Posted in: Comics | Tagged: comic con, Comics, entertainment, new york, new york comic con, NYCC, nycc 2016, nycc16

Comics Master Class: Employing Narrative Captions

by Aldo Alvarez AKA Dale Lazarov

I have not read any in-depth writing on how narrative captions operate and how they operate well. (Let me know if you have in the comments section for this essay as I am eager to read what you have read about them.) Narrative captions went out of fashion the more comics tried to resemble moving image narrative and less like comics. Because of this "cinema/tv/gaming bias", captions have been stigmatized as a narrative cheat that well-dramatized comics best avoid. Also, captions are associated with genres not popular in capey comics culture, like Romance comics and autobiographical graphic novels, both which heavily depend on them. Given that I quickly burned out of having to slog through redundant, back-and-forth captions in the expositional narrative voices of Superman and Batman that meagerly represent how "different and yet the same" they are, I can understand why comics creators shy away from them.

I don't think that narrative captions are a narrative cheat; I think that when narrative captions are used as a cheat, they come off as a cheat. I'm particularly thinking of how Sex Criminals avoided dramatizing an emotional transition between the first story arc and second story arc by having its narrator abruptly describe a change in her boyfriend's commitment to crime that happened off the page between arcs. I was being told, as a reader, that a central issue with one of the protagonists had conveniently gone away…and it was the one I was most engaged in and wanted to see play out. It felt, given what I saw in the first volume, like "Note: Poochie died on the way back to his home planet" and the dramatic tension I was invested in was an inconvenience to the caper plot. And that's when I stopped reading Sex Criminals.

I know that it looks preposterous for an Astute Geek Elder Gay Latino Wizard known for comics without dialogue or captions to write a listicle about using narrative captions in comics. But I have thought about them quite a bit; it's my understanding that you have to know how traditional narrative technique works – what it does for a narrative form – before you choose to break the rules by not using it. Lately, I have been seeing new comics writers reviving the use of captions to impressive and emotional effect — like in Tom King's scripting for The Vision — so I have been revisiting my ideas about how and why narrative captions work.

Here are a few thoughts about how to employ narrative captions in comics. Note that these uses are not mutually exclusive; as you will see, you can combine them.

• At the very minimum, a caption serves as a transition between moments in a comic that don't have an immediate connection and would seem like an abrupt change of scene without them. Any caption that starts a new scene is a transitional caption: time and date captions, captions with dialogue in quotation marks at the end of a page that lead you to flipping the page to the next scene, "Meanwhile, back at The Carrier traveling through The Bleed", spring to mind as examples of this use of captions.

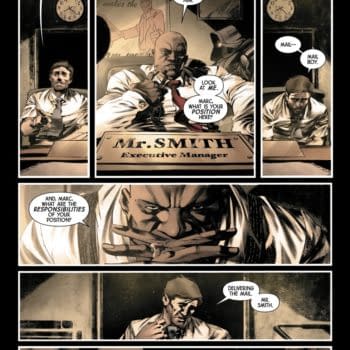

• Non-transitional narrative captions add a layer to the action or the moment being presented in the illustration. They don't reiterate what's been drawn; they add to the flow of the narrative that the image can't communicate by itself, like an action the reader is asked to imagine and expand on before the next moment happens. These captions use the illustration they're embedded with as a key moment or key example so you don't have to see page after page of Jimmy Olsen washing dishes in a fine restaurant's kitchen because he forgot he had to pay for his dinner date with Lucy Lane.

• At best, third person narrative captions are used to add nuance, texture and/or flavor to the story that is as immersive and evocative as the sequence of images. Both images and captions frame each other's meaning and bring about the experience of the narrative. Compare the flavor of these actual captions from The Authority with the deliberate flatness of my version of it in the first bullet point:

Caption one in a large title font: "THE CARRIER"

Caption two in traditional comics lettering: "Tacking into The Bleed, superposed channel between alternate universes…"

And I am swept up by the sci-fi poetry and spectacle of the moment and can't wait to read the scene that follows it. It doesn't need an exclamation mark to thrill me.

That nuance, texture and flavor in third person narration is primarily about giving the world of the story a "god" narrator who embodies the "personality" of the world. That god voice can be whimsical, awe-inspiring, frightening, or any narrative stance you can evoke with words. All stances work if the personality of the narration adds something to the narrative that makes it more engaging rather than alienating…unless alienating the audience from the story is the point of the narration.

• First person captions give an intimate experience of the person being represented visually because we get a sense of how they think and experience the world we're seeing. The texture and nuance is additive or contrapuntal with the image they frame and that addition or counterpoint is deliberately part of the story as a whole. I would argue that, in comics, as it is in Modernist literary narrative, first person captions are, at their best, also a narrative strand of its own, separate from the visual narrative, that's about understanding their internal and individual character as they engage with a material world of images and actions separate from it.

It's a missed opportunity if the first person narrative voice is just a convenient narrative vehicle and serves no purpose in understanding the person they represent through how they articulate their experience. This is why Rorschach's captions in Watchmen feel important for their own sake – as an expression of a personhood — and why grimdark first person captions feel like the expression of a style. This is why Alison Bechdel's captions in Fun Home, grasping at an understanding of her experience of her family and its remaining mysteries and uncertainty, are a counterpoint to the confident clarity and charming stylization of the images she renders to visualize her material past experience. In comparison, the captions in Marjane Satrapis' Persepolis come off perfunctory, about average memoir's self-justification.

• Ultimately, narrative captions are a storytelling tool. Forsaking them to be more like moving image narrative thwarts what comics can do as comics: represent both the subjective and objective experience of being human…and the subjective and objective experience of a sinister, immense interdimensional spaceship that looks like an awesome shark.

***

About The Author(s):

Aldo Alvarez, Ph.D. is the author of INTERESTING MONSTERS (Graywolf Press, 2001) and has an MFA in Creative Writing from Columbia University of the City of New York and a Ph.D in English from Binghamton University (SUNY). He's tenured faculty at Wilbur Wright College in Chicago and teaches writing, research, fiction, gay and lesbian literature, graphic novels and LGBT Studies. He was born and raised in Mayagüez, Puerto Rico, a shipping port and college town in the west of the island that received comics pamphlets, glossy comics magazines and comics hardcovers from all Spanish- and English-speaking countries. He also writes and art directs gay graphic novels as Dale Lazarov.

Dale Lazarov writes, art directs and licenses wordless, gay character-based, sex-positive graphic novels published under the Sticky Graphic Novels imprint: TIMBER (drawn by Player), SLY (drawn by mpMann), BULLDOGS (drawn by Chas Hunter & Si Arden), PARDNERS (drawn by Bo Revel), PEACOCK PUNKS (drawn and colored by Mauro Mariotti and Janos Janecki), FAST FRIENDS (drawn by Michael Broderick), GREEK LOVE (drawn by Adam Graphite), GOOD SPORTS (drawn by Alessio Slonimsky), NIGHTLIFE (drawn and colored by Bastian Jonsson and Yann Duminil), MANLY (drawn by Amy Colburn), and STICKY (drawn by Steve MacIsaac). Sticky Graphic Novels are published in hardcover by Bruno Gmünder GmbH and in digital format through Class Comics. In his secret identity, he is Aldo Alvarez, Ph.D. and he lives in Chicago. His website is at StickyGraphicNovels.com.