Posted in: Batman, Comics, DC Comics, Recent Updates, Vintage Paper | Tagged: Batman, bill finger, joker, laughing fiend

Batman 1839, Part 1: Mad Men of Gotham

Indeed the materials are so profuse that the author who deals in them requires neither invention nor imagination, but merely a fair talent for telling the truth takingly, for once he begins, he will find it scattered about him in rich confusion, any quantity of the prettiest and most interesting little loves — murders — intrigues — sentimental suicides — broken hearts — secret associations — forced marriages — mysterious orphans — curious coincidences — midnight strangers muffled up in dark cloaks, and looking suggestive of Spanish stilettos — nay even of duels, conspiracies, and ghosts — that ever threw a blotter of white paper into a rhapsody, or astounded and captivated the reading public.

Our opening quote is a description of Gotham, aimed at authors of fiction. It's from an 1842 edition of Brother Jonathan, and I think that it's so nice, that I've used it twice. I'd originally been searching for the background elements that lead to the publication of the first comic book in America, and was surprised to find such a perfect description of a raucously thriving city that had made the leap from the stark reality of New York City, to the dreams and nightmares of fictional Gotham.

I was a little taken aback to find this passage, wrapped up in its dark cloaks worn by midnight strangers, and so directly on point that it could've been written twenty minutes ago rather than closer to two centuries ago — but I shouldn't have been surprised. I went looking for the beginnings of a fictional medium that America made its own, and found America's fictional heart in the process.

But before I get too wrapped up in that, this is supposed to be an introduction.

"Batman 1839" is a series of posts that take a deep dive into something I've discovered which I think is a significant influence on Bill Finger's development of the Batman mythos. It's a thread of historical events that I stumbled across, thought it might mean something, and started tracing back through time. And just when I realized that it was all too much to be a coincidence, I found the historical smoking gun: one of Bill Finger's ancestors, the first Finger to live in America in fact, is connected to all of it.

Johannes Finger (he spelled it 'Vinger' originally, I'm going to refer to him as Johannes Finger for the sake of clarity) was a tenant on the property of a very large manor in New York. This manor has some little-known caves underneath it. And that's just a tiny part of this astonishing story of US history, which I've tracked through several decades before the American Revolution, to several decades after that in New York State — as I think Bill Finger must have done before me, in 1939 and beyond.

Significant parts of the Batman mythos are strongly influenced by the history of New York. And Batman's greatest villain has roots in a real-life figure who might just be the biggest wildcard in American history.

All Manner of Fish and Flesh

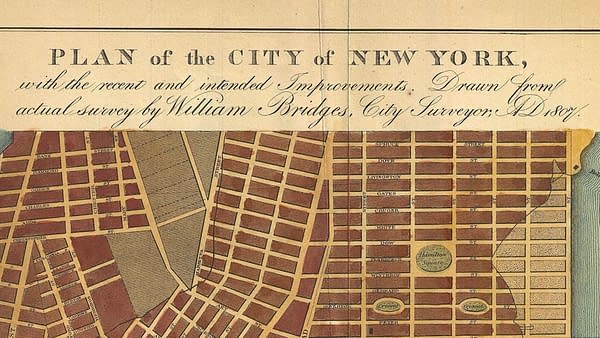

It's fairly well known that author Washington Irving first applied the name "Gotham" to New York City in his literary magazine Salmagundi, published in 1807. Irving set about building up a fictional image of Gotham that was "possessed of mighty treasures, abound with all manner of fish and flesh, and eatables and drinkables" and as such, was looked upon as a target by men with villainous intent.

This work of Irving's is satire, but the picture it paints is valid. New York City had undergone dramatic changes over the preceding decades and had developed into the country's center of commerce. The British had withdrawn from the city 24 years prior to Irving's vantage point in 1807 — and the city, the whole country, was now bracing for their return. But even as they made preparations for another war, things were booming in New York City. Plans for expansion were being made. Robert Fulton had just shocked the city and the entire state by deploying his first viable steamboat and making the round trip from New York City to Albany in less than one third the time that it took for sailing sloops to make the trip (the family of Fulton's financial patron owned the manor where Johannes Finger had lived, uncoincidentally enough). The atmosphere of the moment was both dangerous and breathtaking. That's Gotham for you.

Nobody ever has to tell you about Gotham, it's something you just absorb. It's always been there, since colonial times — a weird city with a weird history and legends grown up out of the tangled branches of its Dutch and British roots. It's a place that operates by its own set of laws — quite literally, as we shall soon see.

There was even a Gotham before this one, and Irving knew this and made the connection deliberately. Irving did a lot of this kind of thing throughout his work, blending fiction, real history, and satire in a way that seemed to be an attempt at creating centuries-old historical legend that the young country didn't really have, quite yet. As we'll see, a fair bit of Irving's work is directly on point in addressing the historical circumstances that made Gotham the place that we know it to be.

But this earlier Gotham also loomed large in its fictional legend in its day, and had its own mysterious champion of the downtrodden. A historian of this prior Gotham says that the name is a derivation of Gataham or Gatham. Put simply, a dwelling place of goats. It then progressed to Goteham, then Gotam, and finally, by the early 14th century… Gotham.

I'm reading a book about the history of this Gotham and the Merry Tales of the Mad Men of Gotham, and some earlier tales of Wise Men, that made it famous a few centuries ago. The author of this history begins, from his perspective in the year 1900, by noting that:

The present generation can have no conception of how universally the tradition of the men of Gotham was known, quoted, and jested with, in bygone England. Indeed, it may be said that the tradition is only just beginning to be forgotten.

History has shown him right about that. I'm told that Warner Bros sometimes holds Batman-related events in this other Gotham due to the novelty of the name, but I doubt they realize just how closely it ties into the ongoing storyline which they've been publishing for nearly 80 years now.

The author that history of this other Gotham also notes that in examining such history, what we see is "only scraps of the whole story — a mere wreckage, shreds and threads of a once continuous pattern — detached tesserae from a once complete mosaic".

Nailed it. He has me at hello. And I was halfway through the book when I guessed his ending. He concludes:

Early in the 19th century there transpired a parallel literary circumstance to some of those just noticed, but with the conspicuous difference that the name was in this memorable instance applied by a future eminent writer of the New World to the greatest city of the other hemisphere.

Parallel literary circumstances indeed. He's making a call-back to Washington Irving there, and to put it in modern comic book terms, he's also talking about what Irving has done as a literary multiverse, created by different writers in different eras, interpreting very similar underlying events — and perhaps even similar underlying characters.

The old Gotham is in the vicinity of Nottingham, and the Merry Tales of the Mad Men of Gotham reference the mysterious hero who rose up to address the wrongs of his era: Robin Hood.

But did the Gotham of the New World have such a hero as well?

A Town Called Vanity

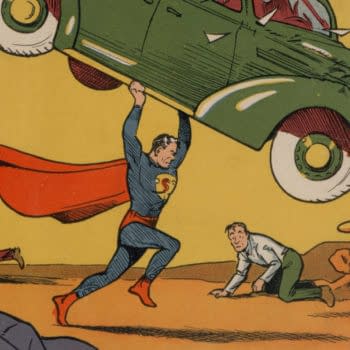

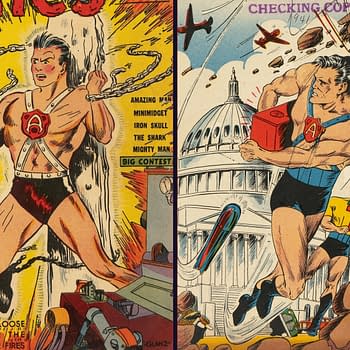

If your grandparents or great-grandparents were born here or lived most of their lives here, they lived during a time when it was not uncommon for costumed vigilantes of a wide variety of aims and goals to put on masks to conceal their identities, use code names for similar reasons, and take the law into their own hands for purposes they felt were important. Such vigilante groups operated throughout the country, and made national headlines on a regular basis.

It's a thing we seem to have erased from our collective memories. That might be because one particular group that started during the 19th century, the KKK, has overshadowed the historical discussion on the issue. But there were very many groups, which formed all over the country for a variety of reasons. Many groups formed to protect an area from local outlaws, when they believed law enforcement to be inadequate. But there were many other reasons, along political, social, and economic lines. The concept was so common for a few decades in the late 19th century that you might not believe it. It's not something that shows up too much in school history texts.

But I'm going to keep throwing links at you until you do believe it. Because it's an important concept that has everything in the world to do with American comic books, and what makes them what they are today.

All of that is preamble to something very simple. It started with a single drawing.

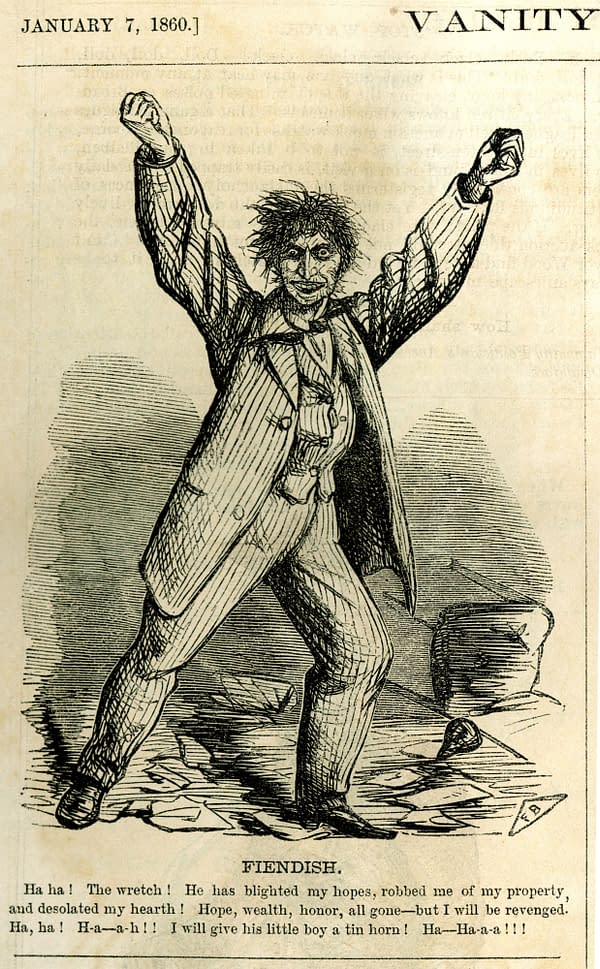

This all began a few weeks ago when I scanning a few pages from the first year's worth of comic paper Vanity Fair, which was launched in 1859. There have been several versions of Vanity Fair since that first one, but the original was essentially an American version of the British comic paper Punch — which is to say it has lots of comics and illustrations, and is basically a satirical take on the news. Which makes it kind of like an 1859 version of The Daily Show I suppose, except it was weekly.

The debut issue explains the title, and in case you ever wondered about that it's exactly what you'd expect: you know what those two words mean separately, put them together and the result is precisely what they intended. They explain that they got that concept from the book The Pilgrim's Progress, a 1678 publication which was at that time the #2 all-time bestselling English language book in the world.

In The Pilgrim's Progress, Vanity Fair is described kind of like a never-ending comicon, except that it's a never-ending comicon held in Hell. Pretty much. And maybe you go there hoping to score a Detective Comics #168, but before you find one you blow all your money on variant covers or something like that.

Point being, it's a clever name for a comics-oriented magazine.

I read a hell of an anecdote recently involving Vanity Fair, Abraham Lincoln, and the Emancipation Proclamation that I'm going to research soon and tell you all about it, if it pans out. Vanity Fair certainly wasn't the only comic weekly in the country at that time, but it was an interesting one, with an interesting approach, and it was starting at a critical time in the country's history. Lincoln would be elected in a few months, and shortly after that came the Civil War. As I was flipping through the pages of this history recently, I spotted something that I hadn't seen before.

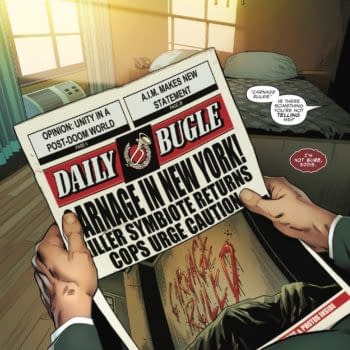

I've taken to calling this character the Laughing Fiend, for the content of the text caption below the drawn figure. The art is by the great Frank Bellew, one of the most important comic artists of this era. Obviously, this is a very Joker-looking character, complete with maniac grin and maniacal laughter in his caption, and there must have been some specific, then-recent news incident that he's based upon, because that's how this worked at the time — they were giving a satirical take on something sensational or shocking that just happened.

I now know who the Laughing Fiend is, and I know exactly how he connects to the Joker, and that's very cool but it isn't even the best part.

Because as I set about searching for the identity of the true-life figure who inspired the Laughing Fiend, I found something else entirely in the historical time and place that I expected to find him.

I knew I was onto something interesting, well before I identified the Laughing Fiend. Because, essentially, I'd gone looking for the Joker… and found Batman instead.

Coming Next: Part 2 of Batman 1839 — The Masked Vigilantes That Changed America.