Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: action lab, adam kubert, Avengers #32, Comics, dc comics, dynamite, entertainment, Grayson #1, image comics, Justin Jordan, larry hama, oni press, Southern Dog, spread, The Life After, Thor's Comic Review Column, Turok: Dinosaur Hunter, wolverine

Thor's Comic Review Column – The Life After, Turok, Avengers, Moon Knight, Lazarus, Captain Marvel, Wolverine, Grayson, Southern Dog, Spread

Thor's Comic Column: Back in 2002, an aspiring comic writer named Sean Fahey launched a comic-review column with a vaguely "Viking" name, and a mission to cover something more interesting than plot rundowns of the latest Big 2 crossovers. He recruited a crew of like-minded writers, comic book enthusiasts from several walks of life, and the column grew to feature reviews and think pieces that span the history of the sequential art medium. Sean has since moved on to write and edit the Tall Tales From the Badlands horror/Western comic series, and this week, the Thor crew makes their debut at our latest port of call.

This Week's Comic Reviews Include:

The Life After #1

Turok: Dinosaur Hunter #6

Avengers #32

A few words on Moon Knight, Lazarus, Captain Marvel, and a look back at Larry Hama and Adam Kubert's Wolverine

Grayson #1

Southern Dog #1

Spread #1

1. The Life After #1 (Oni Press, $3.99)

By Graig Kent

The Life After is writer Joshua Hale Fialkov second foray with the Oni family (after The Bunker). When put alongside established but underappreciated names like Cullen Bunn, Charles Soule, Anthony Johnson, and Ted Naifeh, one can certainly see how he fits. After reading the first issue of this new book, one also sees how it compliments a line-up of ongoing titles that includes The Sixth Gun, Wasteland and Letter 44.

The book does start off with a premise that feels all too familiar, following a man, Jude, living in an environment that's controlled, and seems to repeat itself on a daily basis. There's hints of The Matrix or the Truman Show, that Jude's existence isn't at all under his influence and that Jude's dour daily drudge is on a Groundhog Day-like repetitive cycle. As his existence retreads, handled exceptionally well in artist Gabo's densely panelled opening pages (the page 2-3 spread is an effective 10×5 grid of monotonous imagery), we catch the occasional glimpse of the controllers of Jude's world.

When Jude breaks his lonely cycle to pursue the woman who drops her handkerchief beside him every day by stepping off the bus, the world fractures momentarily around him, revealing a new world that is out of step with his own time. In this new world touching any of the strangers he encounters leads him into a dizzying mind meld of despair and ultimately death. All these people have histories of suicide, and Jude sees every desperate moment that led them to their fate. Jude doesn't catch on right away, not until it's spelled out for him…he's in purgatory.

But this isn't any conventional literary purgatory, this is indeed a controlled world, one where everyone is forced to live the life that pushed them into death over and over. What it means that Jude has gained that awareness and that he's found a likewise individual in Ernest Hemingway is naturally going to be the crux of the series.

Fialkov does employ heavily familiar concepts, but with a knowingness to it that allows him to manipulate their familiarity to his own ends. The whole "control room" angle, especially once Jude's awareness starts to influence his world, takes on comparisons to Whedon and Goddard's Cabin in the Woods, but again, employed to his own purpose.

Gabo's lines and figures aren't the prettiest on the stands but there's a confidence and consistency to his linework that elevates it. While his figures can be rigid, he's got an exceptional eye for detail which makes all the difference when Purgatory starts to fracture around the main character. It sets the anything-can-happen environment up perfectly. Beyond the figures on the page, the pages themselves are incredibly well structured. The aforementioned 50-panel spread immediately highlights Gabo's storytelling chops, which are continually put up to the challenge by Fialkov's demanding script (transitioning between environments in-story and jumping between environments in the meta-story, as well as handling a few flashbacks which must be both terse and effecting) and is more than well-met. This opening chapter, though only 22 pages, feels like at least double that thanks to the sheer amount of visual information Gabo is able to dispense, and dispense well.

Gabo employs both artistic and computer-assisted effects to enhance the unusual and surreal world this purgatory is, creating a very specific series of visual representations for when Jude touches someone and receives their suicide story, and the transitional effect on the panel itself when it goes in and out of flashbacks. Beyond this, Gabo's coloring is brilliant in establishing the dull grey life that Jude repeats over and over, highlighting the bright spots, like the dropped red hankerchief. As Jude moves further and further away from his familiar world, the colours lighten, getting grim again in flashback, but at their most vibrant when Hemingway makes his way onto the scene, full of awareness. It's in large part this coloring choice that moves the book from potentially being too dark and heavy to having a hopeful and even sunnier and rollicking disposition that the gaggle of oddball characters on Nick Pitarra's blue sky cover seems to promise. I also particularly like the green-light tinged monitor room of purgatory's controllers…the significance of the green light and Gabo's 80's-styled monitors give off a less-than-modern vibe to the operation.

It's a successful and surprising opening chapter that seems to be leading to a series as fit for monthly consumption as the trade paperback collection. I'm certainly keen to see where things go from here, and definitely curious to find out how this world came to be. Interest piqued!

Graig Kent keeps promising to finish the final edit on that novel, play test that board game, start drawing that web comic, find an artist for that children's book, and maybe write that teleplay, but first he's got to read that pile of comics and watch that backlog of movies…and those kids won't put themselves to bed. He's been reviewing things for over 15 years. He's rarely on twitter @thee_geekent, he sometimes writes about movies, and his dog has a blog.

2. Turok: Dinosaur Hunter #6 ($3.99, Dynamite)

By D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

The Khan's armies thundered through great swaths of Asia and Eastern Europe, pressing several of his Mongol's advantages in skill, cunning, and sheer brute warfare. The Khan did this with such speed and ferocity that he could realistically claim that, under the mandate of Heaven, the world was already his. Resistance to the Mongol Horde was not self defense. It was treason, and that would be dealt with most harshly. Genghis Khan's goals, other than loot or booty, are largely unknown, but generations after him would claim that the great Khan had brought order to the countries he had conquered. While his descendants may have had a point about uniting the Steppe tribes, I doubt that those who saw the destruction of the Islamic Golden Age or the Khitans would feel quite the same way. And even in the newly ordered Steppes, untold gallons of blood were brutally and sadistically spilled to reach that point.

If the Victorians had remembered this, I don't know what it would have changed. Likely not much in the material sense. But maybe they would not have lied to themselves about what their colonial ambitions were about, and maybe the would have seen themselves in the mirror of their subject peoples' histories. For that's what history tends to become, especially the histories of different culture. For all of the differences, certain patterns emerge, but in the end the same virtues emerge. And the same darkness.

I've wanted to love Greg Pak's run on Turok. While it has been good, Pak has felt like he's struggled to find a real voice for the series. I think this might be because Pak has two main drives that he's trying to satisfy with this unexpectedly ambitious series. One is to give fans of Turok the action-adventure character that they've been missing for years. The other is to explore his own alternate history. These elements never really gelled in the series' first arc, as Pak set about laying out bread crumbs for Turok to follow (where were his parents from, anyway?) and telling a ripping yarn about a small tribe of Native Americans meeting Templars. Templars with Dinosaurs. While Templar Dinos, brought to splendid life by artist Mirko Colak, are indeed awesome, Turok struggled to come to life in terms of its themes. In terms of overall quality, it felt as if the title was fighting admirably with one hand tied behind its back.

The new arc has fared much better, with the fifth issue taking some time to properly find the character of Turok as he has a brief, unconsummated affair with the Pterodactyl-riding Altani, captain of Genghis Khan's Skyriders. It's brought to an end by the interruption of a troupe of mammoth riders from the city of Cahokia. In this issue, it is revealed that the people of this western city are, in fact, Turok's people. That is, if he can be said to have a people. A common refrain in the series has been the character's muttering to himself, "Alone is better." What's more, his parents were exiled from this place, and were outcasts from the tribe that took him in. With these revelations, Pak's take on the character solidifies a bit, putting him in a similar mold to a character like Conan, an outsider who has to deal with the various injustices and iniquities that seem to be at the heart of civilization.

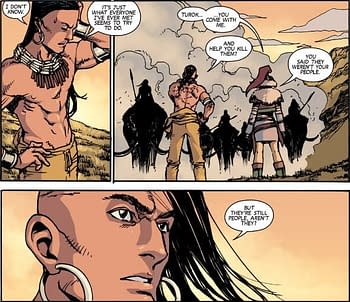

In placing the series in an alternate history, Pak also let's the series become about history itself. The first arc featured Europe descending on the East, and here the Mongols are descending on the West. Where the first arc got the "white devil" out of the way, the inclusion of a different imperial culture really lets the big picture themes of Pak's Turok breathe. Where Conan dealt with the "softness" of civilization, Turok deals with its brutality. This is particularly clear in an exchange between Atani and Turok in the sixth issue (Note the gorgeous Tak Miyazawa artwork):

Altani echoes the history written by Genghis Khan's actual descendants. Conan sought to fulfill his appetites. Turok seeks to survive, and then solitude. But Pak writes the character with a beating heart that can't help but be drawn to other people through the sheer force of his own empathy. Where Conan was hardened by his isolation, Turok is softened by it. Or maybe that's not the right word. If Conan's hardness was a strength that allowed him to conquer civilization, maybe Turok's softness is a strength that will let him push against civilization's brutality?

What is emerging in this series about a Native American who fights dinosaurs is a story that's not about that at all. Rather, it's about a man who has grown up outside of history confronting the human darkness at its center. Is Turok a skilled survivor and warrior? Unquestionably, and fans of the steely-eyed take that Tim Truman and Rags Morales gave the world in the nineties would do well to catch up on this series. But more than that, Turok is a character that speaks with the weary voice of the dispossessed, and his hurt has made him skeptical of civilization's fruits, and better able to see its brutalities, perpetrated by pretty much every group seen in this series, for what they really are.

And it must be said, Miyazawa's art is incredible here, and perfect for this arc. His manga-esque style brings just the right energy to story that prominently features a Mongol warrior woman who flies around on a Pterodactyl. He also finds Turok's innocence, allowing his bemusement at the darkness of history to be felt from a place of honesty rather than cynicism. There's also a sequence at the end featuring dueling panoramas that's a real treat.

Turok: Dinosaur Hunter is a series well worth catching up on, especially as it gains surer footing of its characters and themes. If you've checked out on this series, this second arc is well worth a chance. Highly recommended.

3. Avengers #32 (Marvel, $3.99)

By Cat Taylor

While the plot of the story is focused on Captain America trying to use these visits as an opportunity to learn what he has to do to keep Iron Man and the Marvel Illuminati from destroying alternate Earths in order to protect their own, the main interest to me is seeing the worlds that Hickman creates. Each future world is pretty interesting, but I'm a bit of a sucker for alternate Earth and time-travel stories anyway. The only thing that kind of bothered me is that the versions of the Avengers in this story 5,000+ years in the future all appear to be based on the modern Avengers. It's difficult for me to accept that several new and completely original Avengers wouldn't have become prominent members of the team during a 5,000 year time span, but I guess that's a pretty minor complaint.

Despite my interest in these future worlds themselves, they are technically background and plot devices for Hickman to explore philosophical issues through discussions between Captain America and other characters. It will be interesting to see the ultimate outcome of these travels, what happens to Captain America's outlook, and how he relates to the Illuminati as a result of his experiences.

However, I'm not certain that Hickman is playing fairly with established Marvel rules on time-travel. Hopefully, I'm not giving too much away to anyone who hasn't read this issue but one of the key moments in this issue is Captain America basically being told that everything is pre-destined and that therefore he's agonizing unnecessarily over certain actions and decisions. Conversely, if I recall my Marvel Universe history correctly, decisions and actions taken by characters can create any number of parallel universes that result over choices made or not made. In fact, aren't the various alternate Earths that are the focus of this dilemma the results of divergences in significant choices that were made? Whether there is going to be an explanation for this seemingly inconsistent predestined future or not remains to be seen. Regardless, I'm confident that the story getting there will be entertaining.

Much like Hickman is a trusted Marvel writer and has therefore been given two of Marvel's most important books, the art is being handled by two of Marvel's well-established artists, Leinil Francis Yu on the pencils and Gerry Alanguilan taking care of the ink. Like most established Marvel artists, they are good at what they do. Panel layouts, backgrounds, characters, etc. all successfully illustrate the intent of the story. There is also an interesting blending of the common muscle-bound superhero figure with a more modern sketchy, angular look that many of the independent comics are using lately. However, what really shines, art-wise, is the color. Colorists tend to be ignored in comic book art critiques and that's often because a single issue doesn't give them a lot of environments with which to work. This issue, on the other hand, puts characters in a variety of situations where the colorist, Sunny Gho, gets to explore various shades and how they are affected by the light. It's a case where using the colors to maximize the scene truly adds to the atmosphere.

As fun as this issue has been, I'm really looking forward to the next issue to see what Hickman does with a Marvel universe over 51,000 years in the future. Although, no matter how good it is, I'm going to be pretty hard-pressed to accept versions of Hawkeye and Black Widow still being around THAT far into the future.

Cat Taylor has been reading comics since the 1970s. Some of his favorite writers are Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, and Kurt Busiek. Prior to writing about comics, Taylor performed in punk rock bands and on the outlaw professional wrestling circuit. During this time he also wrote for music and pro wrestling fanzines. In addition to contributing to Thor's Comic Column, Taylor also writes fast food fish sandwich reviews for Brophisticate.com. He has the dubious distinction of not having a Twitter account.

4. Loki Charms and Tribbles 'n Bits – A Recommendation Rundown

By Adam X. Smith

*coughs, clears throat*

In a world, where reviews need to arrive on time or risk vanishing into the long grass that is the interwebs…

When there's only so many column inches you can devote to your favourite writer before it starts to become weird and stalkerish…

And when you absolutely cannot bring yourself to write more than 50 words about the latest company-wide crossover involving everyone else's favourite superhero…

There is… the mini-review.

Issue 1 went to three printings, and 2 and 3 went to two printings, and so I consider that a job reasonably well done […]The job has been, simply, reactivating Moon Knight as a productive property for the Marvel IP library. And, in personal terms, producing six single stories that held together, because I thought it would be amusing to provide a book that could be entered at any point and still give the reader a complete experience. Which goes against the grain a bit, because the modern commercial-comics reader has been very much entrained to expect long arcs rather than singles. I'm sure there are plenty of complaints out there about the lack of character arcs or long stories. But the book is still getting bought and reordered. So I guess we found an audience after all.

That was what Warren Ellis said about his run on Moon Knight running to six issues. And now I have something to say: issue #5, entitled "Scarlet", is on the shelves now. Go buy it. I don't even care that my journalistic credibility lies in tatters as I exhort you, the huddled masses, to read yet another Ellis book – truly, I don't. It's good. Seriously.

Also in the Shut-Up-About-How-Good-It-Is category this week…

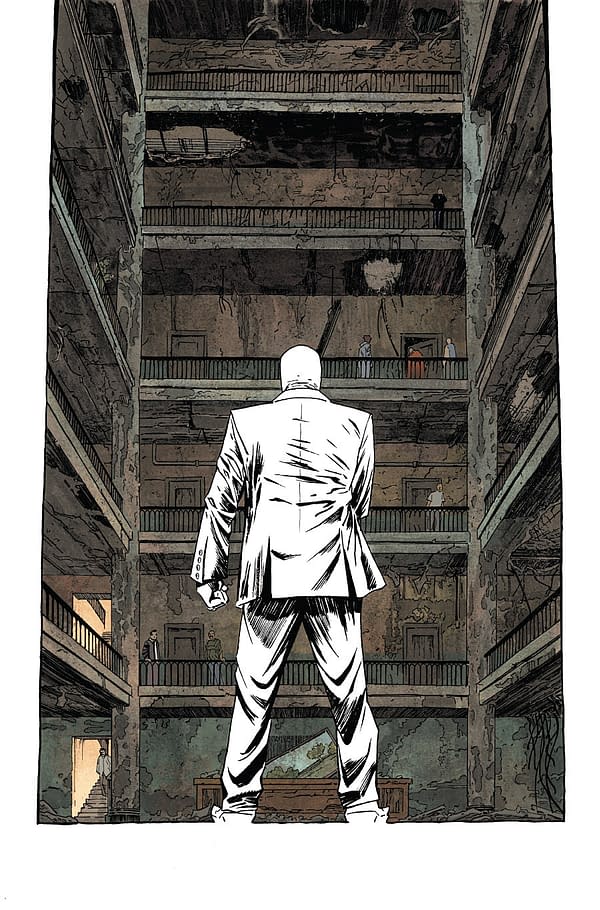

For those not caught up on Greg Rucka and Michael Lark's second arc of Lazarus, "Lift", it comes to a nailbiting conclusion with issue #9, in which the slowly unfolding origin of Forever Carlyle is given a sudden burst of context, and the Chekov's bomb is ultimately revealed. Moral of the story: never underestimate angry injured girls – especially if they're armed.

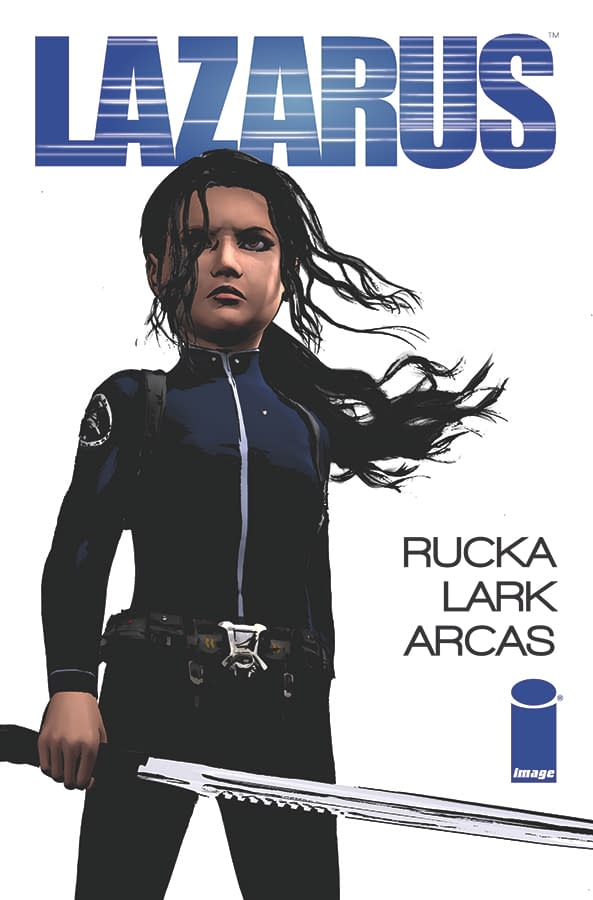

In other strong female character news, Kelly Sue DeConnick's cosmic retool of Captain Marvel, now in its fifth issue, is filling the sweet-spot in my heart for sassy and empowered blonde women currently left vacant by my inability to keep a lock on Buffy Season Ten's scheduling. The fourth and fifth parts of "Higher, Further, Faster, More" (which unsurprisingly is becoming something of a fan-community motto) doesn't quite wrap up the arc per se, but the conclusion – Carol Danvers, in space, without backup, and about to take on the Spartax fleet single-handedly to protect a planet of innocent galactic refugees – is exactly what I've come to expect from DeConnick's take on the character: brave, clever, driven, and resourceful; a heroine who is never afraid to stick her nose in where people tell her it doesn't belong, or to take responsibility for protecting people who are quick to dismiss her. If I might be so bold, I'd suggest that as a secondary motto the Carol Corps might consider "Always Outnumbered, Never Outgunned".

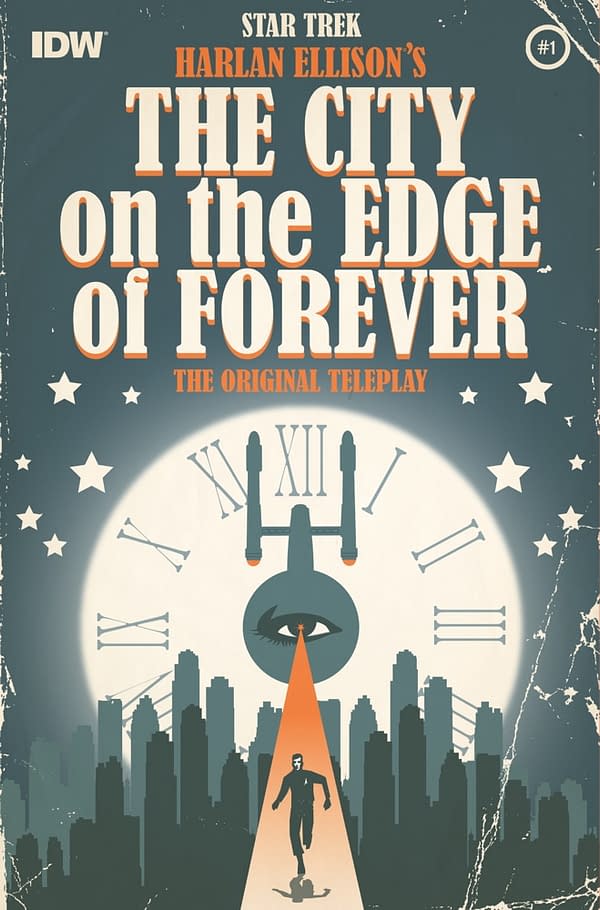

And finally, a recommendation for any classic Star Trek fans…

Some of you may have seen the Star Trek Original Series episode "The City on The Edge of Forever" written by Harlan Ellison. Well, for those who haven't seen it, or those who aren't aware, the episode went through several drafts and rewrites before it made it to the screen. So if you'd like to have a look at what could have been (sci-fi drug dealing aboard the Enterprise, cold-blooded murder, a more visually interesting planet than what could be achieved on a TV budget*), then I highly recommend reading the IDW adaptation by Scott and David Tipton with art by J.K. Woodward, presented as Ellison originally intended it – for whatever that's worth.

So yeah. That's what I've got for you this week. Some in depth stuff, some vaguer meanderings. That's pretty much how it is with me. Hopefully next week I'll be back with some brainings about Buffy Season Ten and Serenity: Leaves on The Wind. Peace out, y'all!

*The titular "city" in the show is portrayed as a generic desert with vaguely Roman ruined temple arches in it (one which was presumably reused pretty frequently), while the comic depicts it a little closer to Richard Donner's interpretation of Krypton, complete with glowy translucent crystalline structures and ice-cliffs.

Adam X. Smith is a paranoid android from the Planet X. For the last 27 years he has been living amongst the people of Birmingham, England (and more recently the University of Lincoln) ostensibly as a student of the school of hard knocks (also BA Hons Drama), but secretly on a mission to scout out the planet for invasion by alien forces; his weekly communiques on his various blogs are actually highly coded messages to his extra-terrestrial masters. He enjoys the musical stylings of local chiptune-metal band Elmo Sexwhistle, the fiction of Kim Newman, Kurt Vonnegut and Chuck Palahniuk, and his hobbies and interests include film-making, drama, occasional Youtubing, journalism and plotting the subjugation of humanity. He can be found on Youtube, Tumblr, Twitter or by jamming an ice-pick through the optic chiasm.

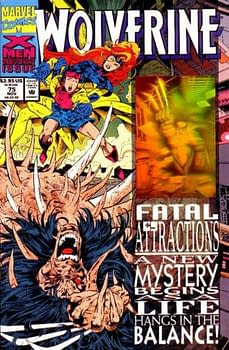

5. 'No Country for Old Man Logan: Masculinity, Mortality and Body Horror in Larry Hama and Adam Kubert's Wolverine'

By Bart Bishop

Hama was on the title for seven years from issue #31 in September, 1990 to #118 in November, 1997. During that time he took what quintessential X-Men writer b had already done with the character and refined it, uprooting Wolverine from his covert setting of Madripoor back to the United States for a years-long journey exploring his amnesic past, including fleshing out relationships, adversarial and fatherly, with the likes of Sabretooth and Jubilee. By 1993, however, the comic had been reduced to yet another X-title, with Wolverine donning his blue-and-yellow costume nearly every issue to take part in adventures that would be more suitable for the then-popular Saturday morning cartoon. The original mission statement of a solo Wolverine title, set forth by the classic Claremont/Frank Miller mini-series, was to show what Wolverine does when he's away from the X-Men. A course correction was needed, and Hama found that in the traumatic loss of Wolverine's epochal trait.

It kicks off with Wolverine #75, which functions as more of an epilogue to the multi-part "Fatal Attractions" storyline. The entire cast of X-Men abound, including 1990's mainstays like Gambit and Bishop, with the merry mutants attempting to return home from their battle with Magneto in space. After a troubled recovery, Wolverine attempts to prove his mettle in the Danger Room but in the process shows how far he's fallen with his bone claws erupting in a wretched "SCHUKK" that leaves him sanguinary and screaming. After a somber denouement in which Wolverine says goodbye to the team but more specifically to his sidekick and surrogate daughter Jubilee, he takes off on his Harley for parts unknown. The next half a year's worth of storyline focus on the ol' canucklehead testing his worth and paying his dues, leading to a few surprisingly poignant moments and horrifying visions.

Wolverine is a character defined by stereotypical machismo. He's violent, drinks hard, smokes cigars, rides motorcycles and even wears a cowboy hat, tying him to the Old West as a figure out of time. These visuals signifiers are the first aspects of the character to be removed, as he quits smoking after nearly hacking up a lung and leaves his cowboy hat behind with Jubilee in #75, gives up drinking after vomiting up "tasty whiskey" in #79, and even discards the Harley after #78, instead being chauffeured around for several issues, first by mysterious Landau, Luckman & Lake operative Zoe Culloden and then Native American tracker/pilot Harry Tabeshaw.

After #75 the blue-and-yellow costume isn't seen again until #79, with only the top revealed underneath his civilian clothing after Cyber tears into him, and not in full until #81. Both times this is contrasted against the bloodied bandages on his hands, a constant reminder of his being wounded that draws comparisons to over-the-hill boxers rather than the noble, righteous cattleman of myth, and after #79 the broken and twisted claws on his right hand. His paradigmatic unkempt, animalistic hair is exaggerated to an extreme degree under Kubert's pen, with the coloring leaning more away from the usual black and into gray territory, and his face is craggier and worn, possibly from age or the "tissue regression" mentioned by Moira MacTaggert in #81.

This withering of his male virility is also tied directly into his newfound mortality. Both are dramatized in the villains that he faces during this brief run: Lady Deathstrike, Cylla, Bloodscream and Cyber. There's always been a phallic nature embedded in Wolverine as personified by his claws, so by stripping them of their vitality and effectively neutering him. Hama renders the character impotent and wearied, while his enemies are unnaturally heightened. The women cyborgs, Deathstrike and Cylla, have forsaken their femininity but increased their power while the men, the vampire Bloodscream and adamantium-coated Cyber, are übermensches, reflecting aspects of Wolverine's own previous artifice and living-weapon makeup.

Wolverine and Deathstrike even share a romantic past, but in the face of his newfound limitations she gives up her bloodlust after a tender moment of mutual understanding at what they've both lost. Wolverine's encounter with Cylla and Bloodscream in #78 is about proving he's in his element out in nature completely in opposition to their perverse states, while the three-issue encounter with Cyber is about showing how Cyber is more-Wolverine-than-Wolverine, with bigger muscles and crueler claws. Twice Wolverine is saved by women, Zoe and Kitty Pryde, who ultimately defeat and capture Cyber, an inversion of the previous mentor role he's played for young women.

The intersection of these themes is in the vivid depictions of "body horror" through this succession of issues. Body horror is a sub-genre of storytelling that's main feature is the graphic depiction of destruction or degeneration of the human body. Filmmaker David Cronenberg is famous for popularizing this concept with his Videodrome (1983) and The Fly (1984) remake, his oeuvre revealing a fascination with the malleability of sexual iconography and thematic explorations of technology's effect on modern man, internal stresses externalized either mentally or physically. Kubert adopts the latter, taking Barry Windsor-Smith's lead from the seminal 1991 story arc "Weapon X", which depicts Wolverine perceiving himself in fever dreams as sprouting spikes from head to toe that bleed into wiring and monitoring gear, blending with psychedelic, Technicolor planes of desolation and madness. This is further explored by Kubert in waking scenes with the aforementioned distortion of the previously efficient and deadly metal claws into bloated, twisted shadows of their former selves.

The following months would see Wolverine shed the bandages, and with his claws healed he would don his costume more and more, eventually leading to narrative dead ends. For those seven months in 1994, however, Wolverine was a title that managed to deconstruct its star, with Hama and Kubert subverting expectations of what makes the character so enduring. Minus the costume, claws and capability, he was revealed as a complex character with deep melancholies and real pathos. Robbed of his manhood and invincibility, a man that had so long been defined by the physical learned to deal with his mental landscape, value friendships, and most importantly ask for help.

Editor and teacher by day, comic book enthusiast by night, Bart Bishop has a background in journalism and is not afraid to use it. His first loves were movies and comic books, and although he grew up a Marvel Zombie he's been known to read another company or two. Married and with a kid on the way, he sure hopes this whole writing thing makes him independently wealthy some day. Bart can be reached at bishop@mcwoodpub.com.

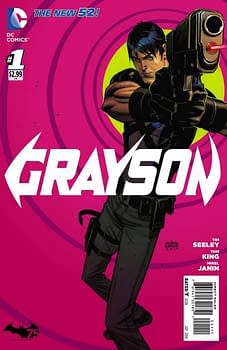

6. Grayson #1 (DC Comics, $2.99)

By Graig Kent

Through the reboot, Batman went relatively unscathed; de-aged to fit in with The New 52's 5-year-later starting point, sure, but otherwise maintaining much of the status quo, including having Damian as the active Robin. But with this decision, the extended Batman family got the short shrift, notably Stephanie Brown, Tim Drake and, yes, Dick Grayson. Steph was written out of the universe altogether (until recently), while Tim and Dick were ostensibly short-lived sidekicks thrust into the New 52 as their own men without meaningfully addressing to a theoretically new audience how their histories with Bruce Wayne affected them. In a sense, in not showing Tim and Dick as Batman's protege, it's as if they haven't truly earned their bona fides as superheroes. With Tim it was a washing away of his entire 20-years of character growth, but with Dick it was largely ignoring 40 years of being a sidekick, plus 10 years of finding his own way as leader of the Teen Titans and another 20 years of developing his own identity as Nightwing, as well as the occasional stopover as replacement Batman. Being Nightwing for Dick in the New 52 didn't mean nearly as much as it did before.

With recent events in Forever Evil, Nightwing was exposed to the public as Dick Grayson before being sacrificed for some plot point or another (I didn't read the event so I can't truly comment on it). Dick's progress from circus performer to sidekick to superhero to martyr is on display in an efficient one page beatnik poetry breakdown at the start of his new series, Grayson, which sees him resurrected as a superspy. Like so many of DC's character decisions in the New 52, this shift is a questionable one, in principle, seeming ill-conceived for the character. But unlike those rough early goings, writer Tim Seeley of Hack/Slash fame (with novelist and ex-CIA agent Tom King on story assist) seems to have a handle on what this shift means for Dick, with a well reasoned motive for it, and will hopefully have the liberty to explore it all.

This first issue begins with Dick already in the field, out on his first mission as an agent of Spyral, the shadowy organization first introduced in Batman Incorporated. The agency is collecting meta bio-weaponry under the guise of protecting the public, but their true intentions are as clear as the blurred face of its founder Mister Minos. This leads Dick out to collect a Russian man acting as mule for a bio-weapon only to find that Russian secret service are also in play (this largely takes place on -or on top of- a train, no less, in classic espionage fashion). Once Dick extracts his man, with the help of his partner Helena Bertinelli no less, he encounters a third-party, by way of a certain member of Stormwatch, making for a ripping good fight sequence.

What I was hesitant about with Dick heading into the role of superspy was DC feeling the need to turn the character into a brooding, lost Jason Bourne-like figure in order to have a espionage book in roster. Thankfully, Seeley seems keen on embracing Dick's Roger Moore-as-Bond personality and holding his position as goodwill ambassador to the DCU, even if he's doing it in secret. Dick, being one of the DCU's longest serving characters, but also having served as both a junior and senior member of its community, is utterly entrenched in its superheroing world, and to remove him from it would have been dire. Seeley wisely brings in all sort of DC Universe touch points in this first issue, and one quickly gets the sense that he's just as integrated in the Universe as he ever was, just in a different capacity.

Artist Mikel Janin was one of the brightest spots of the New 52 artistic roster working on Justice League Dark, managing to uphold the darkness of the title without overwhelming the book with it. He seemed exceptionally at home in the world of magic, making conjuring and mystical effects erupt dynamically on a static page. Here, Janin maintains the dynamism of his previous work, but in a whole different context. As a trained acrobat Dick Grayson is an inherently physical figure and Janin employs that sense of movement through Sterenko-esque perspectives and panel-border defiance. His page layouts stay conventional when progressing the plot or character moments, but those pages where the action ramps up showcase his creativity and skill in leading the eye. As well, Janin doesn't abandon the time-honored tradition of showing Dick's physical progression in a single panel, which has been a staple since Scott McDaniel's early days on Nightwing.

Beyond the motion, Janin gets the sex appeal of both the spy genre and Dick Grayson, and he delivers for ladies and gentlemen. His Dick Grayson is about as sexy as he ever has been, utterly handsome without being cloned from still photos of a celebrity or model. Janin's ability to deliver on this front should go a long way in selling this title to wary fans who prefer to see him taut in spandex.

Fans at large are casting a wary eye on almost every decision DC makes at this point, but editorial slowly seem to be making headway at winning old fans over and bringing them back in the fold with wiser decision making. Grayson is a promising fresh start for the character that is more fitting to the original intent of the New 52 than most of the titles that came out at the time. It's not perfect, but it is promising, and more importantly, entertaining.

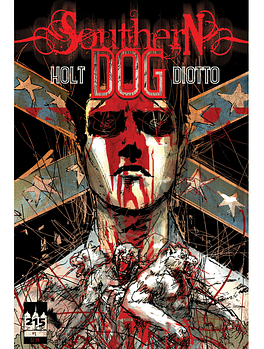

7. Southern Dog #1 (Action Lab, $3.99)

By Cat Taylor

There are basically two reasons why I decided to check out this book. First, it has some pretty compelling cover art by Riley Rossmo. I would describe it but a picture speaks louder than words. Just take a look at the cover image that accompanies this review and see if you agree. Unfortunately, in this case you really can't judge a book by the cover because the interior art was done by a completely different artist named Alex Diotto. He's not a bad artist himself but his work just doesn't measure up to the cover image. Even though he competently handles action, backgrounds, characters, action, panel layouts, etc., he has what I've come to think of as an "indie house style" that doesn't really stand out from hundreds of other decent independent comic artists who seem to intentionally make everything look a little sketchy and unfinished.

The second thing that piqued my interest was the publicity blurb stating that Southern Dog is a werewolf book set in the Deep South. I knew a plot like that was going to be a big hit or a big miss. If I got what I was hoping for I'd be reading something with a 1970s drive-in movie feeling or something akin to Near Dark or From Dusk to Dawn but with werewolves instead of vampires. After all, werewolves are still the least utilized of the well-known monster archetypes and a Deep South setting would likely add to the horror by being depicted as a primitive and isolated environment lacking in the most modern technologies. Plus, country folk can be pretty scary. Take Texas Chainsaw Massacre for instance. On the other hand, my pessimistic side could also see such a plot being an unoriginal and heavy-handed "Rednecks are racist and that's bad" story, unsubtly using werewolves as another "race" being victimized by the "real monsters." Unfortunately, this comic is very strongly that second camp.

The characters in Southern Dog are extremely one—dimensional stereotypes. The protagonist, Jasper, and one of his professors are the only non-racist white people in the book and wouldn't you know that Jasper has a crush on a black girl so that the writer, Jimmy Holt, could have the opportunity to show some racist black kids too. Pretty much every other character in this issue is a stereotypical racist redneck. Also, while this is only the first issue, there is very little werewolf in this werewolf comic. The brief moments that werewolves are featured, it's primarily to use them as a not-so-subtle substitute for minorities that the rednecks hate. Not only is this comparison as subtle as a sledgehammer, but it seems to serve little purpose since the people who hate the werewolves also hate black people. So, there's not even a "Oh, we're just as bad for hating werewolves as the Klansmen are for hating black people" moment. About the only thing that isn't an overused cliché in this story is that the werewolves can actually be killed by conventional means rather than being immune to everything except silver.

Even though I've given Holt a pretty bad pasting for this issue, in his defense I should point out that from the photo in his bio it appears he may be a minority also. So, he may have experienced a lot of racism growing up and this story may have been a very personal outlet for him. In addition, he was pretty young when he wrote this and everyone has to start somewhere. Sometimes it takes a little more experience to develop an original voice. I know that Holt has written some other comics but I haven't had the opportunity to read any of his other work.

Regardless, the first issue of Southern Dog didn't fulfill my hopes for a good werewolf comic. As a morality lesson, the comic is too heavy-handed and lacks the subtlety and thought-provoking content necessary to create any "oh wow, I never thought of it that way" moments that make morality tales effective. I hope that the comic will take a more interesting turn as the werewolves start playing a bigger part. The pieces are all there. They just need to be better assembled.

8. Spread #1 (Image, $3.50)

By Jeb D.

The setup's fairly straightforward: in a world visited by a monstrous plague that turns humans into ravening tentacle monsters, those few resistant are living the familiar survivalist lifestyle while trying not to be ripped to shreds by their one-time fellow humans. Our protagonist's name is No (he says that a lot when challenged), and his story is being narrated in retrospect by Hope, who appears to be the grown-up version of the baby that we see him take under his wing.

In these sorts of scenarios, it's common to spend extended time with a tightly focused group of survivors (The Walking Dead being the obvious current example), with only small glimpses of whatever might be functioning or changing in the larger society out there. Jordan has indicated that he's more interested in exploring those societal developments—"I've never been as interested in the first days of a zombie apocalypse as in what the world would look like ten or twenty years later"—and he dots the environment with evidence of that larger world, and the fact that we seem to be listening to a Hope who lived long enough to reflect back on these days suggests that he's got a good long-form plan to develop this.

Artist Kyle Straham, with suitably sanguine color from Felipe Sobrero, brings the requisite blood n guts; his style is cartoony enough that the monstrous creatures feel more absurdly grotesque than scary, with their flailing limbs and ravenous mouths on stalks (they look like Ralph Steadman's version of Alien), and his action paneling is sharp and snappy. No's resemblance to Wolverine is heightened by things like having him interrupt an arrow mid-flight by cleaving it in two with an axe, but Straham gives him enough emotional range, in both his face and body language, that Jordan can keep the hard-boiled clichés to a minimum. Jordan and Straham are playing a long game here, but I suspect if you can hang with the more derivative aspects of the narrative, they'll offer an interesting payoff down the road.

Jeb D. is a boring old married guy whose comics background includes attending the very first San Diego Comic-Con, being lectured on Doc Savage by Jim Steranko, and fetching an ashtray for Jack Kirby. After a quarter-century in the music biz, he pursues more sedate activities these days, and will certainly have a blog or Facebook account or some such thing one day.