Posted in: Comics, Look! It Moves! by Adi Tantimedh | Tagged: animanga, anime, comic con, Comics, japan, manga, new york, NYCC

Wikia's The Masters of Animanga – Look It Moves NYCC Special by Adi Tantimedh

Adi Tantimedh writes;

One of the events at NYCC 2013 that was a big deal but went under-reported was the Masters of Animanga panel to commemorate the successful conclusion of their fan-driven collaboration with several manga and anime masters

The Wikia website started out as a variation on Wikipedia, a web hub for fans of anime, manga, video games, movies and pop culture to post news, lore and background information on favourite topics. Even I've used a wikia page to check a walkthrough for a video game or an episode guide for an anime series. What you may not know is that Wikia has grown into a central web hub for anime and manga fandom, a place for the fans to gather and share news, even post fanfiction.

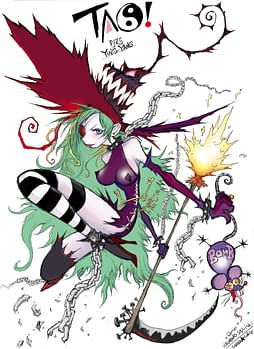

The Masters of Animanga writing project took Wikia to the next level: Wikia engaged a group of professional manga and anime masters from Japan to create characters and pitches in three different genres, posted character artwork and opening chapters in prose for fans to write the next chapters of the story one new paragraph at a time, a large, sprawling online Exquisite Corpse, if you will. It's worth watching the lavish introduction video on the wikia page to get a taste of its ethos.

The manga and anime masters were Lone Wolf & Cub creator Kazuo Koike, veteran anime producers Masao Maruyama and Hiroaki Ikegami, founders of anime studio Madhouse (and producers of the Ninja Scroll and Trigun anime), Afro Samurai creator Takashi Okazaki, and manga artist Sin'Ichi Hiromoto. The creators oversaw the project in an executive producer capacity, and the project was unique in the way it had industry pros interacting with fans in a way that doesn't usually happen in the US comics industry. That Wikia had flown them over – including industry giants like Koike and Maruyama – to NYCC made it a very big deal.

At the press roundtable after the panel, journalists were curious about the value of such a project. These manga and anime creators were busy men back in Japan after all. Why were they spending some of their time on a potentially chaotic project like this? Their consensus was that it gave them invaluable insight in how American fans thought and worked. It also created a safe space for aspiring creators to practice their craft and learn the basics of storytelling, of world-building, of character-creation and design, and so on. There was an impulse to help train what might be the next generation of creators. Back in Japan, Koike has taught manga writing at two universities and also runs his own intensive manga cram-school which sounds like a manga dojo, and his former students include many who have since gone on to create popular and successful manga and anime series since the 1980s.

To me, what the project proves is the deeper level of engagement the manga and anime industry has with its fans both in Japan and abroad, since the US comics industry does not really open itself to this degree of interaction outside of conventions. The doujin industry, where fans create their own fanfic versions of popular manga and anime, is encouraged and the next generations of professional creators habitually emerge from the scene. The Japanese creators seemed surprised when I pointed out that a doujin or fanfiction scene is not really encouraged by US comics companies, who would issue legal cease-and-desist letters to fanfic works that are offered for sale in order to protect their trademarks. The writing project was, in effect, a massive online doujin project initiated by professional creators.

All the manga masters here were interested in creating work that appealed to Western and international audiences. They pointed out that the majority of works in Japan were generally created mainly for Japanese audiences, but in order for the industry and the culture to evolve and survive, it was important to reach out to audiences abroad, and their own works over the decades often had Western audiences in mind on top of Japanese audiences, drawing on Western art and pop culture influences as in the likes of Afro Samurai or the science fiction gunslinger series Trigun. Koike had a unique metaphysical take on manga, citing the right-to-left reading experience in Japanese in contrast to the West's left-to-right reading dynamic tended to have different effects on the mind, and should thus influence what types of stories were created and how they should be written.

When asked if they would want to do it again, the creators said they would, and next time, they would take a more hands-on role in critiquing and guiding the fan-creators' contributions to the story. Even Koike mused that he might be tempted to contribute through a pseudonymous username.

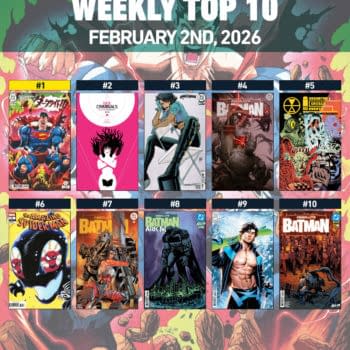

What I took from the project, the panel and the press roundtable is how big wikia and US manga/anime fandom has become, equaling if not surpassing superhero fandom. If you walked around the con, you would have seen that the huge number of manga/anime fans and superhero fans, as evidenced by cosplayers, were almost evenly split, yet both scenes seem separated by a huge cultural gulf. The main comics news sites on the web tend to all but ignore the manga and anime scene, as evidenced by the fact that I seemed to be the only one to report on the news of the Lone Wolf & Cub sequel while the other big sites were too preoccupied with news from Marvel, DC and the Hollywood studios. Manga and anime fans have various news sites they consult regularly to find out the latest news and wikia has grown into one of the biggest go-to sites, with its crowdsourced contributors creating a vibrant, far more active scene than even US superhero fandom has been. That the Masters of Animanga Writing Project has largely gone unnoticed by most comics sites is a telling indication of how cut-off they have become from the manga and anime side of the industry.

I am my own doujin parody at lookitmoves@gmail.com

Follow the official LOOK! IT MOVES! twitter feed at http://twitter.com/lookitmoves for thoughts and snark on media and pop culture, stuff for future columns and stuff I may never spend a whole column writing about.

Look! It Moves! © Adisakdi Tantimedh