Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Comics, david hine, doug braithwaite, image, storm dogs

Gender, Sex Work And Going Beyond Diversity – Storm Dogs #5

Natalie Reed writes;

There's been a lot of trans characters popping up in comics these past few weeks.

Well… contextually "a lot", anyway. Contrary to some perceptions that the mainstream comics are being glutted with some kind of forced explosion of LGBT "tokens", the truth remains that the medium as a whole is still very much a heterosexual, cisgender (not trans), gender-binary kind of place. But in contrast to how things have gone for the past seventeen years or so, in which themes of gender diversity were only really explored allegorically, or through fantastic stand-ins like body-surfing evil geniuses, shapeshifting super-skrulls, memory-retaining reincarnations and futuristic miracle girly pills, this is the best we've had things in terms of trans representation since the all-too-brief days of comics like Sandman, Doom Patrol and Deathwish.

Not all representations of trans characters are equal, however. For every empowering character like Doom Patrol's Kate Godwin we get a crass and stereotyped caricature like Red Hood's Suzie Su. For every sweet and good-natured little sub-plot like Tong's in FF #4, we get some insulting gross-out moment like The Russian's depiction in Punisher Noir, and for everything that feels relatable, down-to-earth and well-researched like Batgirl's Alysia Yeoh, we get something over-the-top, wildly inaccurate and generally exploitative like Lord Fanny of The Invisibles.

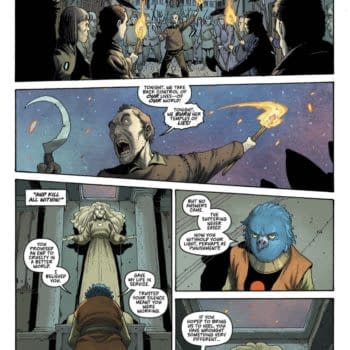

The latest instance of gender variant themes being employed in a major comic book (let's just go ahead and count Image as "major") is the character of Doll in David Hine and Doug Brathwaite's Storm Dogs, first introduced in last month's issue #4 and soon to receive a somewhat larger role in the book, at least in terms of its character dynamics if not its more sweeping and epic space opera elements, in issue #5, available this week. As is pretty much always the case when I come across cisgender writers tackling gender diversity, I was very, very much on guard, and expecting the worst, but I'm happy to say that thus far Storm Dogs has approached Doll's characterization, and the conflicts surrounding her, with a degree of nuance, specificity and complexity that is very rare, and impressive, to find in a medium where simply stuffing "I'm a girl on the inside!" cliches into your dialogue is somehow enough to be lauded as progressive.

Spoilers below.

Doll is a "wire", a futuristic sort of sex-worker in which an implant in her brain allows clients to, effectively, "be" her for a period of time (think Being John Malkovich). The service is explicitly described and treated as being sexual in nature, and the various "wires" have generally been modified in ways to make this experience more satisfying for the various kinks of differing clients (the reader is, for instance, also briefly introduced to a male wire named Cutter who has been augmented with technology to make him experience more pain, and heal faster, to appeal to masochists who wish to enjoy such activities without doing harm to their own bodies).

One of the series' principle characters, Jerod, employs Dolls' services, then grossly violates both her privacy and the boundaries of their professional terms by using his time in her to go through her personal belongings and research her life, developing a, perhaps misguided, "care" and "concern" for her. Even leaving aside the question of Doll's gender status, this is already to broach some very complex and meaningful questions of sex work, consent, the relationships clients may have towards sex workers, the lack of respect often demonstrated towards boundaries (paying to cross one boundary doesn't mean you get to cross whichever other boundaries you want), and misdirected feelings, of both love and a desire to "save", that often get projected onto the provider… all of these being issues that very much have relevance to our real world, and to the people who survive our world by making their living in the sex trade. Futuristic technologies aside, all of these things -boundaries, consent, respect- all matter here, today.

The questions Hine raises in regards to the particularities of Doll's gender, and how Jerod relates to it, are no less complex, and no less grounded in real world, present-day concerns.

One of the first things I appreciated about Doll was the way in which Doug Braithwaite designed her appearance. She's visibly feminine, and she certainly carries a palpable sexuality and beauty, but she's also visually identifiable as gender variant. Her facial features, for instance, are noticeably "masculine", with a strong jawline and clearly defined cheekbones, and she doesn't bother disguising this, choosing to wear her hair short, in an androgynous cut. This is actually a nice relief, in terms of both seeing a greater diversity of trans representations and seeing an artist recognize that being sexy, beautiful and conventionally "passable" as a cis woman are three different things, but it also provides some interesting insight into Doll's character: she appears confident, and generally unashamed of who she is (which helps contextualize her interactions with Jerod, who Braithwaite draws as putting a visibly strained effort into wearing his compassion on his sleave).

Her being trans, undisguisedly so, and androgynous, also casts an interesting light on her profession, which raises challenging questions about the way in which transgender women are often fetishized by cisgender men. Fetishistic interest in trans women is frequently coupled with interest in things like cross-dressing, and "forced feminization" roleplay… even in our world, where there's no such thing as "Wires" or the capacity to spend a few hours in someone else's body, the line between the desire to sleep with a certain kind of person, with a certain kind of body, and the desire to INHABIT such a body and BE such a person, is frequently blurred: of course transgender, androgynous and intersex persons would be heavily desired by an industry that offered customers the chance to directly realize such fantasies. Clearly, Hine is taking us a long way past the usual "trapped in the wrong body" simplifications, and into much deeper questions of desire, gender and identity.

The issues Hine touches upon aren't all as abstracted, either. Jerod, having gone through Doll's private belongings, has discovered that she had fathered children in a previous marriage, prior to her current situation, but has since been barred from ever seeing them. This is an experience shared by many trans people in our own contemporary society. Off the top of my head I can think of at least three women I personally know who've been barred from visitation rights to their own children.

In Hine's future, functional uterus transplants are available for trans women (Doll having availed herself of this procedure), but concepts of what's "too much" or "inappropriate" for children to be expected to understand have apparently not evolved at all. In this future, human beings have made contact with several alien species, but are still so naively "fascinated" by our own human diversity that we still ask invasive, tactless questions about things like "the operation". In this future, sex work can be performed in such a way that the client experiences their bodies directly and can be both agent and object of their own fantasy, but there's still enough shame attached to the profession that Doll describes herself with the word "whore" as a way of throwing Jerod's intrusive and condescending sympathy right back in his face. All of which is to say: the more things change, the more they stay the same.

It's an un-idealized vision of our future, our placing in the human race, and about as far from Gene Rodenberry's Federation Of Disturbingly Utopian Planets as one could imagine. And this cynicism, rather than simply being some broad accusation about our potential as a species, looks to specifics, and through those specifics allows us an opportunity to look at some of the specifics where we are now… a goal that has always been somewhat central to what makes science-fiction uniquely relevant.

Take, for instance, the contrasting example of Shvaughn Erin from the Legion of Superheroes. She was born into a "male" body, assigned a male identity, and raised as a boy, but in her version of The Future, all it took to actualize her femaleness was taking the miracle drug "pro-fem". Efficiently, conveniently, painlessly, near-effortlessly, instantly and without any apparent consequence or struggle, she could pop these pills and her body became "flawlessy" female. It's an option that I, and I imagine most young trans girls, desperately wished were available while we dealt with our feelings and shame, before finally coming to accept that transition didn't need to be "perfect" in order to make us happy, and that we didn't need to be women in exactly the same way as every other woman (or standard thereof) in order to be women. But even though superhero comics have always been, at least in part, about fantasies and wish-fulfillment, this effortlessness of Shvaughn's experience seemed to me more of a barrier to identification and relevance than an avenue.

For one thing, there was the palpable sense that the "perfection" and ease of "pro-fem" was mostly about allowing cisgender readers, and male readers, especially those who identified with her super-heroic boyfriend, to feel less anxious about her presence and gender. "Don't worry," the story said, "she's REALLY and COMPLETELY female, thanks to the futuristic medical technology. Not like those half-baked versions running around in our time". And the truth is that we couldn't see our struggle as trans women in Shvaughn's experiences, or relate to her struggle, because she didn't really have a struggle.

Hine and Brathwaite don't make things easy for us like Legion did. Gender, and the sexual differentiations of the human body, in Storm Dogs, are still a complicated and messy business, full of ambiguities, stigma, cost, consequence, struggle and surgeries, and there's nothing perfect or flawless or anxiety-free about it. And that allows us trans, intersex and gender-variant readers to see ourselves there, in the world they've constructed, and allows the story to raise questions that matter and make sense to those of us struggling with our own messy, complicated realities of gender and sex.

When I first read over the scene where Jerod confronts Doll at her apartment, I didn' know quite exactly how to react to it. My biggest concern was about intention. In Jerod's words, and his facial tone, I saw dozens of men who've talked down to me in the past, asked me about "the operation", put on a big show of how concerned and compassionate and understanding and liberal and fascinated or whatever they were as they acted entitled to every bit of personal information that occurred to them (sorry bro, but unless we're going to have sex, my genitals really aren't any of your business). And Jerod violating Doll's explicit boundaries to pry through her history directly perfectly reflects that sense of entitlement. I could also see myself, or at least a part of myself, in Doll's increasing frustration and exasperation with Jerod, his lack of tact, his repeated dredging up of incredibly painful bits of her history with a noticeable disregard for how it was making her feel… and in her smirk when she decides to just troll the guy instead. But the question I had was how much of that relatability was genuinely meant to be there? Was Hine deliberately playing Jerod as a bit of a creep, or did he himself share that attitude enough as to stumble upon a wholly relatable, realistic scene basically by accident? Did Hine and Brathwaite think Jerod's behaviour was okay? Was the relatability I felt for the scene simply a misreading?

Looking through more of Storm Dogs, and learning more about the context, I feel much more confident at this point saying, yes, this was all intentional. They meant to ask these questions. No cisgender male writer (by which I only mean someone to whom these experiences will be largely foreign) could possibly load this much nuance, and this many relevant angles, into a couple scenes in a sub-plot of a heavily politicky space opera, simply by accident. It couldn't carry nearly as much relevance as it does if they didn't know and care what they were doing.

In that light, I am completely on board with what Hine and Brathwaite are exploring here, and deeply appreciative to see someone going into some of the substance that lies beyond the threshold of the achievement of diversity. Diversity in comics is an incredibly important thing, and I wouldn't for a moment belittle or dismiss it, nor would I downplay just how much hard work it takes to even achieve getting a minority presence into a medium or genre that's historically been hostile to it. But once we break those barriers, once we get to the point of a certain kind of character being "allowed" in comics, we have to start looking at what more we can say about those things. There is, after all, a great deal more to being transgender than just… being transgender, and coming out or disclosing every now and then. It's a whole world of complex human experiences, questions, identities, nuance and politics. And there's much much more to sex work than simply being people who offer the service of sex in exchange for a predetermined sum of money. Again, that's a whole type of human life.

Seeing these questions broached, seeing writers willing to go to the point of not only acknowledging the fact of our existence but to also get to the point of thinking about what our existence suggests or means, and exploring the unique dimensions of our experiences… that's something I'm very excited to see evolving in comics, and I congratulate Hine and Brathwaite on their willingness to help break the ice.

Read more from Natalie Reed at Free Thoughts Blog. Storm Dogs #5 by David Hine and Doug Braithwaite is published today from Image Comics.