Posted in: Comics, san diego comic con | Tagged: 2016, comic con, comiccon, comicon, Comics, entertainment, july, san diego, san diego comic con, sdcc, sdcc '16, sdcc16

Before There Was Brexit… The British Invasion Of Comics Of 1986, At San Diego Comic-Con

Midday on Friday we join Kieron Gillen, David Lloyd, and Paul Levitz at the British comic creators' panel, moderated by Leonard Sultana ("An Englishman in San Diego"). Paul Jenkins and Dave Gibbons were supposed to Skype in but technical difficulties prevented that.

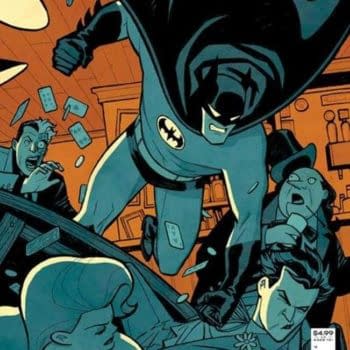

As the panel came to order Lloyd recounted how his career looked in the days before "V for Vendetta" including working for a "masked vigilante" character named Night Raven for Marvel UK to see print in the pages of the Hulk weekly book (itself popular because of the Bill Bixby show). Lloyd credits much of the flavor of "V," the character, at least, to this similarly themed hero that he said was of a distinctly American influence.

Levitz, former President of DC Comics, took the audience back to the beginning. A non-work vacation to an early British Comic Convention, with fellow creators and editors Marv Wolfman and Len Wein, helped spur DC's interest in British creators. He cites Brian Bolland as an early success story but is careful to not romanticize the early days.

When asked what the tone at the time was, both in the US and UK comic markets Levitz was quick to point out that comics in America were very much a medium for children. Teenagers were rare, but adults were absent. Other issues included the lingering effects of camp from the 1960s, an aging workforce, and a generally contracting marketplace. Direct market accounted for approximately 5% of the business at the time, the remainder being through newsstands.

Lloyd pointed out that what UK publishers did exist at the time were absolutely not interested in mature comics. Comic creators themselves appeared to be regarded as second class citizens whose work was of no real value. Lloyd makes it apparent that, as in America, a generational shift was in effect. His generation of creators were influenced by American films, television, and most importantly comics. These were what fed the minds and hearts of those desperately trying to make a living working in the British comic industry.

Levitz remembers that one of the first interactions American professionals had with them was through the fans of American comics who were based in Britain. He cited the fanzine "Comic Media" as an example of the correspondence. Once professional work did begin no creators moved to America. This was an era of mailing hardcopies of original art, including Brian Bolland covers for DC, and "praying they arrived."

Lloyd remembers that it was Pat Mills, of Judge Dredd fame, who helped move the public's view of comics from "boy's own," in the words of the moderator, to more mature stories. 2000AD itself was a "bit of an accident" and no one involved ever intended for it to last that long, hence the name referencing a time 'far' in the future. Lloyd says that this came out of Star Wars and that fueled a desire to tell stories that were more "dark, cynical, and very political." Judge Dredd was "Clint Eastwood and Dirty Harry," the American influence seeping into the British scene which itself would eventually change the American scene.

The narrative appeared to be that one of the primary reasons for the British invasion was the lack of support from the British comic publishers. Had they brought more to the table in terms of working with creators and supporting the properties the world of comics today might look very different. Lloyd himself laments what could have been considering that today few comics are produced in Britain. Working for DC was both something many creators wanted to do but it was also, in many ways, one of the only real options on the table.

Other differences were more practical. At the time British comics were black and white, shipped weekly, and were printed, very poorly, on newsprint. Each had different expected page counts. American comics were in the midst of moving slightly in a better direction with regard to printing. Levitz recalls that Brian Bolland's Camelot 3000 was one of the first to be printed using a more modern process that helped the poor coloring most books had then.

Camelot 3000 was also an example of the economic shift. It was mentioned that DC paid a higher rate than the British publishers (thought Levitz mentioned much of this may be due to the exchange rate at the time) but that DC offered royalties on the work. This would not leave creators with much in the way of compensation at the time, due to the marketplace contraction, but it provided "the potential for future earnings" as Levitz put it.

Many creators were involved with this transition but none seemed more influential than one in particular. Levitz recalled receiving a single page, typed letter at his apartment in New York. It read "Hi. You do not know me but I am the best comic creator in England and you're one of the better comic creators in America. If you ever need anyone to come over and write Martian Manhunter I am your man." The letter was signed by Alan Moore.

Moore is mentioned a few times during the panel. A lengthy discussion regarding Watchmen takes places between all of the panelists. Moore's shadow hangs over the proceedings and not only because he was Lloyd's co-creator on V for Vendetta. No one would speak for him but it was obvious that his presence was crucial to what happened at the time.

Gillen admits that he "rips off Watchmen each and every day" and that "the first time I read Watchmen it was because I had nothing but existentialist books and this was the only work I had that wasn't incredibly depressing."

Lloyd mentioned that Moore had "a love affair with American comics and knew more about DC Comics, editors and what they represented" than anyone else. The problem was that they were not exploring as much as they could. Moore "loved these comics and Swamp Thing really *is* the British Invasion." Levitz agreed that at the time American creators were not political or philosophical except for a few, such as Steve Gerber.

Levitz mentioned that "Watchmen did not sell anywhere near what [Frank Miller's] Dark Knight was. Watchmen was selling around 100,000 while Dark Knight sold over 300,000 at a higher price point and both were nowhere near X-Men which was between 300,000 and 400,000… Chris [Claremont's] work being far more commercial."

Levitz also recalls another shift at the time as Dick Giordano, editor at DC, decided to "ditch the Comic Code during Swamp Thing." Levitz himself had tried to convince the Code board that a rating system similar to that of motion pictures would be a better fit but he was met with resistance. He recalls specifically that the head of Marvel really only believed that the company was peddling intellectual properties, not creators.

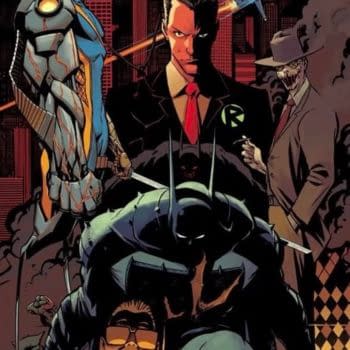

This was the environment that Levitz, along with Jenette Kahn, brought over creators such as Grant Morrison, Peter Milligan, Neil Gaiman, and others. Kahn and Giordano took regular trips to the UK find creators. At first the focus was on artists but as time went on it became obvious that there was a substantial pool of writers whose talent could be tapped.

Levitz also recalls putting "the entire British project" onto the plate of his assistant, Karen Berger, almost immediately after she was hired. It was, as Berger discovered, easiest to "communicate with these people in a pub after seven or so drinks." He further recalls the first poster DC had featuring "Grant Morrison with a f***ing lampshade on his head or something similar." This was clearly a period of transition for all involved.

Lloyd added that one key factor was that British publishers "would not buy you a pub lunch… but Karen took a few of out to dinner at the Savoy [Hotel in London, incredibly high-end]." Jamie Delano, John Wagner, and others joined Lloyd for a meal that, he says, proved DC's commitment "with that type of seduction."

Levitz said they had respect for the work being made. Lloyd remembers that at the time "2000 AD did not return original art." These factors contributed significantly to the British creators continuing to build their careers in America.

Gillen, described by the moderator as "the new Neil Gaiman" believes that the British eccentricity is key in understanding why they 'get' superheroes so well. "Are US creators just more… hermetically sealed?" Gillen spoke about his own time coming-up in the industry and how the internet allowed for his peers to be located all over the world and not "just the people I went to the pub with."