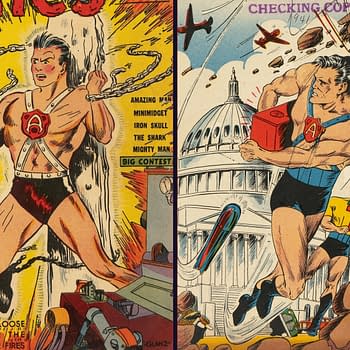

Posted in: Comics, Vintage Paper | Tagged: blue beetle, cat-man, holyoke, iron man, ned buntline, republican party, samuel bowles III, sherman bowles

How A Comic Book Publisher's Family Helped Start the Republican Party

But there's a lot of history behind the Holyoke name — and also behind the Bowles family name — which I find intriguing because it does one of my favorite things: it combines comics history with the larger fabric of American history.

A Comic Book Publisher in the Paper City

Holyoke, Massachusetts was for a period in the mid to late 19th century the largest source of paper in the United States, with several major paper mills located there. It became known as "The Paper City". Holyoke is situated on the Connecticut River, in the Middle Connecticut River Valley. In his book The Story of Holyoke, local historian Wyatt E. Harper explained how the forces of commerce, technology, and nature converged on the area around 1845 to make Holyoke one of the country's early centers of manufacturing. A traveling businessman from Vermont named George C. Ewing, having noted what had been done in Lowell, Massachusetts already by harnessing the Merrimack River, imagined something even bigger for Holyoke:

Here was power on such a stupendous scale as the world had never seen harnessed before. It was said that the river coming to the edge of a strata of shale dropped downward in the valley for a distance of sixty-five feet in less than two miles. The greater part of the rapids was included within an interval of five or six hundred yards.

What man had done on a lesser scale, man could do in a bigger way. Ewing lived in a transcendental age; onward and upward, bigger and better. His vision encompassed the construction of a dam to harness the river completely and compel it to give up its awesome power to the service of man.

The first paper manufacturer to establish itself in Holyoke and harness this power was the Parsons Paper Company in 1853. Due to technological advances in printing and the development of a national distribution network with the American News Company by Sinclair Tousey just after the Civil War, the need for paper in the United States soon exploded. Within 20 years, there were 14 paper mills in Holyoke, producing 40 tons of paper per day. By 1890 the number of paper mills in Holyoke had increased to 25, employing 3,500 people. Holyoke had become the Paper City.

Naturally, such a nucleus of paper manufacture also lead to printing and publishing infrastructure developing there as well. And Sherman Bowles came to own a particularly fascinating bit of publishing infrastructure there indeed, which even I would have to admit… the comics publishing part of that legacy is fairly far down the list on its contributions to American publishing history.

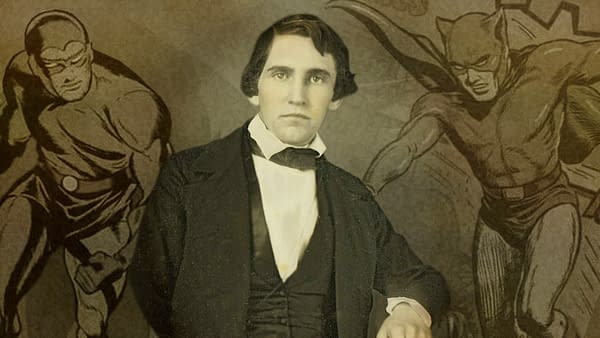

Sherman Bowles' great-grandfather Samuel Bowles III helped to give the Republican Party its name, and was one of the party's most influential voices from its earliest days.

Statesmen and Submariners

The origin moments of the Republican Party are usually simply alluded to by calling it "The Party of Lincoln." While that's certainly true, it might be more precise to note that the party's true origins eventually led directly to Abraham Lincoln's moment in history. In the modern day, GOP.com notes:

On July 6, 1854, just after the anniversary of the nation, an anti-slavery state convention was held in Jackson, Michigan. The hot day forced the large crowd outside to a nearby oak grove. At this "Under the Oaks Convention" the first statewide candidates were selected for what would become the Republican Party.

United by desire to abolish slavery, it was in Jackson that the Platform of the Under the Oaks Convention read: "…we will cooperate and be known as REPUBLICANS…" Prior to July, smaller groups had gathered in intimate settings like the schoolhouse in Ripon, Wisconsin. However, the meeting in Jackson would be the first ever mass gathering of the Republican Party.

The name "Republican" was chosen, alluding to Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party and conveying a commitment to the inalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

But really… not so much — or at least, that's certainly not the origin moment of the party, nor the most direct influence for its name. This is not a particular dig at the GOP — because in fairness I must note that the Democratic Party website sums up its earliest origins by saying they've been around "more than 200 years", and leaves it at that. Incorrect or incomplete interpretations of history are a bipartisan issue, and an appallingly bad one at that. Getting it right and remembering how it all played out benefits everyone.

An important and little-known part of that history started like this: Travelling the same Connecticut River which would later power the industry of Holyoke, printer's apprentice Samuel Bowles was ready to strike out on his own. Coming north from Vermont, he'd gotten on a flatbed boat with his family and a small printing press in 1824, and started a weekly newspaper in Massachusetts called the Springfield Republican — often referred to as simply The Republican.

Samuel was the second of four generations of Bowles family men to have that name — three of whom would run The Republican — which according to a 1934 Time Magazine piece, led to a "the beery compositors" of that paper to make up a rhyme about how when one Samuel Bowles got old and died, there was another to take his place. In his July 13, 1824 prospectus explaining his reasons for launching the paper, Samuel Bowles II explains his political reasons for doing so directly in the wake of the failure of another paper in nearby Hampden, Massachusetts:

Circumstances induce the subscriber to believe that the establishment was owing to other causes than the want of a disposition among the republicans in this quarter of the State, to patronize a paper whose course shall be governed by genuine republican principles. It is his determination that the Springfield Republican shall strictly adhere to those principles; and when he considers that in the county of Hampden there is a decided majority of republicans, and that in the two counties of Hampshire and Franklin the party in point of numbers is respectable, and that in neither of these counties there is a paper devoted to the republican interest.

It catches my eye here that in this same debut issue that explains the Springfield Republican's reason for being, then-rising-star Massachusetts political figure Edward Everett is mentioned. Everett would go on to be U.S. Secretary of State, Governor of Massachusetts, president of Harvard, an orator of national note who shared the dais with Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, and also — an ancestor of foundational American golden age comic book creator Bill Everett.

We should also note that the term "Republican Party" has been in common usage in the United States since the 1780s. The party founded by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson which is now known as the "Democratic-Republican Party" was much more commonly known as simply the Republican Party at that time. A glance at the data via historical newspaper mentions of the party tells me that the term "Democratic-Republican Party" did not come into vogue until the 1870s.

While many feel that this was simply a way to differentiate Jefferson's party from the current Republican Party which formally began in 1854, the notion that the current Republican and Democratic parties both have their roots in Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party leads one to a far more important reason. And as Jefferson himself brilliantly put it in an 1824 private letter:

Men by their constitutions are naturally divided into two parties. 1. those who fear and distrust the people, and wish to draw all powers from them into the hands of the higher classes. 2. those who identify themselves with the people, have confidence in them cherish and consider them as the most honest & safe, altho' not the most wise depository of the public interests. In every country these two parties exist, and in every one where they are free to think, speak, and write, they will declare themselves. call them therefore liberals and serviles, Jacobins and Ultras, Whigs and Tories, Republicans and Federalists, Aristocrats and Democrats or by whatever name you please; they are the same parties still and pursue the same object.

The Showman and the Iron Man

In 1844, Samuel Bowles III took over the paper his father had founded. Young Bowles was just 18 years old at the time, and perhaps because of his youth he realized something that has made several large fortunes both before and since his time: the information landscape is always changing, and always accelerating. As Bowles later noted about "The New Journalism" that he helped create:

American journalism was undergoing the greatest transformation and experiencing the deepest inspiration of its whole history. The telegraph and the Mexican war came in together; and the years '45-'51 were the years of the most market growth known to America. It was something more than progress, it was revolution.

The journalism was yet to be created that should stand firmly in the possession of powers of its own; that should be concerned with the passing and not the past… and should command the coming times with a voice that had still no sound but its echo of the present.

Obviously no stranger to the power of a potent turn of phrase, it came to pass that Samuel Bowles III formed a close friendship with Whig Party mainstay and US Representative from Massachusetts Edward Dickinson and his family — and in particular, Dickinson's now more famous daughter Emily Dickinson, important American poet. Dickinson wrote some 40 of her poems in letters to Bowles.

By 1854, Edward Dickinson and the rest of the Whig Party was on their heels due to the rise of the nativist Know-Nothing Party and their propaganda tactics (Dime novelist, Buffalo Bill promoter, political agitator and showman Ned Buntline, as well as dime novelist and traveling performer "Iron Man" A.J.H. Duganne were both founding members of the party). About the Know Nothings, Bowles wrote in a March 31, 1854 editorial:

Secret political organizations, in a Republican government, are in the last degree reprehensible, though we doubt whether they ever become dangerous in America, for the principles and good sense of the people must be against them.

…Organized opposition to any portion of our population must beget opposition, and tend to keep alive the prejudices and influences which it is for the interest of all to do away with.

Bowles would soon realize that he had underestimated the Know Nothings. The secretive party's anti-immigrant and anti-abolition stances created deep divisions among the Whig Party in both North and South. The breaking point then approached: if it passed into law, the Kansas-Nebraska Act would repeal the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which prohibited slavery north of the 36°30′ parallel, excluding Missouri. Under the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the residents of each territory which would become a state could vote to decide the issue of slavery in that state. This law also came with a critical complicating factor: "resident" was defined as any white male over the age of 21 who declared that he was a resident of the state. In other words, anyone could move to Kansas, declare himself a resident, and help decide the fate of slavery in the state. Of course, we know from history that the predictable chaos would ensue as a result… and then some.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed on May 30, 1854. The next morning, the front page of The Republican was practically ablaze with reactions. As one letter-writer put it:

What is the reason all true anti-slavery men in this state cannot unite in the coming fall election upon a common platform and the same candidates? Let the organization be known neither by the names of the free-soil, whig, or democratic, but simply as the "people's party."

If we let the present opportunity go by, we shall be slaves forever. While the old parties at the North have been engaged in quarreling with shadows, the slave power has been strengthening its power and enlarging its domain. In the present emergency, why should we not act like men, instead of children?

In an editorial on the same front page, Samuel Bowles III took up the call:

The national Whig Party is surely a defunct institution. It has been tottering for some years, resorting to various expedients to maintain itself, but has finally gone by the board.

Denounce political death to all Northern congressmen, cabinet ministers or presidents who permit themselves to falter in opposition to slavery-extension, and announce the doctrine that freedom should be hereafter national…

…The Whigs of the North may revivify their local organizations and form the nucleus of that truly national party of freedom, which the times so sternly demand, and the people are so loudly clamoring for.

It seems that many among the party heard these calls loud and clear. That same morning, about 20 Whig Party members of the House met in the rooms of Edward Dickinson and Thomas Elliot, the representatives from Massachusetts. Most present were convinced that a new party was needed, and the name "Republican" was agreed upon — inspired in large part by the old party name kept alive by one of the leading political newspapers in the country, which was published in Massachusetts, by Edward Dickinson's friend. The Republican newspaper had become one of the guiding voices of the party at its foundation.

The Fabulous Drama of Sherman Bowles

In 1945, The Federal Register reported that the War Production Board issued a suspension order against Holyoke Publishing Company for a violation of wartime quota regulations. In brief, the War Production Board found that Holyoke's ownership of titles formerly owned by Victor Fox and Frank Z. Temerson, "Was temporary only, and for the sole purpose of enabling it to obtain sufficient profits form the publications to pay off debts previously incurred by the Temerson and Fox interests to Holyoke." As such, Holyoke was not entitled to use the paper quotas arising from the publication of those comic book titles on their other titles going forward. Holyoke had thus used 775,772 pounds of paper in 1944 for the comic book series Sparkling Stars in violation of War Production Board Limitation Order L-244. It would appear that the resourceful Sherman Bowles eventually found his way out of that situation. The Sparkling Stars series halted with Issue #9 cover-dated February 1945, and resumed about a year later with the Sparkling Stars #10, cover-dated February 1946.

The book Bowles History and Related Families notes of Sherman Bowles:

Although he was born in the newspaper business, Mr. Bowles early in life made a work-study of the publishing industry. While he seldom devoted himself to actual editorial pursuits, he wa a skillful writer who, upon his occasion, could set down his views in forceful succinct words.

Sherman Bowles' death is like the closing of some fabulous drama that encompasses a whole era. Many will try to read it, but no one will wholly understand it, for the stories will be conflicting. The hero, a financial wizard, a man of impulsive generosity, but still a lonely man…

Sherman Bowles died in March 1952 at the age of 61.