Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: Boy Commandos, human torch, Master Comics, Promise Collection

The Promise Collection 1941/1942: Comics Go to War

"A market of some twenty odd publishers getting out over a hundred different magazines using nearly 2,000,000 words of copy a month is big time," explained an October, 1941 Writer's Digest article titled The Comics are Calling. "This new market needs you and you need it — and that's no popular soft drink slogan. The comics have been going through a similar metamorphosis to what the pulps did a few years back. Only more swiftly. At first comic book artists did their own stories and anything went. But the novelty of poor stories told in picture form wore off for the young (and many not so young) readers. Publishers held war councils, made analyses of their competitor's products and came to their senses. The whole field improved… Professionals in other writing fields were loath to leave their lush literary pastures for a new, untried and at the time, poorly-paying medium. So entered a group of local lads who were amateur writers but professional opportunists… They were accepted in desperation by comic book editors. A few legitimate pulpsters and true-crime detective scribes did manage to ease in and give out with such vastly superior material that they struck a bonanza. Some of them will call me nasty names for giving the deal away. But it had to come out eventually. All writers need competition. It makes us write better stuff. Which in turn makes the magazines better and builds up the market."

Writer's Digest was certainly correct about the expanding market. There were roughly 750 comics on the American newsstand in 1940, about 950 comics in 1941, and nearly 1200 comics in 1942. And the Promise Collection was expanding even more dramatically over this period. The collection which starts with just a single comic book cover-dated 1939, would expand by 15 comics in 1940, 55 comics in 1941, and 93 comics in 1942. Over this period, comics would learn a lesson that comic book characters have been reenacting ever since: a superhero's intentions are easily misunderstood, and when that happens… chaos ensues. Comic books would fight battles on multiple fronts during this time.

Welcome to Part 4 of the Promise Collection series, which is meant to serve as liner notes of sorts for the comic books in the collection. The Promise Collection is a set of nearly 5,000 comic books, 95% of which are blisteringly high grade, that were published from 1939 to 1952 and purchased by one young comic book fan. The name of the Promise Collection was inspired by the reason that it was saved and kept in such amazing condition since that time. An avid comic book fan named Junie and his older brother Robert went to war in Korea. Robert Promised Junie that he would take care of his brother's beloved comic book collection should anything happen to him. Junie was killed during the Korean War, and Robert kept his promise. There are more details about that background in a previous post regarding this incredible collection of comic books. And over the course of a few dozen articles in this new series of posts, we will also be revealing the complete listing of the collection. You can always catch up with posts about this collection at this link, which will become a hub of sorts regarding these comic books over time.

The People vs The Batman

"Virtually every child in America is reading color 'comic' magazines — a poisonous mushroom growth of the last two years. Ten million copies of these sex-horror serials are sold every month. One million dollars are taken from the pockets of America's children. Save for a scattering of more or less innocuous 'gag' comics and some reprints of newspaper strips, we found that the bulk of these lurid publications depend for their appeal upon mayhem, murder, torture and abduction — often with a child as the victim. Superman heroics, voluptuous females in scanty attire, blazing machine guns, hooded 'justice' and cheap political propaganda were to be found on almost every page," wrote Sterling North in a May 8, 1940 editorial in the Chicago Daily News, which would somewhat infamously become an opening salvo of sorts for the criticism of the early era of the Golden Age of comic books. And while there are a scant few truths in North's missive — Superman heroics, hooded justice, and yes, even political propaganda are easy to find in the comics of this and many eras — his attack is so overheated that it seems hard to believe it was taken seriously, even in 1940. He concludes his editorial by accusing teachers who find educational value in comic books guilty of "cultural slaughter of the innocents" and parents who allow their children to read comic books guilty of criminal negligence. A little background on North provides some additional perspective on his views — the story of his apparently idyllic childhood was turned into a Disney movie, (another of North's books also became a Disney movie) and a later critic of his writing would note, "I guess what moves Sterling North to write and his wide audience to read him . . . is nostalgia for a past when the struggle was with virgin lands and not with an environment corrupted by man."

Nevertheless, over the next year, the jarring staccato shocks of criticism from Sterling North and a handful of others would become a more regular background drumbeat for the rising comic book industry. Even newspaper comic strips were feeling the blowback from the perceived reputation of comic books. "These letters have been more numerous of late than at any time in my 30 years as a newspaperman. They are sufficiently numerous to be straws in the wind indicating what seems to be growing public sentiment. I think newspaper comics are to a considerable degree innocent victims of parental resentment created by the comic books — some of which go much farther in the matters of horror or sex than any newspaper has ever gone," explained a column in Editor and Publisher in early 1941.

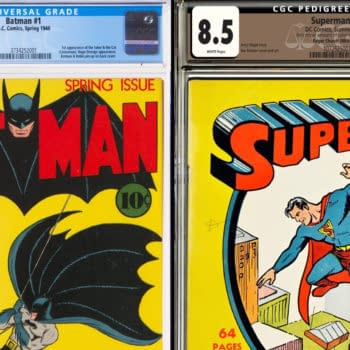

The Promise Collection's run of Batman continues unbroken throughout 1941 and beyond, and a story in Batman #7 called The People vs The Batman almost seems like a direct response to such growing anti-comics sentiments. When Batman's intentions are misunderstood, he is arrested and stands accused of misdeeds in court. Coming to his defense, Commissioner Gordon tells the jury, "This man who has saved a nation's gold reserve, fought fifth columnists and saboteurs, beaten the Joker, the Puppet Master, and other crime geniuses… this man who daily risks his life to save others, who never carries a gun, fights crime with the courage and zeal born of love for his fellow man." Gordon even addresses the vigilante aspect of the character with, "From now on, you work hand in hand with the police!"

Captain America Comics throughout this period made a concerted effort to have a constructive impact on its readers in a different way, and the Promise Collection's run of the title likewise remains unbroken through this period. The now-famous Sentinels of Liberty club, with its membership card, official badge, and solemn pledge to "uphold the principles of the Sentinels of Liberty and assist Captain America in his war against spies in the U.S.A." began to put specific actions behind that pledge as 1941 progressed. The week that Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill signed the Atlantic Charter, Captain America Comics #7 was on the stands with Captain America declaring a "State of Unlimited Junior National Emergency" for the Sentinels of Liberty. And with tensions heightening that September after the USS Greer became the first U.S.warship fired upon by a German U-boat, Captain America Comics #9 instructed club members to "make note of every plane you see in the sky… Then, in the event of an aerial attack, you Sentinels will be able to do your share in spotting enemy planes and warning the authorities."

Freedom, Democracy and Womankind

Like its run of Batman, the Promise Collection's run of Detective Comics also continues unbroken through this 1941 / early 1942 period, and if Batman #7 seemed like a veiled response to some public perceptions about comic books of the time, then Detective Comics #58 (and other DC Comics cover-dated October 1941) was a direct shot at both the sentiments expressed by Sterling North and other critics and the quality issues noted by Writer's Digest. In a message to readers on the inside from cover, DC Comics introduced their editorial advisory board: "Since the inception of this and other DC magazines, a rigid policy has guided the editors in their selection and presentation of editorial material. A deep respect for our obligation to the young people of America and their parents and our responsibility as parents ourselves combine to set our standards of wholesome entertainment. Early this year we recognized the value of active assistance on the part of those professional men and women who have made a life work of child psychology, education and welfare. As a result we secured the collaboration of five Advisory Editors, each a leader in his or her respective field."

The Advisory Board consisted of Dr. Robert Thorndike of Columbia University, Ruth Eastwood Perl of the American Psychological Association, former World's Heavyweight Boxing Champion and then-current Lieutenant Commander in charge of the U.S. Navy's Physical Fitness Program Gene Tunney, Dr. C. Bowie Millican of New York University, and Josette Frank of the Child Study Association of America. Another editorial on the inside front cover of Detective Comics #59 (among other issues that month) noted the addition of the most historically interesting of the editorial advisors: William Moulton Marston. Best known to history as the co-creator of Wonder Woman, his connection to the character would not be made public at this time, even though the editorial introducing him to the Advisory Board also appeared on the inside front cover of Wonder Woman's first appearance in All-Star Comics #8.

The creation of the Advisory Board by DC Comics was in large measure a marketing move that would loosely tie into the introduction of Wonder Woman throughout this late 1941 / early 1942 period. Josette Frank had already become a public advocate for comic books by this time, as had William Moulton Marston. When DC's All-American Comics branch added Alice Marble as an associate editor on Wonder Woman in 1942, she too would become a public advocate for comics. Marble, at that time perhaps the most famous female athlete in the country with 18 Grand Slam tennis championships to her credit and the US women's #1 ranked player from 1936 to 1940, would also play a crucial role in the marketing roll-out of Wonder Woman as a character. Sensation Comics #1 would play a key part in that rollout, and that issue is one of the major keys from this time frame that is part of the Promise Collection.

Hitting the newsstand about 2 weeks after Wonder Woman's first appearance in All Star Comics #8, Sensation Comics #1 is an important and sometimes overlooked key. It continues the origin story from All-Star Comics #8, introduces the invisible jet, and brings Wonder Woman to "Man's World" in her secret identity as nurse Diana Prince. This anthology comic also includes stories that introduce long-lived DC Comics characters Wildcat and Mr. Terrific. And as we know from marketing materials distributed using Alice Marble's name and star-power, Sensation Comics #1 was a key part of the debut of the character. Notably, Marston is also unveiled in this marketing as the creator of the character and as the "famous Harvard psychologist and inventor of the widely-publicized lie detector". The effort in these materials to promote Wonder Woman as the female counterpart of Superman is likewise interesting and includes a version of the "Faster than a speeding bullet" phrasing made famous by the syndicated Superman radio show just a year prior to this. Wonder Woman's version of the blurb says, "She can leap through the air with the speed of a bullet, lift tons of weight, withstand high electric voltage, read the thoughts of others by mental radio."

The marketing materials further note that Wonder Woman had appeared as one of eight stories in Sensation Comics and was selected by reader poll — "80% chose Wonder Woman as their favorite over seven male characters." This seems to be another attempt to parallel Superman, as the high-profile Saturday Evening Post piece from June 1941 on the rise of "Superman, Inc" which we referenced last week in this Promise Collection series contains an anecdote from DC Comics owner Harry Donenfeld stating that Superman was also chosen as the favorite by reader poll (which appears in Action Comics #4). However, the notion that Wonder Woman received her own series due to overwhelming popularity in a Sensation Comics reader poll appears to be a polite marketing fiction. A succession of popular sports stars of the day — Jack Dempsy, DC Comics Advisory Board member Gene Tunney, and finally Alice Marble herself — have written endorsements of Wonder Woman that appear in successive issues of All-Star Comics, which culminates in the poll in Sensation Comics #5 asking readers to send in their choice for favorite of the Sensation characters — and receive a Wonder Woman button as a thank you. But Max Gaines filed the Wonder Woman logo with the US Patent and Trademark Office long before the reader vote, and even a week prior to that Saturday Evening Post article on Superman. If they were about to tell the world exactly how successful Superman had become (the article contains moments of candor about exactly how much money DC's owners were making from Superman which seem remarkable in light of subsequent events), I imagine they wanted to start laying the groundwork for a super woman.

Sensation Comics #1 itself ties Wonder Woman into what would soon become America's war effort, by explaining that the character fights for America due to U.S. Army Intelligence Officer Steve Trevor's arrival on Paradise Island, which prompted her to "bring him back to America and help him wage battle for freedom, democracy, and womankind throughout the world." A quoted passage from Marston in the Wonder Woman promotional materials completes this picture: "It is highly significant to a psychologist that Hitler and his original gang of political racketeers were singularly free from the influence of women. There was no woman's influence whatsoever in the emotional beginnings of Nazism. The result, inevitably, was unrestrained male dominance. There's no more reason for not killing humans who oppose you than for sparing the lives of mosquitoes, in the mind of a man whose self-seeking emotions are permitted to run rampant. And the average 'normal' males personality balance tends definitely in the same direction, according to the emotions tests which I have conducted for several years."

Heroes and Young Allies in the Promise Collection

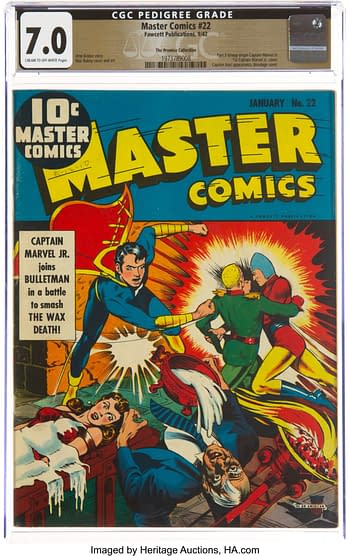

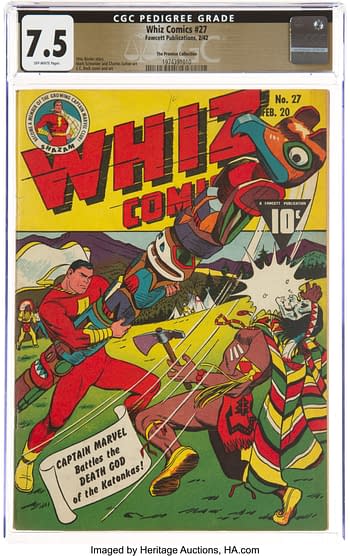

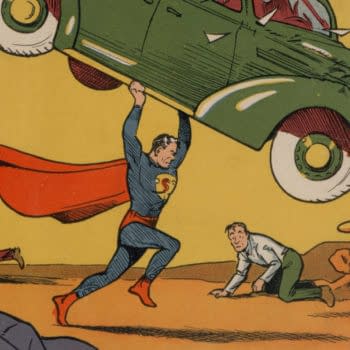

The United States declared War on Japan on December 8, 1941 in the wake of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and responded in kind to Germany and Italy's subsequent declaration of war on December 11, 1941. But by the Fall of that year, the media and public sentiment had begun to view America's entry into the war as inevitable, and so had comic books. The comic book heroes' battles against saboteurs and fifth columnists had steadily turned into more direct action. In one of the most memorable storylines of the era, Captain Marvel, Bulletman, and Captain Marvel Jr. take part in an epic battle against a character called Captain Nazi, who had been ordered by Hitler to take America's heroes down. This battle played out through Master Comics #21, Whiz Comics #25 and Master Comics #22 — all of which are present in the Promise Collection from this period.

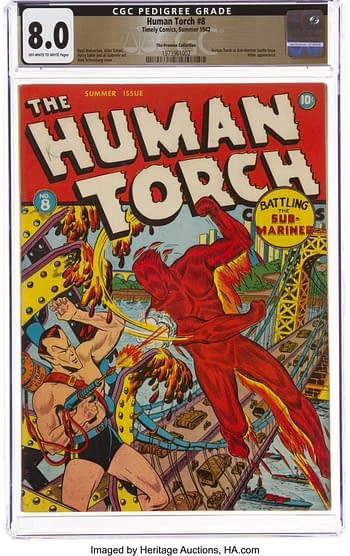

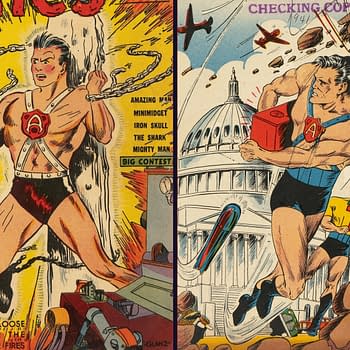

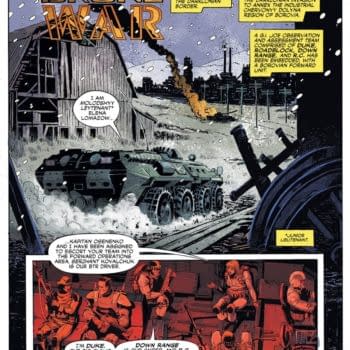

America's formal declaration of war did change things for comics, as superheroes fighting the war on a number of fronts quickly became the norm. Supervillains attacking America under Hitler's orders would also become a matter of routine in the comics of early 1942, as we can see in issues ranging from Pep Comics #30 to Human Torch #8. That Human Torch issue is another classic knock-down, drag-out battle in which the Human Torch and the Sub-Mariner set aside their differences to take on Hitler's villain, the Python. A text story called "The Men Hitler Fears" explains that Hitler intended to invade America and Capture New York City. Smash Comics #34 saw the Ray taking the fight against Nazis to occupied Budapest, while the debut of Joe Simon and Jack Kirby's Boy Commandos in Detective Comics #64 dropped the boy soldiers directly into the action in occupied France. Young Allies #3, which hit the newsstands in mid-March 1942, got directly to the point on its cover: "Remember Pearl Harbor."

But comic book history's most under-discussed challenge also loomed in those early moments of 1942. As one paper explained that February, "Among the sub-agencies planned in Washington is a Bureau of Comic Book Propaganda." Later in the year, another paper noted "The WPB [War Production Board], motivated by a very biased advisory board, is seriously considering ordering the discontinuance of magazines such as motion picture fan magazines, pulp paper magazines, children's comic magazines, etc… Recently, the head of a rationing board in Sheboygan, Wis., refused to give a wholesale distributor a certificate for two tires, unless the distributor discontinued placing on sale certain magazines which this rationing board member did not like." In the next installment of the Promise Collection series, we'll dive headfirst into how the Office of Wartime Information's Writers' War Board and its "sub-agency" the Comics Committee dramatically changed the face of comics in late 1942 and beyond.

| Comic Title | Issue # | CGC Grade / Auction Links | Prices Realized |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-Winners Comics | 5 | ||

| America's Greatest Comics | 1 | ||

| America's Greatest Comics | 2 | ||

| America's Greatest Comics | 3 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 6 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 7 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 8 | ||

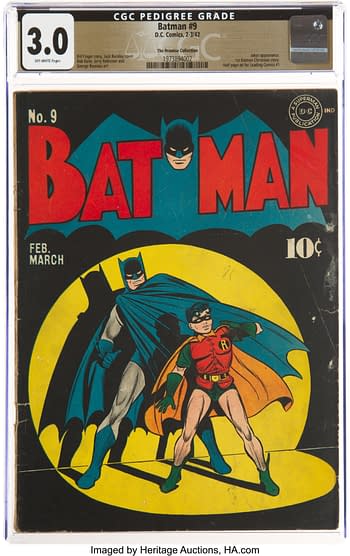

| Batman (1940) | 9 | Batman #9 CGC GD/VG 3.0 Off-white pages | $3,600.00 |

| Batman (1940) | 10 | ||

| Batman (1940) | 11 | ||

| Bulletman | 2 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 7 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 8 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 9 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 10 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 11 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 12 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 13 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 14 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 15 | ||

| Captain America Comics | 16 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 6 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 7 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 8 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 9 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 10 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 11 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 12 | ||

| Captain Marvel Adventures | 13 | ||

| Catman Comics | 1 | ||

| Catman Comics | 2 | ||

| Daredevil Comics (1941) | 9 | ||

| Detective Comics | 56 | ||

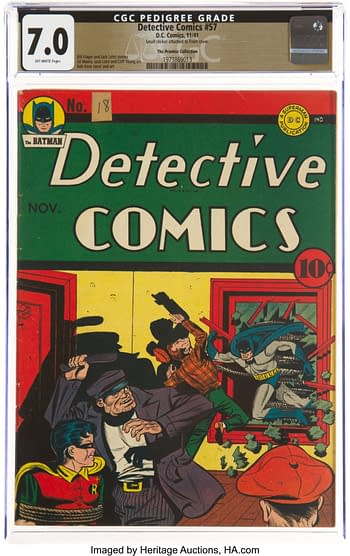

| Detective Comics | 57 | Detective Comics #57 CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages | |

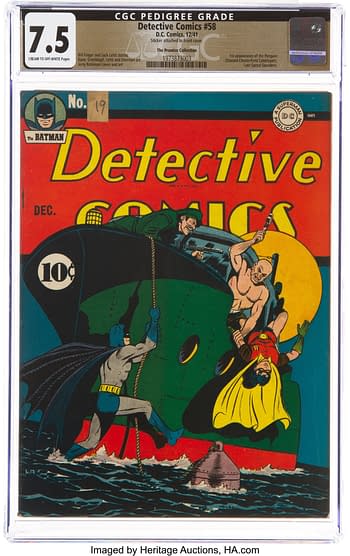

| Detective Comics | 58 | Detective Comics #58 CGC VF- 7.5 Cream to off-white pages | |

| Detective Comics | 59 | ||

| Detective Comics | 60 | ||

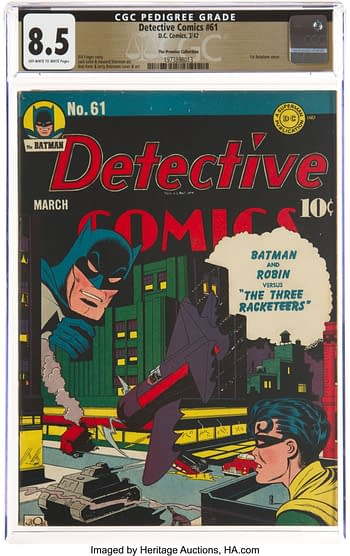

| Detective Comics | 61 | Detective Comics #61 CGC VF+ 8.5 Off-white to white pages | |

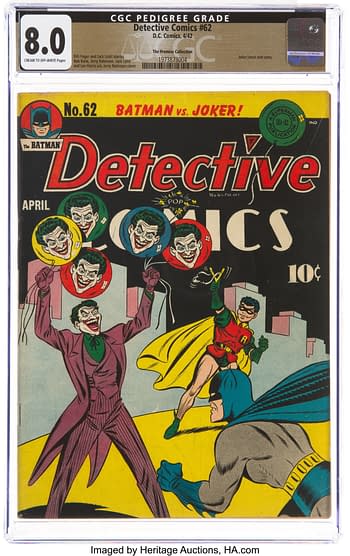

| Detective Comics | 62 | Detective Comics #62 CGC VF 8.0 Cream to off-white pages | |

| Detective Comics | 63 | Detective Comics #63 CGC FN+ 6.5 Off-white to white pages | $3,120.00 |

| Detective Comics | 64 | ||

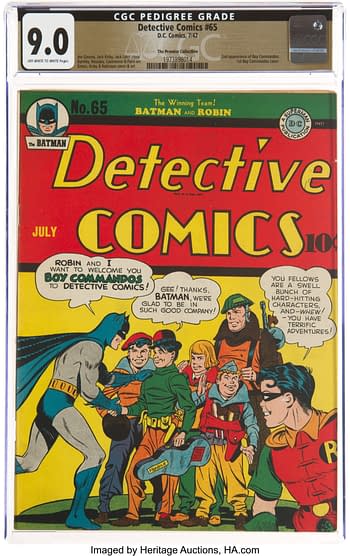

| Detective Comics | 65 | Detective Comics #65 CGC VF/NM 9.0 Off-white to white pages | |

| Human Torch | 8 | The Human Torch #8 CGC VF 8.0 Off-white to white pages | |

| Master Comics | 21 | ||

| Master Comics | 22 | Master Comics #22 CGC FN/VF 7.0 Cream to off-white pages | |

| Master Comics | 27 | ||

| Pep Comics | 29 | ||

| Sensation Comics | 1 | ||

| Smash Comics | 34 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 22 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 23 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 24 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 25 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 26 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 27 | Whiz Comics #27 CGC VF- 7.5 Off-white pages | |

| Whiz Comics | 28 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 29 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 30 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 31 | ||

| Whiz Comics | 32 | ||

| World's Finest Comics | 3 | ||

| World's Finest Comics | 4 | ||

| World's Finest Comics | 5 | ||

| World's Finest Comics | 6 | ||

| Young Allies | 3 | ||

| Young Allies | 4 |

- Batman #9 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC GD/VG 3.0 Off-white pages

- Detective Comics #57 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1941) CGC FN/VF 7.0 Off-white pages

- Detective Comics #58 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1941) CGC VF- 7.5 Cream to off-white pages

- Detective Comics #61 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC VF+ 8.5 Off-white to white pages

- Detective Comics #62 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC VF 8.0 Cream to off-white pages

- Detective Comics #65 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC VF/NM 9.0 Off-white to white pages

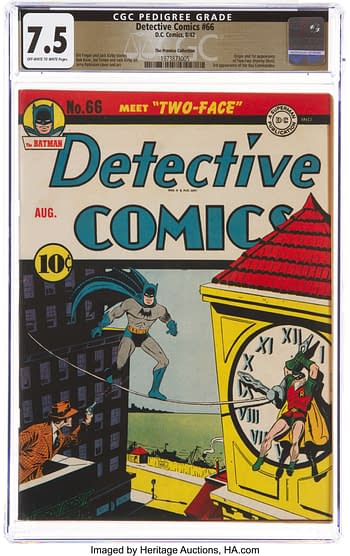

- Detective Comics #66 The Promise Collection Pedigree (DC, 1942) CGC VF- 7.5 Off-white to white pages

- The Human Torch #8 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Timely, 1942) CGC VF 8.0 Off-white to white pages

- Master Comics #22 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Fawcett Publications, 1942) CGC FN/VF 7.0 Cream to off-white pages

- Whiz Comics #27 The Promise Collection Pedigree (Fawcett Publications, 1942) CGC VF- 7.5 Off-white pages