Posted in: Comics | Tagged: art comics, batgirl, Comics, dylan horrocks, entertainment, Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen, spx

SPX '15: Dylan Horrocks On Hicksville, Sam Zabel And The Magic Pen, Batgirl, And Charlie Hebdo

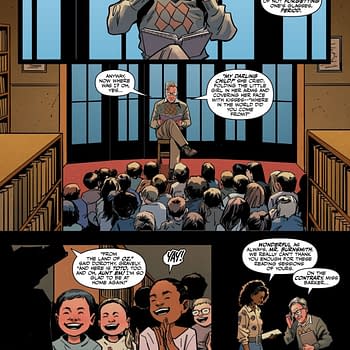

Small Press Expo has lost none of its energy this year—flocked with tables and attendees, and with many panels running throughout the weekend. They welcomed a cartoonist from New Zealand, Dylan Horrocks, who hadn't attended SPX since 1998. His previous works include Hicksville and his new book this year is Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen. His forthcoming book is called Incomplete Works.

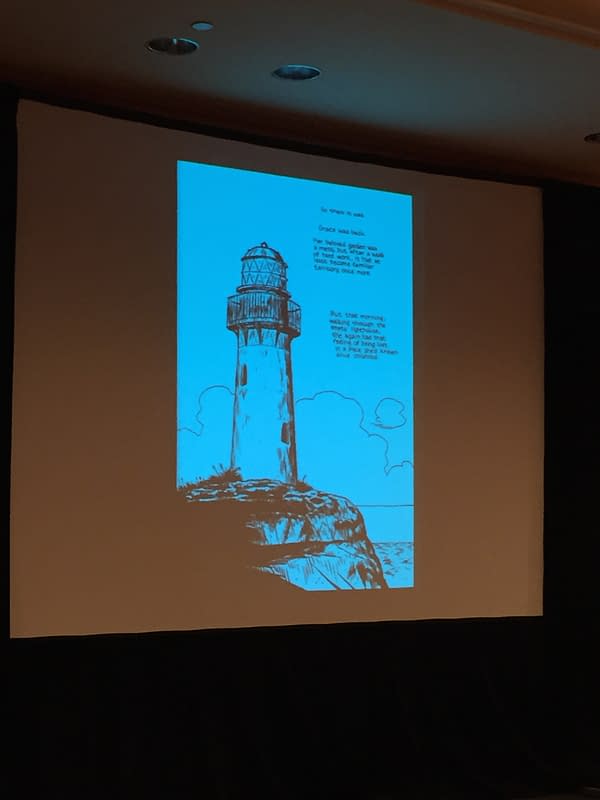

Horrocks explained that Hicksville was "partly about being in love with an artform which is marginal", he said, but also about living in a country "at the utmost bottom of the world that no one takes seriously". It's about staying where you are and "deciding that it is the center of the world". He created a story in which a town is "obsessed with comics" like being at SPX for the weekend, he joked. The lighthouse symbol in the book represents comics for many readers.

Horrocks told a story of Frank Miller reading his work at SPX and paying him a compliment on it. When Hicksville came out, it contained many "common points of reference", Kartalopoul0s said, and so the book speaks to that, but now, to new readers it might feel like "we already live in that world" in terms of the aspirations for the medium.

There's a scene in Hicksville that stays with Horrocks, the final image in the book, where the islands of New Zealand have broken free and are drifting. Three characters are standing on the lighthouse and they see land approaching. He feels like that is exactly what is happening with comics—"a new continent has emerged out of the mist"—and he's so excited to explore it, he said. He doesn't know how young people will read the book now, he admitted, but he's had a lot of novelistic responses from writers. He got invited to literary festivals in New Zealand after the book came out, and the novelists responded to the complexity of "loving any art form and all the compromises and difficulties of being involved in that".

Kartalopoulos commented that you can't walk down the street without noticing something that has saturated culture from comics now, which does resonate with the comics culture of Hicksville. Horrocks added that though the genre is now popular in another medium, the old medium is getting ignored still or increasingly so. So, there is a major difference there.

The love of comics is a major theme in Horrocks' works, but in Sam Zabel, it becomes clear that one of his themes is also artistic crisis. In Zabel, the character has artist's block, for instance. Speaking about a very early work from 1990 called "The Last Fox Story" from his early 20's. In New Zealand, it's a cultural thing for young people to "go OE" for the big Overseas Experience, and he went to England. He thought he would get work in European comics. He ended up working in a bookshop, but he felt a lot of pressure to try to make comics as a career and "as a result I just completely dried up", he said, to the point that going in a comic shop one day gave him a panic attack. He went home and tried to look at ta comic he had been working on and he "just felt sick".

Kartalopoulos said that some people feel alienated by experimental comics, but sometimes that's about "tricking yourself out of the conventions of the form", he said. It can be refreshing to think in comics terms about other fields. Horrocks wrote an essay about Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics that describes a series of paintings as like a comics, for instance. Horrocks confessed that sometimes at the public library, sometimes he's a little disconcerted at how "samey" some graphic novels are becoming in the way they look. A few years ago, there seemed to be a dropping of conventions and a "new feel". Now he sees that as "transitional" and maybe things are different now.

When he had a more recent struggle with comics, reading comics that were less constrained by narrative helped him because it was less like what he had always done, Horrocks said.

Another work that Horrocks developed was Atlas from Drawn and Quarterly, which he eventually decided to discontinue. Kartalopoulos asked how he decided that it was time to stop the project. It was published during a time when Horrocks was feeling pressure because of the success of Hicksville and felt he was expected to produce a "literary masterpiece in comics form". He does hope to finish it someday, but felt it was very hard to do a good book because he was "looking over his own shoulder" too much. It was "crippling" to try to meet that demand. He got "tangled up".

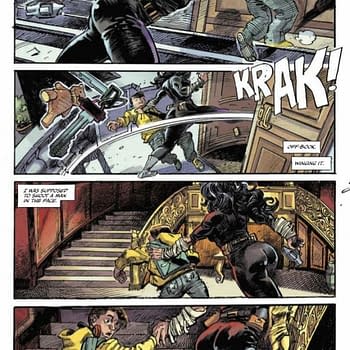

Around the same time, he got hired by DC Comics to writer Hunter: The Age of Magic for Vertigo, and then wrote Batgirl for a year and a half. He did it for 4 years in total, but he discovered that he can't write commercial comics. It was financially helpful for him as well as socially helpful since people had heard of the characters he was working on. Superhero comics are not a fantasy that's his fantasy, he decided. By the end of the experience, he was very burned out and found it difficult to write or draw anything. "I'd almost lost my faith in stories", he confessed. Even movies and fictional novels seemed too "contrived". He became obsessed with a quote from Picasso that "Art is a lie that tells the truth" and worried that art might just be a lie about the world. He was depressed and "a mess" during that time, which ground Atlas to a halt. He didn't trust stories or art anymore, Horrocks said. A religious friend who had lost his faith told him that what he was going through was a "crisis of faith". Magic Pen was the result of this experience, he explained.

Kartalopoulos brought up Charlie Hebdo and the question of moral responsibility for art, and Horrocks said that in the English-speaking world the commentary that arose was based on people having no idea about what Charlie Hebdo really was or who the cartoonists were. He was frustrated by the way in which arguments would play out in which both sides were not knowledgeable. Some considered it a virtue not to know and just look at the images to interpret them, and he felt like there was a big problem with that approach. Since political cartoons are "deeply embedded in context". In the course of this discussion, his own relationship to the Magic Pen book changed as a conversation with himself based on this question of responsibility.

It also harked back to his "uneasiness" writing some of the Batgirl stories which focused on "violent predators" where the only way to protect the innocent was to become even more violent than them. One of the issues he wrote has a recruiting ad for the US Army and it seemed to present the same narrative about the world. To be tougher than a predatory world. Charlie Hebdo massacre made "very immediate" for him the other side of the argument—the ability to draw freely, and avoid self-censorship too. For a magazine recently, Horrocks did a "page work" researching cartoonists who have been tortured or killed for drawing comics. He placed 27 on a page, but it was "just the tip of the iceberg" and from all over the world. Many faiths, political viewpoints, and more were represented, but simply drawing caused harm to them.

The "stakes are high", Horrocks said, and it's important we "don't forget". If we start to "embrace censorship and suppression", we open ourselves up this kind of danger, he said. Trying to "purify" culture to represent only those things that you approve of, even if driven by good intentions to remove destructive elements can lead us into the same trap as the Nazis pursued in seeking to control art, he concluded.