Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates, san diego comic con | Tagged: bradford wright, carol tilley, censorship, Comics, Diagram for Delinquents, entertainment, Frederic Wertham, Jeff Trexler, neal adams, Praveen Kambam, Robert Emmons, san diego comic con, Seduction of the Innocent, Vasilis Pozios

Sixty Years Of Seduction – Right, Wrong, Rage, And Wertham At San Diego Comic Con

By Nikolai Fomich

[Dr. Frederic Wertham]

On Friday at San Diego Comic Con, lawyer and comics journalist Jeff Trexler (The Beat, The Comics Journal) moderated the panel "Sixty Years of Seduction: Right, Wrong, and Wertham." On hand to discuss Dr. Frederic Wertham and his surprisingly complex legacy were documentary filmmaker and professor Robert A. Emmons Jr., director of the new film on Wertham Diagram for Delinquents, history professor Bradford W. Wright, author of Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America, librarian and professor Carol Tilley, whose research into Wertham's methodology proved that his work on comics was scientifically unsubstantiated, and forensic psychiatrists Dr. Praveen R. Kambam and Dr. Vasilis K. Pozios, who serve as mental health consultants for entertainment industries through their organization Broadcast Thought.

Trexler opened the hour by welcoming attendees and explaining that "our panel "Sixty Years of Seduction" is not actually on how to – it is a panel discussion on the sixtieth anniversary of the publication of everybody's favorite book, Seduction of the Innocent." He went on to explain that "we're going to talk about…what Wertham has meant to the comics community and his ongoing impact on culture today, and whether or not he deserves his reputation."

[Our Host and Panelists: Trexler, Emmons, Wright, Tilley, Kambam, and Pozios]

The Dedicated Political Liberal – Whose Ethics Lapsed: On Wertham's Complexity

Though reviled throughout the comic book industry because of his crusade against comics in the 1950's, Wertham was in reality much more than a feverish mastermind bent on annihilating funny-books. To introduce Wertham the man to an audience more likely familiar with Wertham the cartoon, Emmons recounted how his own ideas on the infamous psychiatrist evolved and how that understanding motivated him to create Diagram for Delinquents. "I teach media studies, typically audience studies, so I've always been interested in media effects and media responsibility," Emmons began. "I've been a comics reader as long as I could read, so I had knowledge of Wertham like many comics readers had – this guy ruined comics. I thought about him for many, many years, and [eventually began] thinking about the possibility of making a film about him. And so when the Library of Congress made his archives available to the public three years ago, I thought, "Now is the right time." In preparation to make the film, I started reading what was out there. And as I did the figure of Wertham started to become a lot more complex for me, from what I had previously known as this guy who ruined comic books. One book in particular was Bart Beaty's work on Frederic Wertham and mass culture and mass communication – [that and] other books really started to complicate things."

Unlike previous accounts, Emmons hopes to not only show a more nuanced portrayal of Wertham in his film, but also place him firmly in his socio-historical context. "When I would see other documentaries about comic books, everything from Comic Book Confidential to Comic Book Superheroes Unmasked to Comic Books Unbound to the PBS series, they all seemed to have the same perspective on Wertham – the psychiatrist who wrote Seduction of the Innocent, who said that comic books caused juvenile delinquency – which is not necessarily the case in its entirety. And it was always the same two minutes, the same exact footage. It didn't really get into the context of the entire historical scenario. So I thought it deserved to be covered in its historical context, not just [focusing on] Wertham, but on what was going on in America at the time – socially, economically, and culturally – and how all of these factors allowed this shift in comics."

Emmons explained that while he isn't in any way a Wertham apologist, he thinks the psychiatrist's other achievements – such as his founding of Harlem's LaFargue Clinic, the first psychiatric hospital which treated African Americans in New York – shouldn't be swept under the rug. "Wertham did play a big role and was indeed probably the loudest voice against comics. There's no doubt that the man hated comics as much as one could hate comics. But this is a man who had done a lot of extraordinary things. His stand on violence and anti-violence [was extraordinary] and he said some extremely brave things in A Sign for Cain about the capacity of society to negate violence. He's this guy who was a contradiction, someone who had a very high social ethic but whose ethics lapsed in some ways because of his extreme fanaticism about comics. What I wanted to do was show as much as I could the whole story, in an effort to give as complete and holistic an image of this individual [as possible], and then let comic readers like myself make a decision for themselves. It's all a part of the contradiction of Wertham and his political views, and why it's so hard to understand how on the one hand he seems to be this one guy, and in another sense he seems to be this other."

Several clips from Diagram for Delinquents were shown to the audience, including one in which Bart Beaty elaborated upon Wertham's extraordinary beliefs regarding violence: "He believes very, very forcefully that human violence is something that can be ended. He didn't believe that violence was an innate aspect of the human personality. He felt that it was a learned trait and that we could eventually eradicate violence, that we could teach children not to be violent, we could teach therefore adults not to be violent. So anything that contributed to the minimization of violence was a good thing, and anything that contributed to the desensitization of violence in his mind was a bad thing, and could lead to increased hostilities around the world."

"And from the mid-40's to the mid-50's that violence was comics," said Emmons, "and that's why we're here."

"One of the things that I think makes Robert's documentary so valuable is that it's not just a cartoon picture of Frederic Wertham," added Trexler. "We may not agree with what he had to say, but he really did have earnest motives that may have led him astray. I'm a lawyer, and one of the things he's known for in the legal community outside of comics is his research that was crucial to a decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which [helped] end segregation in the United States. So it's a very complex dynamic of motive."

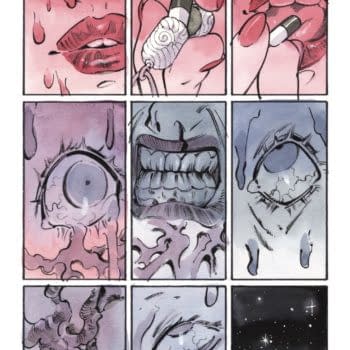

[Diagram for Delinquents]

A Celebration Of Consumer Choice – Except For Children: On Wertham's Social Context

Though Dr. Wertham has become symbolic for the hysteria that many believe almost destroyed the comic book industry, Wright said that in order to understand how this hysteria originated we must look at "American culture in the post-war years" as much as Wertham himself. "I wrote a history of the comic book industry in the context of American culture and history, and I was trying to look at these changes and how they affected [comics]. This was a time coming right out of World War Two, and [there was] a lot of concern with propaganda – propaganda that could be used for fascist ends, and during the Cold War years, communist ends. There was a sense that things were spinning out of America's control, and people were looking for any evidence of subversion or for these kinds of mysterious forces that were working against the American family and American values. [By] fixating on a particular culprit that could be attacked by parents and parents groups, as opposed to looking at all the complexities underlying the social and cultural changes, Wertham discovered that you could focus on…something that every parent could understand. And even if he sometimes acknowledged that this [was only] one contributing factor, he hammered away at comics so much that [attacking comics] came to be seen by parents as 'the one way we can fix it, the silver bullet we can focus on.'"

In addition to concerns over propaganda, another major cause of anxiety for parents in the 1950's was the shifts occurring in children's culture. "I don't think anyone here wants to be an apologist for Wertham, but we have to keep in mind too that children's culture at this time in the 1950's meant something very different than it does to us today. There was still this idea that children were innocent and were supposed to have this separate innocent culture, that the adult world and adult sensibilities and complexities were not supposed to intrude upon too much. We're used to quite the opposite – this convention is evidence of how childhood fantasy and adult sensibilities have blurred so much. They're kind of meaningless now. But in the 1950's there was still this idea that you could put out a gangster film or a horror movie for adults, but putting that into the area of something that – in most people's minds – was firmly for children…that's what caused so much of the uproar, and gave Wertham such a huge audience.

"What was happening at the time was that there was this revolution occurring in children's culture – children were becoming more independent consumers. And even though the trend in the 1950's was very much to celebrate consumption and consumer choice as part of the American Way, the American way of life, a lot of people weren't ready to give children that kind of choice, especially when they were choosing images and scenarios that were so negative and hostile to the American Dream. They hadn't really discovered irony yet in the 1950's the way we have [Laughter]. We look back at a lot of those comic books Wertham and the senators were discussing and we see the humor, especially in the EC Comics. For them it was – "Comics – not so funny.'"

Trexler said in response that "the power of that title I think is something we forget today – Seduction of the Innocent. The notion that children are innocent is lost for many of us. And further, Seduction of the Innocent calls back to the Garden of Eden – it's the fall from grace into these comic books. So he's addressing a major cultural shift that a number of people there found very baffling, in a way that was very popular at the time – through psychiatry, what they understood to be science."

"I Want You To Rip Him A New Fucking Asshole": On Wertham's Effect

Yet in spite of benign motivations and a complex sociological context, for actual comic book fans and creators both then and today Wertham only rouses vitriol. Asked by Trexler about Wertham's "broader cultural legacy and the response to him in the comic book industry," Tilley responded by relaying the opinion of one of comicdom's greatest artists on the infamous doctor. "I suspect most of you know that Neal Adams speaks his mind quite frankly," Tilley said. "I spoke with him in Chicago earlier this year and we were talking a little about my work. I was saying my goodbyes and walking away from his table when he called after me. He asked, "So are you going to write more about Wertham?" I said, "I think so." And he [replied], "Well I want you to rip him a new fucking asshole." [Laughter] I asked, "Can I quote you on that Mr. Adams?", and he said, "Please do."

"I am coming at this as a librarian and as an information historian," Tilley said. "I really didn't care about Wertham – I really thought that everything that needed to be said about Wertham had been said, and my own research into his archival materials wasn't motivated by any interest in him. I was going because I am interested in kids' comics reading and librarians' attitudes and educators' attitudes [toward that]. I went to look at the papers because he refers to these librarians and teachers who he had heard from, and I wanted to see these fantastic letters that he implied he had. I didn't find those, but along the way and very quickly I realized there were lots of other things going on in the papers." What she discovered was that Wertham repeatedly exaggerated and even fabricated much of the evidence in Seduction of the Innocent, as widely reported last year.

Tilley explained that Wertham is partially responsible for comics' ongoing reputation as "kids' stuff" – and the resulting reaction from serious comics readers to prove otherwise. "We're still seeing within librarianship and in the education community at all levels – K-12, higher education – this notion that comics are lesser than. And I think we see this to some extent still in comic scholarship – there is still a reticence to address comics reading from a child's perspective, to think about youth culture and comics reading historically, because we're still trying to prove to the world that comics more than kids' stuff."

As for comics readers who lived through the 1950's and are alive today, they all seem to share in Neal Adams' opinion. "I've been uncovering letters from kids who wrote to Wertham around the time Seduction came out, kids who wrote to the US Senate during the 1954 hearings," Tilley said. "I have been able to contact some of these kids who are now in their seventies and talk to them. And one of the things that really stood out to me is how pissed off they all still are! [Laughter] These are folks who have grown up to be attorneys and college professors and entertainers and writers, and to a tee they all still think that Wertham was a horrible person. One of these folks is a retired history professor here in California. He told me after my paper came out, "You know even Hitler was nice sometimes." Even from his perspective as a historian, he thought I had gone much too easy on Wertham."

[EC Comics (Image Source)]

Trexler noted that "[the idea that] comics are just kids' stuff is something that has persisted decades later" and that similar thinking is now applied today "to a number of other kinds of media." He also said Tilley "brought up an interesting connection – that a number of people who read comics in '50s became lawyers. [Laughter] Maybe it proves he was right. I don't know."

Correlation – Not Causation: On Wertham's Theories

But beyond the dubious nature of Wertham's research into the effects of comic books on juvenile delinquency, the broader questions and concerns he raised aren't as easily dismissed. Trexler asked Doctors Kambam and Pozios what psychiatrists today think "about media's influence on human behavior and particularly on criminality."

Kambam began by contextualizing Wertham's thinking, explaining the trends in psychology sixty years ago. "As Carol uncovered, the methodology was awful from anybody's perspective," Kambam said. "But looking at it from a theoretical perspective, [looking at] the arguments, I think it's important to note that he was living in a time when psychoanalysis was the big dog – Freudian type of stuff. You all probably remember from psychology or biology classes the age old debate – nature versus nurture. So in mental health or in psychology or psychiatry, [the question was] "is it your biology or is it your psychology?" And today that's meaningless, because it's blended together. There isn't that distinction. But at the time those were the waves that went back and forth. As Robert's clip showed, Wertham strongly emphasized the environmental influence on folks. [Robert] can probably speak better to this than I can, but it seemed like he wanted the environment to be an explanation for delinquency, and it's interesting because he was also an advocate for under-privileged youth. He founded the LaFargue Clinic in Harlem that he was working at. From an advocacy perspective, it would be a lot nicer for us to say, you know what, it's the environment that created this criminality or delinquency, it's not the person – it has nothing to do with their sex, their ethnicity, this kind of circumstance. It's interesting to contextualize it that way."

"He actually extenuates that point at the very end of the book on the last page," Pozios added, "where he [speaks to] a child's mother who's worried that did she do something wrong. He reassures her that she didn't, that it was the comic books."

[Seduction of the Innocent]

"The only other comment I'd make about the past to contextualize Wertham is that a lot of the papers that were put out then actually used these theoretical observational [kinds of reasoning]," said Kambam. "One of his influences was Kraepelin. Kraepelin was a psychiatrist who, among other things for which he's famous, observed people that were in asylums. And he noted just from observing people that there were two patterns, now called schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, which we actually use today."

The discussion turned to the complex relationship between violent media and violent behavior, Pozios providing a modern psychiatric perspective to help us understand this thorny issue. "To address the age old question, "Does media cause violence?" I think we have to think about [whether] that is the proper question to ask," said Pozios. "We approach violence from a public health perspective, and actually Wertham does too in the book. Just like we would examine risk for things like heart attacks or cancer, we also research and examine what the risk factors are for violence. And we know what some of these are – male sex, low IQ, a history of violence, etc. And these risk factors contribute to your risk of violence over time. The general consensus in the media violence research is that there is a small to moderate correlation between violent media and things like aggression – both verbal and physical – and that correlation has a small to moderate effect size. There's some relationship there, but how big a link is it – how big in effect is media violence on actual violence? There are [also] things that we have to take into consideration that we may not have answers to. For example, what sorts of factors mitigate the risk of media on the risk for violence? We don't know that."

"I'd just add one thing," Kambam said. "It is also important to ask who is particularly vulnerable. So say [for] a heart attack – if I have a genetic history, I'm particularly vulnerable right? One thing Wertham was concerned about was whether children were particularly vulnerable [to violent media]."

"Right, and we don't have an answer for who's particularly vulnerable to things they might see in television or film or video games," said Pozios. "But to ask that question, "Does media cause violence?" – whether it be comic books or television or [whatever] – it's the wrong question to be asked. There's not that simple, clean causal link. It's a multifactorial issue, and it's entirely possible that violent media is a part of the pie. But that slice is probably pretty small. Some people argue that it's something that you can control –you can always turn off the DVD player, or what have you. People think that this is something you can at least modify as a risk factor."

"If I could just jump in, you used a really important word when you said "correlation,"" said Emmons, "which a lot of people confuse in a couple of studies with causation. They're not the same thing, and I think that's a confusion that happens when looking at media effects in media studies. I think it's very important to make that distinction, that one does not lead to the other."

Setting In Motion A Line Of Logic: Wertham The Censor?

Pozios observed that while many other issues in comics raise serious concern among fans, violence seems to be its own beast, something thought of very differently. "I think what is particularly interesting when it comes to comic books is that when the issue of violence comes up – and people automatically start talking about Wertham of course – there are a host of other issues that are not perhaps treated in the same way as violence. Violence is always a very black and white, all or nothing kind of issue. Does media cause violence? It's either yes or no, it's never any in between kind of answer."

"And it's not just casual violence," said Kambam, "it's extreme acts of violence."

"Correct. When you talk about violence, people in their mind often picture a mass shooting, for example, or something terrible like that, and of course that leads to, "What do [we] do about that, what's the solution?" Pozios said. "Wertham wanted to prohibit children from purchasing comic books, and [the question becomes], "Is that censorship? Is the comics code censorship?" Well, what is censorship? There are certainly some recent examples of what I think are legitimate concerns about what is portrayed in media, and particularly for this audience in comic books. When it comes to portrayals of ethnic minorities, the objectification of women in comics, there're certainly a lot of very legitimate concerns about that, and calls to creators to be more mindful of how things are portrayed. Is that censorship? I don't know, maybe it is. But it seems to be more tolerated than calls for concerns about portrayals of violence. So it's interesting that violence is always a separate animal when it comes to media and the issue of what is acceptable."

[Seal of – Censorship?]

"You all raised some very interesting questions and very interesting points about the nature of censorship and also contextualized how Wertham saw himself versus how we see him," said Trexler. "For example, we don't think a lot about this now, but you mentioned Hitler earlier, and we think of Hitler as his own person, a particular instance of evil. But he was actually riffing off of a very popular theory in the United States at the time called eugenics, which [suggested] that in whole ethnic groups criminality and corruption were basically passed down through inheritance. And so with Wertham we have a reaction against eugenics, and you also have a reaction against American racism, which saw an inferiority based on the color of one's skin. And [he's] saying, "No look, criminality doesn't happen because people are black, criminality doesn't happen because these people are genetically corrupt – there are other influences." Now again, I'm not saying that everything he thought was right. There was this weird conceptualization that was going on, and it raises the question of censorship. And before I open this up to the whole group, I know Robert has a really excellent piece from his documentary about whether Wertham did see himself as a censor."

"This [clip] addresses the notion of whether Wertham was a censor," said Emmons. "He had actually done a lot of work in freedom of speech, testifying in court to prevent censorship. Not many people know this. In this clip you'll see Charles Brownstein, the executive director of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, who looks at the lasting legacy that has really transcended what Wertham had done in this period and what he's come to stand for." In addition to Brownstein, the clip featured Amy K. Nyberg, author of Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code and James E. Reibman, a biographer of Wertham.

Nyberg: "Wertham's goal was actually just to prohibit the sale of comic books to children under a certain age. He was not interested in these making of lists of good or bad comics, he was not interested in necessarily adopting codes for comics – he simply just wanted to ban the sale of them to children."

Reibman: "There's the allegation that Wertham was a censor. That is not true. Wertham believed that protection of children was a public health issue. If you are an absolutist in terms of civil liberties, or free speech, I guess you could argue that. But we don't have absolute free speech, I hate to pull out the hoary dicta of Oliver Wendell Holmes – but it's probably appropriate – "You can't yell fire in a crowded theater." There are limitations on what free speech is. Wertham was a progressive, and he believed in free speech. He said children are a special class that need to be protected."

Brownstein: "And so Wertham, whether he intended to be a censor or not, set in motion a line of logic that led to censorship, and set in motion a line of thinking that made him an icon of censorship."

"With All These People Studying All This Media Violence…": Questions From The Audience

"You can see a very complex, contested legacy," Trexler said. "There are interesting tensions and also resonances with what he said [and did] and how we see things today." Trexler opened the floor to questions, reassuring the audience "[not to] worry. I know some of you may be hesitant to say something negative about Wertham, but don't be afraid. [Laughter] We're open to all points of views."

The first question was about the invention of childhood and whether any children were not included for Wertham as children, since "poor children were not included as children" in earlier times.

"I think most of Wertham's research was with a lot of poor children, but as I recall he would make the point that children who would come from "broken homes" or "difficult homes" or some sort of social dislocation were maybe more susceptible to the kind of violent images and immorality that were in comic books," said Wright. "But even those children who came from "well-adjusted" – in his terms –families and homes, even…well-adjusted, middle class suburban kids [were susceptible to] the bombarding of violent images and the way violence came to [be seen] as a normal solution in comic books. I think it's important to remember too that America was really on the move at this time. This is the huge expansion of suburbs across the country. There had been a lot of families that were uprooted, dislocated families that had perhaps been already broken or challenged by the war years, so there are a lot of complicated social-cultural factors. But Wertham – I think he said at one point that it's easier to get rid of comic books than it is to bulldoze the slums. So let's go after the comic books, worry about the slums later."

"And then look what happened," said Trexler. [Laughter]

"I would add really quickly that almost all of the kids whose case files that I examined for my work were lower and lower-middle class," said Tilley. "There were a few middle and upper class kids, but those tended not to be kids that he was treating. Those tended to be kids other folks brought to him, as anecdotes."

Another audience member wondered whether the shift from "realistic murder comic books" to powerful superheroes was a reaction against Wertham's campaign, and perhaps a way for comics to "create distance from regular violence."

"They were trying to expand their audience," explained Wright. "They got a lot of adult readers during the war years, a lot of G.I.'s overseas, and superhero stories were running out of ideas right after the war. So they found these new genres to exploit, like comic book versions of gangster films for a while, and later on horror comics. They were trying to expand into areas even Hollywood film sometimes would not go in."

"Actually I wanted to add to what Bradford said," said Pozios. "You mentioned Hollywood films, and Wertham mentioned a concern about violence in film. I think he had the opinion– at least in Seduction of the Innocent –that the jury was sort of still out on TV, [and he adopted] a wait and see approach."

"He eventually got to it," said Emmons.

"He was concerned with comics because they were portable," Pozios continued. "Back in the day they didn't have DVDs, they didn't have iTunes, and children – according to Wertham – would pass along comics, and it was something almost viral, the violence and the imitative violence that was maybe associated with that. So although he commented on violence in the larger media, that's [why] I think why his focus was on comics."

"And the sheer exposure – the amount of children that read comics, as both Carol and Bradford know – we're talking over 90% of children at this time," said Emmons.

The next to comment from the audience was comics scholar Peter Coogan, co-founder and co-chair of the Comics Arts Conference. Coogan said that he had invited Neal Adams years ago to participate in a conference but that Adams said no, telling Coogan that "I want to keep comics low to the ground." Coogan explained that "Wertham was the model of the academic doing comic scholarship in the field" and that "there's a whole generation of professionals who didn't want to talk to us. They didn't want those who have PhDs to have any interest in comics whatsoever." He went on to explain that a few years ago members of the Comics Arts Conference were planning a panel on Fables. Bill Willingham found out and was unhappy at first, but attended the panel and afterwards invited them to a party. "So it's kind of working its way out, but that's in fact a Wertham influence on comic scholarship."

"I do want to mention quickly that there were comics creators who gave Wertham information, who told him that their business was corrupt, and that someone needed to step in," said Tilley.

"One of them was Jerry Siegel," added Trexler, "who had severe problems with the comics industry at that point."

The next question came from an audience member who said that "when I think of the comics that I read and enjoy today, the vast majority of comics I would not give to young kids." He asked whether "anyone would care to answer if Wertham was right?"

[Comics for Kids!]

"I often say [this to] people when I talk about this," responded Emmons. "You see the comics he was talking about. There is no way I would let my daughters read these comic books. But it is my responsibility to take care of that issue. So I guess the question, "Was he right? Should they have been sold to children under sixteen?" That's not his decision to make, that's my decision as a parent."

"I wanted to point out that – and this is my background as a librarian, which is very free speech oriented… – we know that books can be used for good purposes, they have good effects, which means they can also be used for bad," said Tilley. "But I think the problem is we don't know what is going to trigger what. We don't know the response or the reaction a particular text is going to have on a particular reader."

Pozios suggested that the question of whether Wertham was right was probably the wrong one to ask. "I would start with the question that you asked, "Was Wertham right?", and I think one of reasons why we titled the talk as we did was because we always think of Wertham and [ask whether] he right or wrong. That's an artifact of this black and white, all or nothing thinking that we have on this issue. I'm not sure that that's the right question we should be asking. We should be looking at the information as whole and making our own conclusions without making these judgments. Are there causes to be concerned about media violence? I think the answer is yes. Is it something to be overly concerned about? The answer is probably no. In the future, will we have a better idea of what sort of media affects what sort of person? The answer is hopefully yes. And what do we do about it? Well, like Carol said, she said she's an advocate of free speech. We live in country where freedom of speech is one of our constitutional rights. If we ultimately find out that some aspect of violence in media causes some form of violence in real life, should we do something about it? The answer is maybe not. It's our right to determine how we want to handle that."

The following audience member asked whether "Wertham [believed] there was ever any acceptable cause for violence," like "violence to prevent further war."

"He didn't believe in violence," Emmons replied. "In reactions to situations of war like you were saying, I would say no, and that he wanted to move towards an anti-violent society. To most people – this is why I appreciate that thought he had – it seems crazy. You can't fathom it. Some people think violence is part of human nature. He did not. [He thought that] this is a learned trait, and that we could unlearn this and become peaceful, sustainable. That sounds utopian, and in a way it is, but if you think about systems of ethics, [Descartes'] First Philosophy, this is of the highest order. So I feel that it's an extremely brave way of thinking."

[Wertham on Violence]

My own question followed. I asked about Wertham's dual life as a committed public intellectual in his early career and as a talking head on television in his later life, and why that shift occurred.

"Wertham recognized the power in his ability to seize the media to address these issues of media problems," said Emmons.

"He used the same sensationalism that he accused comic books of exploiting," Wright explained. "He said, "A fourteen year old boy and fifteen year old boy kidnapped an eighteen year old girl and raped her." It gets everyone's attention, and he goes on in detailing all these horrific sundry episodes. So yeah, he is a figure of popular culture as much as he is a critic of it."

The next question was about Wertham's methodology, and whether the "forensic psychologists [could] comment on that methodology and whether it was valid."

"I actually see a lot of juvenile delinquents for court evaluations, so I can speak to that," said Kambam. "The problem with a lot the arguments that get put out on media violence…is that there're so many variables. It's incredibly complicating, even for us predicting violence. So it's not that convincing to me when people say, "OK, there is more violent media happening, but the overall rates of very violent crime went down." But that's one variable out of the multiple variables out there. It would be like saying, "OK, we have a little bit lower smoking rates, so how come there's all of the sudden more heart disease?" Well people gained more weight. There're other factors going on, so I don't think you can just look at the one factor. And if you take it in that sort of way, try to approach the issue in that way, you're just going to be wrong. The best way we have now – which isn't perfect either – is looking at it from a public health perspective, [which is] a much more multifactorial process. Maybe one day we'll be better at getting all these variables and weighing them."

"But Wertham actually said he was trying to do that," Tilley added. "He said that he was trying to look at kids holistically. He was trying to look at society holistically. And yet… He achieved that in the book that followed Seduction of the Innocent. He did this beautiful case study of this kid who was on trial for murder. But he failed to do that in Seduction of the Innocent."

The final question expressed sincere concern for the panelists themselves: "With all these people studying all this media violence, should we be concerned that they're all going to turn into rapists and murderers? With that kind of repeated exposure…" [Great Laughter]

"Fortunately we have a few protective factors," said Pozios.

"Either that or lawyers," quipped Trexler.

It was an excellent panel, its success lying both in its diverse range of truly knowledgeable panelists and in Jeff Trexler's uncanny ability to so easily moderate a group of five experts, each with so much to say. Having attended my fair share of panels which floundered because of poor moderation, I hope to see Jeff continue to host many panels in the years to come.

Yet for all the complexities the panelists introduced, I believe Wertham will forever remain a symbol among comic book fans of an ignorant, judgmental, and potentially dangerous mainstream – unwilling or unable to see the value in comics like we do. It's a sad legacy for a progressive pioneer like Wertham to be remembered by – and a cautionary tale for those who would follow in his footsteps.

Many thanks to Jeff Trexler, Robert Emmons, Bradford Wright, Carol Tilley, Praveen Kambam, Vasilis Pozios, Julian Darius and Mike Phillips from Sequart, Peter Coogan, and the audience members for a very special panel. Come back later this week when I interview Emmons about his new film, Diagram for Delinquents.