I'm in love with Sarah. The ball gets rolling from that.

The psychological state of my character shows up as subject matter when those actions give him something to consider, to really think about. In other words it's the aftermath of some of his more impulsive un-thought-out behavior that finally gets him thinking. He wanted a different world and now that he's walking around in it he finds out how painful that is. He finds out literally what hunger is…It's the results of his behavior and how he feels about it that I find interesting enough to want to delve into.

Likewise the chapter where Glen is toying with his father's handgun…someone shooting a gun for kicks, everyone does that at some point, but what's interesting for me is the emotional state of the person with the gun, and if that state is somewhat unstable, well, so much the better, there's more at stake…what's he going to do with the gun? Who's he going to shoot? He's naked, he's alone with it, he's at a very low ebb…his life has emptied out. It's people like that, you wonder what they might do with a firearm. How far will they go? That's what I was trying to express psychologically.

GH: I would say that what's scariest and most rewarding about doing a book like this…they are really one and the same. The fact that I'm actually expressing something that is so personal…I always wanted to tell this story, all the different parts to it…I don't know if I wanted to unburden myself, but yes probably that too…Mainly I really wanted to delve into this time in my life that touched me very deeply. And I wanted to do this in a very ambitious way, which I have, so that's very satisfying.

And now it's done and it's published! The finished product is great to see…Fantagraphics does a great job with the stuff they put out, my book was no exception…it's a terrific print job, great production, I'm very happy with how it looks. It's also the first book I've done… I've done a lot of comics, you know, what they call pamphlets—32-page books, or even much larger anthologies I've edited—but this is a real book so that in itself is very exciting.

But I won't kid you, doing a book with this kind of personal information…I make myself very vulnerable, really put myself out there…I know that's done in the memoir, people really put everything out there, but I haven't. You know, I'm also a New Yorker and the whole let-it-all-hang-out thing…there's less of that going on around here in the comics scene, the one I know than maybe elsewhere…like, I guess these Canadians…it's all memoir all the time for them! In the big bad city of New York you cover your ass, you don't give an inch, you don't give anything away! Well, that's no longer true for me…it's all out there!

Chicago releases through Fantagraphics books at 168 pages in hardcover on September 19th.