Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: 1990s, Batman, bernie wrightson, bill mantlo, chuck dixon, comic cons., Comics, Danny Fingeroth, Don Bluth, doug moench, Dragon's Lair, entertainment, jim starlin, M D Bright, Marvel Saga, Mr. T, MST3K, neal adams, Peter Sanderson, The Dark Knight Returns, the hulk

Four Color Roots Part 5: A Misspent Youth At Early '90s Comic Cons

By Christopher Smith

In this, the fifth installment of our ongoing column series, Christopher Smith takes us on a tour through his own back pages as a comics fan, going down unexpected dark alleys and digressions. Focusing only on the comics and pop-cultural touchstones he experienced at the time, he reconsiders their (at times unlikely) influence and impact from a modern-day context, and his own journey through the four-color and geek culture worlds that's apropos of so many comics fans and pros of the same generation.

Last time, he looked at the seismic upheaval of 1992's Image Comics emergence, and the landmark Batman: The Animated Series. In this installment, an interlude of sorts from the chronological run-through, our author attends his first comic conventions in the Tri-State Area, circa 1993…

As we sat at formica-topped tables and ate greasy sleazeburgers, Pynchon slouched in the booth, long thin legs in green Levi's sprawled out, pensively biting his nails. Then he ripped a styrofoam coffee cup into tiny, meticulous shreds. He had dissipated, tired eyes like Robert Mitchum's.

– Andrew Gordon, Smoking Dope with Thomas Pynchon: A Sixties Memoir

In 1993, I met Doug Moench face-to-face at a comic convention held in a few drab, unimpressive carpeted rooms of a Sheraton Hotel in Wilmington, Delaware. My plastic goodie bag of miscellaneous issues, trading cards, and other swag trembled in my hands. I pulled out an issue I'd brought from home for him to autograph, Batman #492, in which the storyline begun in earnest. I still couldn't afford the back issue one-shot of Chuck Dixon's Vengeance of Bane #1; similarly, I'd missed Dixon's appearance at a Pennsylvania comic store a few months back, though the owner offered to let me have a French fry that he'd touched. I politely declined.

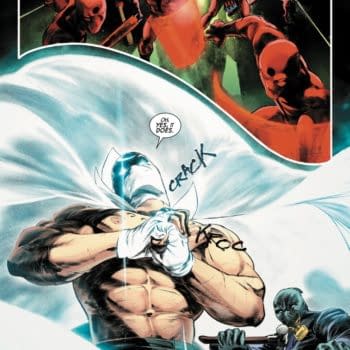

At this time, utterly gripped by the "Knightfall" storyline running through the Batman titles, I was about as excited to meet him as the most ardent Harry Potter fan might've been to meet J.K. Rowling around the release of the penultimate book in the series, or perhaps George R. R. Martin circa now. This, after all, was the man who'd put Batman through psychic and physical ordeals rivaled only by Jim Starlin and Bernie Wrightson's lurid, psychedelic Batman: The Cult, or the grim vistas hinted at in The Dark Knight Returns, which I was only just beginning to, in the spacy sci-fi parlance of some of Moench's strangest, most conspiratorial letters pages, grok.

I probably, in the cliché moment everyone seems to experience in the presence of greatness and/or fame, sputtered out something unintelligible with excitement and glee. Moench didn't look like I expected (but then, what exactly was I expecting?). He looked middle-aged, countercultural, and had rather long hair, a drooping mustache, and wore large-framed glasses. He signed my book, and was certainly nice enough, but didn't say much. He seemed genuinely world-weary and exhausted to me at this age, and probably returned to an endless parade of comics to sign, stacks to plow through, social interactions to move through for a perhaps introverted fellow. With hindsight, I can't say I blame him. He was at the eye of a publicity and hype hurricane, an industry veteran who was watching the world of comics in a strange sort of hyperstasis, right between boom and potential bust, creative renaissance and artistic bankruptcy. It was Shrödinger's medium at this time, and also one poised for a new kind of youth-takeover, with a new crop of adolescent fans seizing onto, and shaping, the violent vigilante antihero embodied by the likes of Azrael, then wearing the mantle of the Bat for a short while. Perhaps, like so many kids these days, they simply missed the point of what Moench et al. were writing.

Conventions, now more than ever, seem to me the domain of youth. While all ages are of course welcome in what at least appears to be a cheerfully inclusive home for geeks of all stripes, geekdom proper now seems a kind of subcultural pageant, perhaps a home for those youth who flocked to punk, gothic, and rave culture in the 1980s and '90s (all three music and subcultural genres, of course, owe some allegiance to comics and animation's visual vocabulary, whether dark and frightening or cheerful, lysergic, and wide-eyed). Youth, both conventional and unconventional attractiveness, and visual boldness are on display in cosplay, inherited from anime fandom: disposable income and the freedom that comes with a childless, unencumbered, and at times chronically underemployed lifestyle. Their enthusiasm truly bubbles over, and my somewhat jaded current mindset envies their joie de vivre. I certainly was young and enthusiastic when I went to conventions, but they predated my desire to subculturally belong. I was also a little frightened, taking in the spectacle, not sure to think, much like I would be at my first VFW hall punk show a few years later.

Some of my first encounters with punk rockers and metalheads were at comic conventions. Among other mental snapshots of my early convention-going days in 1992-1994, I specifically remember seeing tall, intimidating guys with colorful Mohawks and gaudy backpatches striding confidently through the crowd, rifling through back issues with all the rest of the fans. Others had a gloomier disposition and drooping, long hair, often down their backs; I think I also recall young punk women tottering in creepers, heads shaved except for bright forelocks. For the first time, I came face-to-face with people just as colorful and bizarre as the four-color characters we shared an interest in. The cosplay back then was seldom in character, but perhaps involved a more personal invention of self, extending out of the convention hall into high school classrooms, 7-11s and diners late at night, and cluttered bedrooms.

If you've known any old punks or independent music fans, they'll often lecture you about what tracking down obscure records or bands in out-of-the-way venues was like prior to the internet. Some even say that the rise of online culture destroyed the exclusivity and competence-testing of something like punk rock, a haven for outcasts of all stripes. Others, though, welcome the democratic rise of culture. While comic book fans and toy collectors often aren't so harsh in their disdain for how easy the new generation has it—with the horde of obscure cultural offerings now open to all comers—they will talk about how they miss the amount of legwork involved in finding the relics of their passion. I couldn't quite dream of reading comprehensive trade paperback reprints of classic Marvel stories, so I had to be content with Peter Sanderson and Danny Fingeroth's Marvel Saga and 1991's later Spider-Man Saga, an impressively far-reaching "clip show" series that reprinted key moments in Marvel continuity, augmented by text. These were about as good as it got, except for the rare key issue I had saved up enough money to get, or my dad was willing to chip in and split the cost on with me, such as the Claremont/Miller Wolverine limited series. If it'd yet been reprinted as a trade, I certainly wasn't aware of it. Like many of my other convention finds, including the Walt Simonson/Mike Mignola squarebound one-shot epic, Wolverine: The Jungle Adventure, I read and reread them obsessively, thinking about just what it was that made these comics a cut above the rest for me.

Two main features of the convention as a chaotic hall of delights stick out in my memory. The first is the tiered system of longboxes, often stacked atop each other in unwieldy ways, with some of the cheapest—25 cent or less—issues down on the floor, where a pubescent kid could easily crouch down and dig, obsessively, while my dad waited nearby or did some digging of his own. These bins yielded unexpected gold, which I often would buy knowing absolutely nothing about the characters featured therein, but following the lodestone of instinctual enjoyment. I steered clear of New Gods issues due to their possible blasphemous content and parental censure, but was drawn to Detective Comics from the early '80s, often featuring Green Arrow backup stories, Bill Mantlo's Hulk, and the aforementioned Marvel Saga, Secret Wars, and assorted other odds-and-ends titles, like Sgt. Rock, or any squarebound, glossy title, which seemed somehow like the best deal for one's money. I do seem to recall purchasing a polybagged-with-trading-card Mr. T and the T-Force issue from one of these bins, perhaps destined for quarter-bin purgatory from its initial release. This strange, preachy comic wasn't quite something I was ready to laugh at, as I would by the time Mystery Science Theater 3000 truly taught me how to poke fun at pop culture. It made, to say the least, for an inauspicious introduction to the work of Neal Adams.

The other omnipresent feature of this pre-internet assemblage was a series of TV screens and VCRs, broadcasting whatever assorted pop-cultural strangeness was seldom seen in more mainstream outlets. Sometimes, a Star Wars or Star Trek film might be playing in the background as a sort of ambient comfort food, which I still saw happening at toy conventions in the 2000s, while at others it might be playing something like 1984's The Return of Godzilla, such as the booth present at a few cons I'd visited owned by the proprietor of Gelatinous Comics, an intense, ponytailed and bearded hippie sort of fellow who, in passing conversation, took the time to lecture me on his utter disdain for MST3k and its insistent desire to wisecrack all over his beloved Gamera films, which were also subjected to the indignity of being chopped up for commercial breaks.This viewpoint was new to me, and utterly baffling (but considerably more understandable today). I glanced down at an equally perplexing Crumb book that he quickly covered up with both hands, and ended up buying a set of Marx Universal Monsters figures. I think I had wanted a Gamera, but learned that day just how costly the original Japanese vinyl toys really were.

I still have footage from the 1967 Hanna-Barbera Fantastic Four series etched in my brain, Ben Grimm loping along like a gorilla to jazzy soundtrack music, punching boulders in infinite loop, an orange, glum Sisyphus. Other booths played the bizarre, non-linear spectacle of all the possible ways to die in the Don Bluth laserdisc Dragon's Lair arcade game, and a disturbing anime sequence that I was told was not for young eyes, which featured a lot of disturbing sound effects of what sounded like people being drawn and quartered. Before YouTube or even the crude streaming video of RealPlayer, this was the only place to find a repository of such odd cinematic offerings, all for unauthorized sale. I finally bought a DVD of the FF cartoon around 2006, and was disappointed that I'd bought a glitched-out DVD which refused to play over two-thirds of its episodes. You would, and still do, get burned at cons.

Perhaps second only to Doug Moench was M.D. Bright, who had a long run as artist on G.I. Joe, including the "Snake Eyes Trilogy" issues, which were a truly engrossing blockbuster action story that captured my imagination with the same abject grit and pathos of the best Wolverine comics, its existentially depersonalized hero waging a grim battle as he scaled the Cobra Consulate building in search of revenge. Bright, at the time attending the convention perhaps somewhat due to the hype accorded the Green Lantern: Emerald Dawn II series, seemed genuinely pleased to meet an actual young fan, in between dealers who were presenting him with tall stacks of the same issue, undoubtedly to be resold with his signature. I remember that he talked to me for a good long time, and perhaps I was less intimidated than I was by the likes of Moench, taken aback a bit by this man's friendliness and goodwill, seemingly at odds with the sturm und drang of his artwork. I got my issue #95 signed and walked away as excited as could be, having met an actual person who was responsible for the four-color ambrosia of my fantasy world, one that I needed more than ever as I entered junior high school and would be fighting my own battles for survival.

Next time, 1993 brings a new sensibility, a bit ironic and detached, fully appropriate to a young teenager starting to realize how ridiculous superhero comics can sometimes be. Our young hero finds himself the perfect age for Mystery Science Theater 3000, even if he doesn't get 75% of the jokes, and can't tell you why he finds the other 25% funny. He also will be introduced to the work of a certain bearded warlock from Northampton in the unlikely setting of a furniture store, and will finally get around to reading another one-shot written by this man featuring Batman, and his arch-nemesis, doing very grisly things, indeed. Stay tuned…

Christopher Smith teaches composition at Columbus State Community College and has spent about two thirds of his life being obsessed with comics, music, and the strange, somewhat overlooked corners of pop culture. He lives with his wife, son, and two devious cats.