Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Bart Simpson, Batman, Comics, dick tracy, entertainment, frank miller, gi joe, larry hama, spider-man, teenage mutant ninja turtles, Todd MacFarlane

Four Color Roots Part 2: A Strange Brew of Art Brut (1990)

By Christopher Smith

In this, the second installment of our ongoing column series, Christopher Smith takes us on a tour through his own back pages as a comics fan, going down unexpected dark alleys and digressions. Focusing only on the comics and pop-cultural touchstones he experienced at the time, he reconsiders their (at times unlikely) influence and impact from a modern-day context, and his own journey through the four-color and geek culture worlds that's apropos of so many comics fans and pros of the same generation.

Last time, he explored the brew of syndicated cartoons, aggressively marketed toys, and inherited pop culture of a more innocent time, which laid the groundwork for his later fandom.

A work of art is only of interest, in my opinion, when it is an immediate and direct projection of what is happening in the depth of a person's being… … It is my belief that only in this 'Art Brut' can we find the natural and normal processes of artistic creation in their pure and elementary state.

– Jean Dubuffet, 1967

Typhus, deteriorate them Epidemic, devastate them Take no prisoners, cremate them

– Megadeth, "Take No Prisoners," 1990

I was an awfully well-behaved child, perhaps frighteningly so. I have a distinct memory of my second-grade teacher telling me to lighten up, and perhaps smile a bit more. This might have been around the same time I do recall doing one thing that may have made my parents a bit annoyed with me: scratching a Bat-logo into the rear of the front passenger seat of their gray 1977 Toyota Corolla. It was a rainy day, and I used the wet sole of my sneaker to do so. I don't think I quite intended it to be permanent, but the scuffed mess stuck around until the Toyota went off to the scrap heap a decade or so later, as it was generally considered unsafe for me to inherit as a young driver.

The Bat-logo certainly lost something in translation, but it became something else in my juvenile mimicry. Strangely enough, that crude attempt at marking my parents' comfortable Carter-era two-door coupe was what now came back to me as I rode the bus to school in fourth grade. It was early in 1990, and Batmania was still in the air. Perhaps not as much as it had that previous summer, but it was a significant vector in popular culture. Our bus was an odd little DMZ for us, a place where, for the next three years, students attending my magnet school and a different, somewhat rougher-in-reputation one with which we also shared a playground and track, would mingle. There were vaguely sketchy boxed sour candy sales, pencil fights, and the stray cooler-than-the-rest-of-us kid who had brought in a boombox playing "Ice Ice Baby" or Megadeth's Rust in Peace. Our bus driver was an aging metalhead who welcomed the soundtrack. I now imagine he might also have approved of what my best friend at the time had brought with him, the leather-bound Complete Frank Miller Batman. Logic points to his having received it that Christmas, but I'm not sure.

If Secret Wars baffled me in 1984, seeing pages from 1986's The Dark Knight Returns, which I read over his shoulder, had an even more profound and unforgettable effect. I saw grids of TV-shaped screens in a row, and someone I thought I recognized as the crude caricature of a rosy-cheeked Reagan from the Spitting Image Genesis videos. Harvey Dent's scarred face (about which I'd learned in Mark Cotta Vaz's Tales of the Dark Knight, a 50th-Anniversary book that I'd checked out from a library the previous summer) went from normal to hideous to normal again within the span of a few panels. Above all was the scratchiness and brutality of Klaus Janson's inking, which only added to the cramped, grisly feel of the book. And did I see the Joker break his own neck? I understood, at this point, that a sinister Nicholsonian Joker was being depicted here, but there were other undertones I couldn't conceptualize. Nevertheless, it was all unsettling, clearly age-inappropriate, and something I didn't fully understand yet felt an innate need to explore. It was comics as Art Brut for the pre-adolescent psyche. It evoked a terror a bit like that of the Stephen King books I'd start devouring in a few years.

I checked Vaz's book out from the library again and read more, saw and studied some of the same panels reproduced in black-and-white. In addition to a crash course in past continuity's broad strokes, I was also starting to gain a faint sense of context and history for comics and their artists, and I would continue to encounter darker, altogether grittier, and more idiosyncratic personal visions of the hitherto squeaky-clean characters I'd first met a few years ago. Hindsight reveals this as groundwork being laid for the upheavals comics would soon undergo; to a child taking this all in for the first time, it was truly like an initiation into some secret society.

My taste in comics and other media during this time period was nowhere near as dark and scary as what Frank Miller was bringing in (nor is not now; I actually cringe a little at some of TDKR's excesses, as well as its creator's, today, and don't consider it among my favorite Batman comics). And yet everything seemed to bear his influence. Turtlemania was a case in point, an unbelievably toyetic property that took everyone by storm circa 1989-1990, yet rose in its origins from a black-and-white, initially self-published title that parodied the grit of Miller and his Daredevil run, among other trends burning up the comics scene circa 1984.

I'm not entirely sure how I first discovered the Turtles, but I was soon soaking in the weekday afternoon airings of the cartoon, and eagerly sinking my quarters into the four-player arcade game first released in 1989. I traded rumors about advanced levels and hidden Easter eggs within the game and its NES home counterpart among friends on our playground; not being the most athletic, we favored long strolls around the track while others engaged in touch football and pretending to date each other. The action figures, too, were something my friends and I all considered ourselves too old to, exactly, play with (perish the thought), but they were something to collect and display. I certainly had my share, though my collection paled in comparison to other, perhaps more affluent kids my age, the Starter Jacket crowd, often seen displaying the iconic Basketball-team-emblazoned coats in the arcade settings. Intimidation and menace were nascent tools of preteen masculinity.

When I convinced my mom to buy me the First Comics collected reprint of those early Eastman and Laird issues in our local mall Waldenbooks, I again was a little taken aback at their contents. These turtles didn't have brightly colored bandanas, quip about pizza, or battle comical bad guys. Instead, there was a hand-drawn kinetic energy to the artwork that the animation lacked, as well as a Byzantine level of detail. The comic almost looked like the work of us kids—a Ninja Turtle face was one of the easiest quick doodles you could do while daydreaming through Math –only with a level of intricacy and talent we could only dream of. Sure enough, as in TDKR, Shredder appeared to have been killed—pulverized—at the end of this comic. There was also a bit of profanity, and the shocking sight of April O'Neil in a jumpsuit that was quite unzipped. I now traded rumors with friends who had the other trade paperbacks. What could Eastman and Laird possibly do for an encore?

1990's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film was a bit of a revelation, too, owing more to this comic series than the cartoons. That was a great selling point, at the time, and served as a gateway into maturity for those of us who were picking up signals from pop culture geared towards those deeper in the throes of adolescence than us. Revisiting the movie recently, I found that (in contrast to its sequels) it's held up quite a bit better than one might expect. Its vision of a dystopian New York City in which its urchin-like neglected kids thrill to the fantasy of joining a literal underground ninja street gang—its lair complete with all the signifiers of rebellious youth culture at the time, such as a skateboarding half-pipe and arcade cabinets—was certainly appealing at the time, and spoke to a generational discord.

Some were these lost kids, who Sam McPheeters, writing about the early 90's punk scene, called "a sea of disinterested young boys with backpacks"; others feared them. The shockingly obedient child that I still was in 1989 had become someone who struggled academically, a kid who was rather introverted and lacking in self-esteem, and who suddenly had to cope with bullying from children and adults alike. The world got uglier and more complex, brimming with paranoia about drugs, kidnappers, Satanists. Things got scary and lonely in these East Coast suburbs. For my friends and I, in our relative isolation, comics became a necessary outlet, an escape, even if they mirrored the world in their darker aspects.

Another comic that revealed a kind of parallel universe revealed through a pop-cultural wormhole, was Matt Groening's Life in Hell, which another best friend had in a collected paperback edition purchased from that same mall bookstore. The then-still-controversial The Simpsons had also premiered in December of 1989, and led—among its other respectable merchandise—to a flood of bootleg T-shirts that not only dealt with political touchstones of the era such as the Gulf War in startlingly xenophobic and offensive ways, but embraced the smart-alecky qualities of Bart himself, and even obliquely commented on the Simpsons/Cosby Show racial divide that I recall happening in those next few years, by recasting Bart as African-American or even Rastafarian. Life in Hell almost seemed to have been produced by the same mischief-making trickster god, only a smarter one: a black-and-white comic done in what at times approached the Simpsons house style, but commented on the everyday miseries of school, work, and romance through world-weary rabbits with those same telltale bug eyes and rounded teeth. The title itself shocked me, and broadcasted that it was not something I'd be allowed to buy, check out from the library, or bring home (At the time, I even remember thinking Heluva Good cheese was startlingly frank in its nomenclature. I was a pretty delicate boy).

Mad magazine offered parodies of New Kids on the Block, but this was something different, funny and true. It still largely went over my head, but I connected—and still connect—with it on an important level. I'd just been introduced to independent comics and their offbeat sensibility, and had yet to realize it. I imagine the effect was somewhat like a kid today who had grown up the Marvel house style suddenly encountering Matt Fraction's Hawkeye, Michael Fiffe's Copra, or even Julia Wertz's Drinking at the Movies. Are those kids out there? I certainly hope so.

If I knew pop-cultural exhilaration at this time, I also knew disappointment. 1990 brought the Disney-funded Dick Tracy film, arriving on a boatload of hype and audience goodwill left over from Tim Burton's Batman. I had no idea who Warren Beatty was or why he might have been an interesting choice as director/star; I just loved the bright colors and bizarrely made-up villains. I followed production notes in magazines, and even owned an official making-of tie-in book. I somehow learned that a midnight sneak preview screening came to my town, but was aghast at not being allowed to go. The following week, I saw a man in a T-shirt obtained at that screening at the same mall bookstore where I'd gotten the Turtles comics, and seethed with jealousy.

But I finally roped my mom into dragging me to an early showing opening day, and was not exactly captivated. It was, and is, hard to explain why it seemed like an inert experience. I have no idea what my young expectations were, but this film didn't quite meet them, not as Burton's had. Perhaps it's best remembered as a misstep in the history of the genre.

On the more corporate side of things, Marvel was not without its charms. More popular than the comics among my cohort were the Marvel Universe trading cards, which may have been what got me to go to my first comic shop, sometime late in 1990 or early 1991. In pursuit of the ever-popular and mind-boggling hologram cards, we amassed piles and piles of them, which the true devotee would keep in a three-ring binder. While DC published big retrospective books on the history of its characters, Marvel had yet to do so (but would, by 1993's Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics). Instead, and in a bold move of their trend-chasing, they published an elaborate set of cards, which boasted not only the aforementioned elusive holograms, but detailed statistics on each character's intelligence, agility, strength, and other attributes.

There was even a subset of "M.V.C." (Most Valuable Comics) cards reproducing the covers of landmark issues, and "Famous Battles" cards, commemorating important clashes between superheroes and teams, leading up to Chris Claremont's late tenure on the X-Men, and the already popular Todd McFarlane-drawn issues of Peter David's The Incredible Hulk. The cards themselves featured striking artwork from the likes of John Romita, Jr. and Art Adams, whose names I would be learning in the years to come. The less said about the corny Stan-Lee-written (?) joke cards, the better. But for a budding young fan years away from the internet, they were quite a resource, a tool that taught the user how to interpret and view the concept of a shared publishing universe. I wanted to read those key M.V.C. issues, but would soon prove frustrated when setting foot in comic shops within the next year, seeing them all mounted in plastic on the wall with two-and-three-digit price tags. It was the equivalent of walking into a bookstore and finding plentiful copies of Fifty Shades of Grey for a dollar, but Moby-Dick and Pride and Prejudice locked in a glass case, to be kept in mint condition. The gatekeepers would still win out, and for a while yet, as the speculator boom was just getting started.

Spider-Man was a character I would meet the slightly outmoded, squeaky-clean and aesthetically radical, cutting-edge versions of within a few months of each other. October 1990's Marvel Tales 242, a comic I bought offhand while looking for Panini sticker packs for my Ninja Turtles sticker album, featured Spider-Man teaming up with Nightcrawler under the big top, and actually reprinted January, 1980's Marvel Team-Up 89, by Chris Claremont and Rich Buckler. I recognized Nightcrawler from trading cards, and he was already announced by one of my two best friends as his favorite character (he had a cool older brother who was into the X-Men, Pink Floyd, and Douglas Adams). I was intrigued by his demonic appearance (amazingly, my mom didn't forbid me to buy it for that very reason), and took the comic home, reading and rereading it obsessively, even the Rocket Racer back-up.

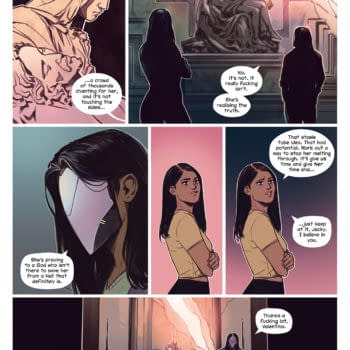

Published simultaneously but discovered by me a few months later, Todd McFarlane's Spider-Man couldn't have been more different. Much has been written about how McFarlane brought a Steve Ditko sensibility back to the character, contorting him into bizarre poses, draped ornamentally in tangled knots of webbing. I've also read many critical digs at his writing skill, especially in the five-part "Torment" arc that opened his run on Spider-Man, a title which he was given, essentially as a showcase for his artistic skills. At this age, though, I found it compelling reading (and it certainly didn't go over my head like Frank Miller). In this story, Spider-Man was torn and bloodied, subjected to occult rituals and a ravenous, terrifying Lizard. "Pray for our hero," the end to one issue read, ominously.

Along with the similar abjections offered by Jim Starlin and Bernie Wrightson's Batman: The Cult, which I think I rescued from fifty-cent bins at conventions the following year, I saw everything I was starting to want in a superhero comic at this age. Blood, guts, psychological turmoil, exaggerated and hyper-detailed anatomies, terrifying villains. Decades later, I saw a lot of this reflected in Scott Snyder's first Batman arc, which seems like the platonic ideal of the kind of story I wanted (and would later read, in Knightfall) as a preteen. Sure, I liked Marvel Tales—which boosted its sales a bit with McFarlane-drawn covers—just fine, but the old order was obsolete. The new age had begun.

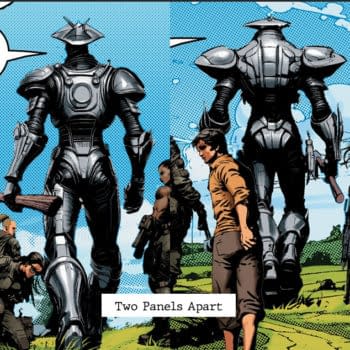

Meanwhile, the Gulf War had begun in August of 1990. Everything was televised on CNN, and there were even "Operation Desert Shield" trading cards; it was all perfect for the young consumer. It fit right into this developing zeitgeist. Next time, we'll examine how Larry Hama's G.I. Joe challenged this status quo, and other new developments in comics and animation circa 1991.

Christopher Smith teaches composition at Columbus State Community College and has spent about two thirds of his life being obsessed with comics, music, and the strange, somewhat overlooked corners of pop culture. He lives with his wife, son, and two devious cats.