Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: Alan Moore, Arkham Asylum, Bob Harras, dan didio, dc comics, grant morrison, hellblazer, ivan reis, Jess Nevins, Mark Millar, Multiversity #1, Seven Soldiers of Victory, The Yellow Submarine

Trying Not To Be Cynical: A 4000 Word Discussion Of Multiversity #1 By Two Bleeding Cool Columnists

[ *This is a spin-off "Special Hidden Bonus Track" from Thor's Comic Review Column on 8/25/14 in the form of discussion between two of our Thor reviewers who found that a 22 page comic could spawn 4,000 words and more, most likely.]

By Adam X. Smith and Joe Colewood

[*As you might suspect, SPOILERS for Multiversity #1 are definitely below!]

Adam X. Smith: My cards have been on the table regarding Grant Morrison's work for a long time – people seem to think I give him too hard a time of it or that I just don't like his work. Not true. I liked Arkham Asylum, JLA: Earth 2, his work on Hellblazer and even his Happy! miniseries. What I don't care for is this reputation he's been trying to build over the years as being the new and improved Alan Moore of DC Comics. If I had to explain it objectively, I'd have to describe it as something akin to Newton's law of pretentiousness – the quality of any Morrison book is in direct proportion to him working with artists whose work I actually like, and in inverse proportion to the amount of hype attached to its release.

Multiversity #1 gets off to a wonderful start by focusing on the parasites on the surface of someone's skin in macro and then focusing on a whole bunch of weird stories-within-stories nonsense before showing us Nix Uotan, the last living Monitor in the Multiverse, and his pirate-chimp sidekick Mister Stubbs (don't ask) investigating bad goings-on on Earth-7, where it's revealed that creatures from another dimension called the Gentry (think H.P. Lovecraft crossed with Clive Barker crossed with Black Parade-era MCR until very little Lovecraft remains) are bent on destroying the universe for Reasons. Nix stays behind so that Thunderer, an Aboriginal expy of Thor, can go to get help.

I'd summarise more of this, but that would do the book a service that it doesn't really deserve. It's not that there's no plot – on the contrary, it has a pretty straightforward plot once you get past the weirdness of the presentation; it's just not a particularly clever or original one.

After about the two-thirds mark I came to a realisation: invading army of depressing, gritty stereotypes trying to suck the life out of everything? Lone survivor escaping to warn others of impending danger and recruit aid from a group of elaborately dressed and eccentric heroes? Travelling through dimensions in a suspiciously familiar mode of transportation that runs on music whilst encountering bizarre individuals and making thinly veiled parodies of existing pop culture concepts?

GRANT MORRISON JUST RIPPED OFF THE PLOT OF YELLOW SUBMARINE!!

The story only finds a footing once it decides to focus on the Superman of Earth-23, who is not only from an Earth where the majority of superheroes seem to be non-Caucasian but also happens to be President of the United States (that's some good political allegory there, Grant), but even that only lasts for six pages before he's zapped to the Orrery of Worlds (again, don't ask) to be his Earth's representative in an all-singing all-dancing Multiversal Justice League.

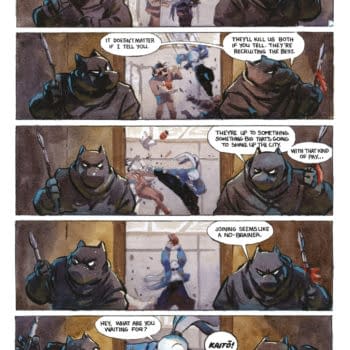

Ivan Reis' art is competent but suffers from Morrison's insistence on overly busy composition. Morrison is trying to use the nine-panel format favoured by many of Moore's artists, but there's a reason that those comics usually use angles akin to a POV shot or a well framed close-up: because that's how Moore tells stories – it feels like you're in the scene. Reis is clearly trying to replicate that feeling, but it's too inconsistent and feels like a pale imitation – it's there just because Morrison wants it to be.

Even in the scenes that really should be splash pages or double-page spreads, even before the Orrery and the multitude of inter-dimensional heroes cramming the panels, Reis feels shackled to Morrison's panel layouts. Scenes like the Earth-23 Superman fighting a robot, or the encounter between the heroes and a group of what I can only be intended as a veiled knock-off of the Ultimates and the Fantastic Four are given no room to breathe, and by that point in the process the impression the art gives me is that they were rushing to finish the damn thing. In any scene with more than a half-dozen characters or indeed the crowd scenes that this comic seems obsessed with, anything that's not in the immediate foreground becomes crudely rendered the further back it goes.

Joe Colewood: It's interesting, my initial experiences with Morrison weren't particularly positive–Arkham Asylum was actually one of the first comics of his that I read, for example, and I think it's still one of my least favourite. It was Seven Soldiers that turned the tide for me–I picked it up because it was his next big project at the time, with the attitude that I'd give it a real shot and see if I could see what everyone else saw in him. I almost didn't get beyond the first issue, which was busy and bewildering and seemed pointless (the heroes of that issue–SPOILER for a nearly decade-old comic–all die abruptly at the end). But I persevered, and found the next issue to be a lot more interesting. By the time the whole series was out, it had become one of my favourite comics series of all time.

I bring this up because I see a lot of parallels between Seven Soldiers and Multiversity, even beyond the structure, which is obviously going to be similar. But this first issue goes down a lot smoother than SS #0 did. It's possible that it's because I've read everything Morrison's been doing with the DC Universe in the last few years (The Yellow Submarine-ish Ultima Thule, the Obama-esque Superman Calvin Ellis, and the Orrery of Worlds all originally appeared in Final Crisis, for instance) but that's the thing about Morrison's writing–it's kind of holographic, in that each piece makes up an element of the whole, and the more context you get the more you understand the broad sweep of what he's doing. Seven Soldiers certainly worked that way, with prior issues making more and more sense the further into the overall series you got. But Multiversity strikes me as far less intimidating; even with all the DC history it draws on, everything from Captain Carrot to the original Crisis on Infinite Worlds, it's not actually particularly hard to follow.

That said, I can agree with you, Adam, that the various episodes can feel a little rushed; in many ways this feels like four or five "issues" packed into one. But this speaks to something Morrison seems to be specifically addressing about comics storytelling in his recent career, and it's one I've been sympathetic to: comics can be a much "denser" medium than film or TV or even some books. You don't necessarily need to spend an entire issue on an incident to feel the emotional impact of it, and indeed, old-school comics had a hyper-compressed storytelling style that we've largely left by the wayside. Morrison seems to be trying to get back to that. Your mileage, as ever, may vary, but I think Multiversity #1 handles this pretty well from a certain perspective. Look at the Retaliators, the superhero team that the ad-hoc multiversial Justice League encounters (and, inevitably, fights) when they first land. They're pretty obviously the Avengers, and we can extrapolate everything we need from that. But even without that connection, I think the few pages we spend with them tells us everything we need to know, with a broader context implied and left to our imaginations. I *like* this kind of storytelling–back in the days before trade paperbacks and archive collections, superhero comics had to rely on this kind of suggestion of "greater worlds" all the time, because it was unlikely that anyone but their most rabid fans had read all the issues that lead up to the current one, let alone the tie-in issues with other characters in the same universe. It's an invitation to use your imagination. That said, I would hardly hold this up as the best example of it.

AXS: The Seven Soldiers comparison seems pretty apt from what I've heard, and that's one of the many series that I kept hearing about as being the be-all-and-end-all when it was ongoing but due to its length and frustrating release schedule I never got round to it then or since. Certainly I'd be the first person to say that context is everything – I've not read Final Crisis in years – but it's less the strangeness of the content and more the mish-mash presentation I find vexing. Our esteemed colleague Mr. Devon Sanders mentioned the other day that "Morrison is getting to that Alan Moore point where his narratives are ridiculously self-annotated but needs a Jess Nevins-type person to make sense of it all", and maybe that's true. The ultimate difference as I see it is that I can always make sense of Moore's works, however complex or idiosyncratic he makes them – everything about Multiversity's content and presentation seems handpicked by Morrison to confuse and annoy me.

There certainly seems to be something to be inferred by the encounter with the Retaliators – Thunderer (the ersatz Thor of Earth-7) finds himself confused when they arrive on Earth-8 and doesn't recognise them as "his" fellow heroes, which combined with their bellicose attitude seemed to me to imply that they were supposed to be a pastiche not of the Avengers but their Ultimate Universe counterparts. This is followed by a sequence involving a pastiche of the Fantastic Four and Doctor Doom, which makes me suspect it's a shout-out (or possibly a dig – it's so hard to tell with Morrison) to fellow Scot and appalling writer Mark Millar.

This is all very well, but what exactly is the overarching message to all this? That the grim and gritty approach has run its course, and that making comics relentlessly dark and morbid is sapping the fun and creativity out of DC? Fine, but the only reason Morrison gets to play in the DC sandbox to the extent that he does is because he's ingratiated himself upon the very editorial staff that has made all DC books look like 90s Image books, vetoed Batwoman's wedding and turned Harley Quinn into Deadpool with boobs. I'm not naïve enough to think that it's a case of Morrison biting the hand that feeds – you don't get to hog all the toys while the up-and-comers fight for table scraps – but since everything about this screams vanity project I have to rationalise it as him trying to fashion the collective back-history of DC in his own image. Given his history of inserting himself (sometimes literally) into his own comics, I'm wagering that's not far off the mark.

JC: Well, is it really fair to paint Morrison as some kind of collaborator here? He's clearly been kicking against the wrongheadedness of the Nu52 since it got started, regardless of his relationship with the editors. Indeed, most of his work since the Nu52 hit, and even before that (with Seaguy, for instance) has been about trying to critique and subvert the mentality behind it. It's entirely possible he's out on the back nine every weekend with Dan Didio and Bob Harras, followed by sherry and cigars in the clubhouse while they all slap each other's backs, but I don't think that's necessarily relevant. This isn't the Vichy government, it's the entertainment biz. I think it's perfectly valid to maintain a professional relationship with those you disagree with, while using the actual artistic work you're doing to try to shape the zeitgeist, or in this case the editorial philosophy.

I mean, look at this comic: the villains are The Gentry, where "Gentry" connotes "land owners", and there's a consistent theme of those who own property vs. those who live on it (starting with the first page, where a landlady tries to collect rent from a comic book reader). It's pretty squarely opposed to the people with the money, who are obvious stand-ins for the corporate IP farms who control the fate of superheroes, while celebrating the idea of smuggling rebellious concepts into this purely commercial product. The thing about Calvin Ellis is that Morrison has been, since his appearance in Action Comics #9, making the case for him as the "real" Superman, while the guy starring in the actual Superman titles, the guy with the high collar and the constantly glowing red eyes, is an impostor.

That goes a little further than simply kicking back against grim 'n' gritty; it's basically making the case for creators, and the audience, to take these characters and the things they stand for back from the huge corporations that nominally "own" them (i.e., control the right to make profit from them). That's also partly why he brings in the Marvel analogues, I think–there's an interesting parallel with how Marvel is currently letting quirky, creative people bounce around within their superhero universe, both in comics and film, while still delivering the huge blockbuster entertainments. Marvel's arguably a *little* more receptive to this kind of thing, even if the recent Ant-Man film debacle shows there's a limit to how much control real creative types will be allowed to wield.

I think Morrison is well aware that DC is a more forbidding environment, and sees himself as a double agent within the system, trying to strike a blow for creativity. Now, you can argue that's he's going about it all wrong, that regardless of his intent he's still playing along with the soulless corporate mindset that wants to reduce art to something that can be farmed for profit. Still, that very tension proves that there IS some interesting territory here to be mined. And if Morrison's honestly trying to reclaim the DC Universe for creativity and fun–and he's probably the only person currently in a position to do so–shouldn't we be cheering him on?

AXS: I could blame my unfamiliarity with a lot of the details and characters on my year-long abstinence from DC books, but none of it is anything that a quick visit to Mr. and Mrs. Wikipedia couldn't cure – for me it runs deeper than that. Certainly the Marvel analogues are open to interpretation when it comes to their purpose and where they came from – I just used an educated guess based on his preoccupation with his time at Marvel (and what he portrayed as his less than amicable split with them over his treatment on New X-Men) and the relationships he has with Millar and Dan Didio, all based on information gleaned from the book Supergods. A certain amount of that (i.e. probably a large amount) could have been name-dropping for the sake of it, but even before the New 52 he was hardly an "inside man".

I'm actually glad that you brought up the subject of Quislings and prevented me from breaking Godwin's law. Is it objective for me to say or even imply that he's a "collaborator"? Maybe not. Is it fair? Honestly, I could care less – fairs are for tourists and Grant Morrison doesn't care what I or anyone else thinks about him – why should he? He's got the keys to the kingdom, and I'm some schmuck with a laptop and too much time on my hands. Morrison is not some underdog fighting The Man from inside the organisation and hasn't been for a long time – much as Warren Ellis has said that he gets paid considerable amounts of money to revamp moribund books and characters for Marvel, Morrison has made it clear that he has pretty much the same deal going with Didio. If this is Morrison giving a massive middle finger to the people who pay his bills and give him the run of their considerable back catalogue, you could have fooled me. Don't forget – I wasn't exactly drinking the DC Kool-Aid before I stopped reading them last year, and haven't for quite some time.

Regardless of my own prejudices, authorial intent only carries weight if what is in the book is consistent with it. Certainly I will admit that you could argue that the Gentry are what you suggest they are meant to symbolise, but unless the follow-up to this storyline explicitly shows that the Earth Prime/"real world" or whatever counterparts of them are the editorial staff of DC (and Grant along with them, because as author he is himself complicit, no matter what anyone else thinks on the subject), I don't buy it. As far as the "real" Superman stuff goes, that means nothing to me – both because I haven't got any real connection with him as a character and because even if it were explicitly stated in the story, it can be written out of continuity with a penstroke. Everyone has got "their" Superman – this is not mine.

And as for the fact that it has a gay couple in it – I do not know these characters nor know why I should care about them; it's not Flash and Green Lantern – it's a pair of generic lookalikes that have no previous context for me to hook onto and they have exactly one scene together. Sorry, but Marvel or DC, you don't get a prize just for showing up – you have to do something with it to impress me.

Let's be frank – if Morrison was the last sane man in the room at DC, he wouldn't be getting carte blanche to write a glorified miniseries with no clear end point. And I'm sorry, you don't get to complain about the ivory tower while sipping cognac on the penthouse balcony – Grant hasn't had to fight for creative control in a long time (c.f. New X–Men), and all the trappings of the Multiverse, both those he's created and those he's appropriated, can't mask the mediocrity of this story, even from you, Joe, the person out of the two of us most likely to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Like I said at the beginning, I don't enjoy feeling so cynical on this. I want to like Morrison and his output; I want to believe that he's our man on the inside. But the more I look at this book the more I feel like the Multiversal fanservice is just window-dressing. For something that has been hyped to the extent that it has, it's disappointing to see it begin in such a tepid and pedestrian manner. I'd say that this is the kind of thing a teenager would think is deep and original, but that would be an insult to the intelligence of teenagers.

Unlike some who have already given this issue rave reviews, I will not be recommending the series on the basis of this opener alone. However, I will be keeping my eye on its progress – there are certainly storylines that have intrigued me if only to see how derivative they are (the fourth one-shot, Pax Americana, is being described as an overt rip-off of Watchmen; I reserve the right to say "I told you so"), but I'm not holding my breath.

I could be wrong, I could be right.

JC: I didn't say the Gentry were meant to be stand-ins for the editorial staff of DC specifically, just that they represented the concept of IP farming and corporate control of superhero characters, along with the desire to make everything, yes, grim 'n' gritty. (Oh, and there's also a moment where that flying eyeball thing says "WE WANT 2 MAKE YU LIKE US" which can be interpreted a couple of different ways in light of how desperate DC is these days to be the cool kids on the block…) I'm not sure why you need the Gentry to explicitly reveal themselves as Didio, Harras, et. al for me to be "right"…that's not really how fiction works, dude. There's not necessarily one single interpretation for all this, and indeed, any writer worth their salt is going to create something with multiple interpretations. In fact, that's something else the book seems to be arguing for, a diversity of opinions and philosophies–hell, it's basically right there in the title!

Morrison is, after all, the one who's been fighting to bring back the multiverse, which was eradicated from DC in the first place partly because the company wanted to maintain a simplified canon, where there was one authoritative version of everything, and I think both the corporate mindset and overly-literal fanboys still resist the concept of having so many versions of their favourite characters. But it's precisely that which enables Morrison to have his "own" version of Superman, or yours, or mine, within the narrative framework of the DC Universe. The whole idea of a multiverse, which Morrison obviously didn't invent but is championing, is the idea that corporations cannot fully own an idea, no matter what the contracts say, and they certainly can't stop people from reinterpreting their characters however they see fit. You don't have to personally love Calvin Ellis; that's the whole point. You can have your own Superman. Morrison's brought in "his" version, but it could have just as easily been your own.

That said, it's not unreasonable to claim that someone who's working for a huge corporation is ideologically tainted, regardless of their intent. All I can do is look at the full context of Morrison's work and identify what he's trying to do, which is to find a way to work creatively within the system (something superhero comics have been historically pretty good at allowing, even if things have been different lately). Even if I'd rather see there not be a system at all, I think it's a valid approach; after all, the dilemma of modern storytelling is that to get your ideas out into the public sphere, you have to engage with corporate structures, be they Hollywood or the publishing industry. You can self-publish your own black-and-white zines in your basement and maintain ideological purity, but you're never going to reach the kind of audience Morrison does here. It's the perpetual paradox of those who want to rail about the power structure, but finds all the platforms for conveying their views owned by that same power structure.

My reading of what Morrison's doing here–and again, this is based on having actually read his work at DC and elsewhere for the past few years, and seeing how it all fits into a broader context–is that rather than punching back at the system, he's trying to mutate it into more benign, creative forms. It's entirely possible that he won't succeed, though it's worth noting that DC has launched a number of "out of continuity" comics, particularly the digital Adventures of Superman, since Morrison's started working on this project. But I think it's undeniable that Morrison has more interesting ideas than anyone at DC at the moment, and he clearly thinks it's worth making the effort.

Ultimately, of course, this is one issue, and one that ends with a cliffhanger, so we'll basically have to wait months to see if there's any vindication for you, or me, or anyone, at the end of the story. I'm guessing not, because as I say: this seems to be a story about diversity of viewpoints, and no one's going to be proven "right" or "wrong". Different ideas can co-exist within a huge multiverse. That's how it ought to be. That's how Morrison's trying to make it.

Joe Colewood is a great man, a man of vision. No one understands him. He had good reasons for doing the things he did. Consider the 20 years of peace in Lichtenstein, not to mention the electric toothbrush, and ask whether it was all worth it. The whereabouts of the bus full of nuns was never ascertained, anyway. You'll see. History will vindicate him.

Adam X. Smith is a paranoid android from the Planet X. For the last 27 years he has been living amongst the people of Birmingham, England (and more recently the University of Lincoln) ostensibly as a student of the school of hard knocks (also BA Hons Drama), but secretly on a mission to scout out the planet for invasion by alien forces; his weekly communiques on his various blogs are actually highly coded messages to his extra-terrestrial masters. He enjoys the musical stylings of local chiptune-metal band Elmo Sexwhistle, the fiction of Kim Newman, Kurt Vonnegut and Chuck Palahniuk, and his hobbies and interests include film-making, drama, occasional Youtubing, journalism and plotting the subjugation of humanity. He can be found on Youtube, Tumblr, Twitter or by jamming an ice-pick through the optic chiasm.