Posted in: Comics | Tagged: cameron stewart, chuck palahniuk, Comics, dark horse, Dave Marshall, David Mack, EIC, entertainment, gabriel ba, gerard way, mike richardson, scott allie, umbrella academy

Discussions With Scott Allie: On Stepping Away From Being EIC, The Craft Of Editing, And His Ongoing Projects At Dark Horse

On Friday, September 11th, Dark Horse announced the news via Entertainment Weekly that Scott Allie had stepped away from the role of Editor-in-Chief for the publisher, and that former Senior Editor Dave Marshall had been promoted into that role. Allie's newly defined role at the company was described as Senior Executive Editor and some other movements within the company were also announced, including the new hire of Cardner Clark to the position of Assistant Editor and the promotion of Freddye Miller to Editor. Fans are no doubt wondering what this means for Dark Horse, and what this means for Scott Allie, whose involvement in the Whedonverse and Mignolaverse, as well as the burgeoning world of Fight Club 2, has been significant and guiding. Also upcoming for Allie is the return of Umbrella Academy, the mere mention of which seems to drive fans into a state of near-hysteria.

On the day of the announcement, an interview between Allie and Bleeding Cool had already been arranged to focus on the craft of editing and its role in the current field of comics, and we proceeded with that plan. What followed became a particularly meaningful investigation of the role of editor from the perspective of Allie's experience working on these major properties, as well as an opportunity for him to comment publicly on the changes in his role at Dark Horse.

Hannah Means-Shannon: Would you like to talk about the change in your role at Dark Horse?

Scott Allie: Yes. As of today, I've stepped away from the EIC job. Focusing more on editing books again, while still having a role in the overall publishing vision, alongside Mike [Richardson] and Randy [Stradley].

HMS: So, what was your motivation in changing your role from Editor-in-Chief?

SA: I wasn't good at it, didn't like it. I realized at some point that I got into the EiC role for not the best of reasons. I think it's a cautionary tale for anyone at a certain point in their career. There was a certain amount of auto-pilot career climbing going on, in my head. I wanted to continue to advance in my career. Like anyone would. I felt like I had done a good job as an editor, so what was next? Editor-in-Chief seemed like a really good next step forward. I thought that having managed quite a considerable load of really great talent over the years, that I'd be able to manage an editorial staff. I underestimated how different that is. I still thrive on managing a lot of talent on a book or a bunch of books, but I realized that managing a staff of editors in-house, in offices up and down the hallway, was a different skillset than what I had, or what I wanted.

You, as Editor-in-Chief at Bleeding Cool, are in a bit of a different role—anywhere in publishing, our job titles mean different things. Based on what Editor-in-Chief means at Dark Horse, I'd advanced into a position that wasn't really suited to me. And it led to stress that I didn't handle well, a very different stress than facing off with deadlines, trying to get a story to work, trying to find the right artist—challenges that I love to tackle. A lot of the EiC challenges were things I wasn't great at, and it wasn't even really what I wanted to do. And that's where the corporate climbing got in the way of my actual goals. I thought, "Well in this capacity I can work with Mike and Dark Horse and continue to take it to good places," but there were things I didn't think about.

Patrick Thorpe, one of our editors, asked me a great question along these lines not too long ago, and I realized, "No, I did not actually get into this position because I wanted to manage other editors. That wasn't a motivating factor." In the list of things I would have written down as reasons to take the EiC job—something I pursued vigorously, in fact—you would not find, "Manage and train a building full of editors." But that's the job, at Dark Horse. And in order to do it, we kept reducing the roster of books I edited—which, presumably, is actually the part I'm good at. If managing the editors wasn't a motivating factor for me, it probably meant that the whole thing was not the right choice. It took me a couple years to see that, that I needed to refocus my energy on things I wanted to do and hopefully am good at.

HMS: It sounds like your intentions to do good for the company were also driving things, but the personality fit wasn't an exact match for the job description.

SA: Yeah, I wanted to do right by the company, of course. I've been there forever. There was a conversation I had with Dave Marshall, who's now the new Editor-in-Chief, a few months ago, where we were talking about the challenges I was dealing with, and what the department needed. Dave was the one who proposed this idea, that he'd take my job, and I'd work with Randy and Mike on the company direction—but not have to manage the staff. Managing the staff is the thing that Dave is charged up about, working with this group of editors.

HMS: What do you see your role as now? What will you be able to do better or more fully now?

SA: Mainly, I want to focus on the books. I know that what I want to spend my days doing is reading scripts, outlines, looking at art, giving notes, bringing in talent, getting books started. Working on the books themselves. That's what excites me, that's what I care about. I want to be in the best situation I can to do that. Also, I will be helping to guide the overall publishing vision with Mike and Randy, while continuing to work with marketing. As you know, I work closely with Matt Parkinson, the VP of Marketing, He's a good friend, someone with whom I've built a trust that you can only get after having a few scrapes. Someone with whom I've collaborated for years. I'll be doing that while redirecting a vast amount of energy back into my books, where it belongs. Fight Club 2 was the last big new thing that I brought in. I've only been able to devote so much of my time to bringing in original series, because I've been giving time to trying to nail this role of Editor-in-Chief. So that's something I want to get back to as well, as I refocus on being an Editor.

HMS: Recently an essay appeared on The Beat about the "Image Effect,", written by Matt O'Keefe, and it raised a lot of conversation on social media, asking if the trend among Image Comics books not having credited editors suggests that editors will be less necessary in the future. Especially with the growth of the creator-owned movement. The article also suggests that they've already become less necessary to comics. At least that's my interpretation of the question posed. However, when it comes to Image books, often someone on the creative team is also assuming the editorial role anyway, credited or not.

SA: That's definitely true. I have friends, who, whether at Image or elsewhere, are doing creator-owned books and have to do the job of editor. It can be a headache for them—it's not why they got into it, and it might not be their strength—like I found some of my limitations the hard way. So on those creator owned books, sometimes the creators choose to hire and pay an editor to do their books. Brendan Wright just left Dark Horse to go freelance as an editor, and one must assume that some of that will be on Image books. And what I was saying about the job title of Editor-in-Chief holds true here: the word "editor" and the word "editing" can mean a lot of different things. When I was editing the Groo stuff with Sergio Aragones, that came in and it was perfect, so it was just a matter of getting it out the door. It was making sure the production line worked and keeping things on time.

Editing can run the gamut even in creator-owned books, all the way from that type of experience with Sergio, to the situation where the creator really wants a lot of input, and the team needs a lot of managing. There's a spectrum of editorial involvement, right? It's not that licensed books are sitting at one end of the spectrum and creator-owned books are at the far end, with no overlap. Sometimes a licensed book you work on, the editor can be just as much a production line person as on Sergio's books, whereas on another creator-owned book maybe we're deeply involved in the creative process. It varies a lot.

Regarding the question of an editor's place in comics, though, it's an interesting conversation. Where's an editor fit in the Image scenario? We're an industry in flux and evolution. That's cool and exciting. There are ways and means of doing a book where the editor has a very small role in it, but it's not as simple as Marvel vs. Image.

HMS: Two things that come to mind as factors that might influence things are, as you mentioned about the production line, if there's not someone overseeing that, given any book, there are dangers that it will never see completion or it won't meet with fan expectation. If there are people, for instance, who have backed a Kickstarter, and they are waiting for something, and you get way behind on fulfilling your Kickstarter to supporters, fans lose interest and faith in that product.

I was just looking at a Kickstarter last night that had caught my interest and I was writing about, and I noticed that they did list an editor credit on their project, which I don't always see with Kickstarters. I thought to myself, "Well, that's kind of reassuring to help with scheduling and fulfillment".

The other things I was thinking, though, is that this issue of whether to have a designated editor on a creative team might be influenced by the degree of experience from the team. If they are totally new to the process, it might make more sense to have a more experienced person there in an advisory role.

SA: That can certainly be the case. It's also based on just what you want to do. With Matt Fraction and Kelly Sue DeConnick, they have all the experience and knowledge, and can do it themselves if they want to—they were doing it all themselves. But they've evolved Milkfed Criminal Masterminds to include editorial staff. They hired Lauren Sankovitch, a former Marvel editor who has tons of experience. It simply makes more sense, in their case, for Matt and Kelly to focus on writing and let other people work with them to get the books out the door. I'm sure they cede no creative control. In my own case, when I was a self-publisher, I credited an editor on those books, but his role was to give me feedback on the scripts. Then I'd decide what to do with that feedback, and do everything else on the book myself—all the parts that I now think of as the editor's job—running it through production and printing, doing all that side of things. The role of the editor can cover a lot of different things …

Sometimes we're just maintaining communication between the different members of the creative team. It can be handy to have someone in the middle, even if the collaborators are old friends—even if they own the material together. You run into problems when either the writer or artist becomes the point person on the book, the driving force—the editor on the Image book—who's having to crack the whip or provide feedback to their own collaborator. It can be tense if the writer is the person asking the artist to get their work in more quickly. If that writer writes some mind-numbingly long panel descriptions, and then is also saying, "I need it by Wednesday," the artist at some point might be saying, "To hell with this." In some sense the editor gets to be "bad cop" because it's not good for the collaborator to be "bad cop." It doesn't help the challenge of making a work of art together.

HMS: I'm aware that this isn't the same for every project, and I actually do fully agree that each project is different in its dynamics, but what do you think the value is of having someone there who is not one of the storytellers? Someone who is not so emotionally invested in the story that it might be overwhelming for them?

SA: That's a big part of how I look at my job. I do get deeply invested in my books, but there is a distance. If nothing else, the editor can serve as a first reader. It's my job to try to be objective. If I read this script or draft, I can say, "I have no idea what's going on on pages 4 and 5,"—or, worse, if I think I know what's going on on those pages, but I'm wrong. If I can give that back to the writer, and they trust me to some degree, that's good. If they say, "Well, you just don't get it," I can say, "Well, I'm reasonably intelligent, and I'm probably paying closer attention than the 'average reader' might, so if I didn't get it, maybe there is some need to make sure your intention is coming across."

I was talking to my son the other day, and he had this idea for a story where he didn't reveal the name of the character until two thirds of the way through the story. Then the character's name gets introduced in a particular way. The name was "Chuck," since Sid is a little obsessed with Fight Club. I won't let him read it yet, but he's in love with Chuck [Palahniuk]. So the main character's name is revealed as Chuck during a fight two thirds of the way through the story. It just gets shouted out in the middle of a bunch of characters. I said, "The reader might not understand that Chuck is the name of the main character. It could be anyone's name in that scene." And Sid said, "I don't mind if they don't understand that." I had to back off as a parent for a second and be a decent editor. I had to say that his intent is what matters and if he's okay that the reader's confused here, so be it. I'm a big David Lynch fan, I should be able to roll with a little bit of confusing the reader, and I have to give my son room to figure that out for himself.

HMS: That's a very tricky situation! Having your own child who's asking your advice as an editor about their storytelling!

SA: And he'll evolve and figure that out, as we all do. It was just that at that point, I needed him to understand that he might be confusing the reader. To which he replied, "Sounds good." So I had served my role as first reader. And often, I think that's all the editor needs to do. If the writer or the artist know the goals they are going for, I can give them some objectivity on whether that intent is coming across. I think that's useful. There's plenty of talent out there who have utmost control over the craft, and don't need feedback, but probably the vast majority of us could use it.

HMS: What do you think contributes to creating an environment of trust between an editor and a creative team on a book?

SA: The obvious answer is "listening." You have to make sure everyone is listening to each other. I can't just bite your tongue or tap your fingers and wait for your turn to talk. Mignola told me that one of the things that he liked about working with me was that most of my editing comes in the form of a question. Like Jeopardy. I don't say, "Mike, you need to do this. We need more robots." I ask questions, and sometimes they are leading questions, and sometimes I know the answer. But it's still important to get the answer from the creator. It's really different from team to team, but the team is everything. One of the most important things about putting a book together—and I can't pull this off on nearly every book I do—is putting together a team that's really going to work as a team.

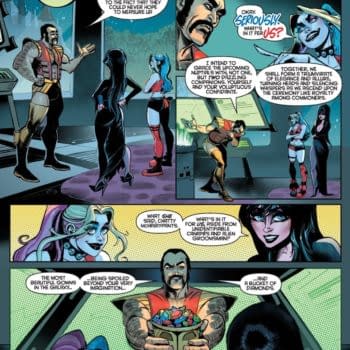

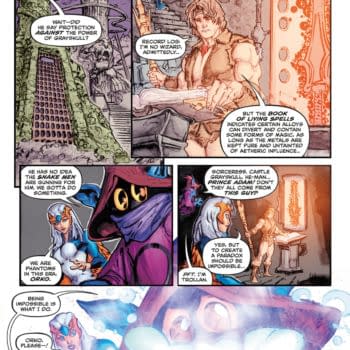

One of the best experiences I've had putting together the team was on Umbrella Academy. And I knew I needed to do exactly that again when I was putting together the team on Fight Club. It's no coincidence that the colorist and the letterer on Fight Club are the same as on Umbrella Academy. Those two guys—Nate Piekos and Dave Stewart—I'd love to have them on my team every time. And I really wanted them to be part of the chemistry of Fight Club. Dave is one of my best friends anyway. Around the time I was secretly talking to Chuck, I saw Nate tweeting something about Fight Club or one of his other books. But the big magic piece of the puzzle, without which none of it would have worked, was Cameron [Stewart]. David Mack and Chuck already had a long friendship and David was involved at an early stage, but the most significant piece in my mind was filling that interior artist slot. We just couldn't have done any better than Cameron.

To get the team really working together, we got Cameron to come to Portland, which really helped set the stage. Dave Stewart was here, Chuck's here, David Mack is here sometimes—Cameron lived in Berlin at the time. He said, "Why don't I come to Portland for a few months?" and that meant we could get the whole team together, spend time together, and build a lot of trust in the collaboration.

With both Umbrella Academy and Fight Club, everyone involved kicked in ideas. Nate did the logo on Fight Club, and hearing where Chuck was going with it, Nate, Dave, David, and Cameron all contributed ideas that shaped the book, even impacted the story, as Chuck kept rewriting while Cameron was drawing. This book would be different without the ideas from any one of those people.

HMS: This is a really interesting question that's very pressing right now, and I'm asking from having visited studios and often interviewing many members of a particular creative team, as people command their own projects, they are faced with a series of choices of how they put their teams together. Sometimes it's within their own studio or within their own vicinity and people either know each other or can meet in person. It's increasingly common, though, for people to find talent through the internet. I hear a lot that someone has found an artist through Craig's List or an art-specific site.

Everyone tends to encourage each other to do that if they hit a brick wall on a project and can't connect with an artist, or colorist, or letterer, to try to connect through the internet. And many times it's a very successful approach. But then the team has to make decisions about how they communicate and how well they try to get to know each other. It seems to me that when you're undertaking a comics project, even if it's just a single issue, you're kind of putting yourself in a situation that's like going into war with a group of people. So you do need a pretty solid foundation of communication.

SA: Yes, yes. I'm kind of old and don't use the internet that much. I don't use Skype or IM that much, so I don't have a strong opinion on the role of the internet or long distance collaboration—I know that people younger than me are probably more comfortable doing chats than meeting face to face. The means that they use probably work fantastically for them. The one hiccup with Umbrella, on those first series, was that [Gabriel] Ba was in Brazil and Gerard [Way] was constantly on tour. He's in Russia right now, in fact, as we work on Umbrella series three. Gerard and I work pretty closely on scripts, and we were on the phone a lot throughout the first two series. We didn't have as much interaction with Ba as we would've loved to have. But the time we got at conventions, or when Gerard was on tour in Brazil, reinforced this bond that's now bone-deep. It was incredibly valuable time together.

I did a convention in Sweden a couple months ago and Fabio [Moon] and Gabriel were there, so we got to spend a whole lot of time together, and it just recharged my batteries in such a great way. It really helped us gear up for getting into the next Umbrella series, which we're well into at this point.

That face to face time is incredibly important, and it's nice to be able to take that into account when putting together a team. When working with the Fiumara twins on Abe Sapien, they're in Argentina, so I don't get to see them much. I was lucky that shortly after starting to work with them, I was invited to a show in Argentina and got to spend time with them. It built a foundation of working together that is still valuable. It's been two years since we were all in the same place together, but the working relationship has only gotten better as it's continued to evolve.

HMS: Yeah, I've just been aware occasionally from watching indie projects form and develop that sometimes creators who are new to this process are under the misconception that it's going to be as simple as a production line. They think as long as they hire someone to do this task, and someone to do that task, that it's somehow going to magically come together and be perfect with no further communication. But if you literally do not know each other at all, problems are likely to arise.

SA: One way or another, there is some kind of chemistry. Good chemistry or bad chemistry. Chemistry built directly out of personal interaction or otherwise. And a good editor can help to massage that. But also just choosing well has a lot to do with it. Bob Schreck told me that 80% of the job of the editor is done when you've put the team together. Well, he said something like that. It was like twenty years ago. I might have revised that in my head …

I know that for Mignola, when he co-writes a book, he can't just be paired with anyone. For one thing, he loves getting on the phone and working that way. Not everyone does. The relationship between Mignola and [John] Arcudi is built on being such good friends, and they work in a particular way. Now that Arcudi is moving away from working on the B.P.R.D., there's no way that I can just drop someone into that role simply because I like his writing. It would never work. There needs to be a new chemistry, and a new way of working together. As you said, you're not just dropping workers into an assembly line, and everyone involved is going to shape where the thing goes creatively.

HMS: That's another challenge, when a team has been working very well for some time, and the book has been successful, but then one member of that team needs to move on. Trying to decide how to switch that person out while still maintaining momentum and letting the new person bring something to the team. It's like when one member of a successful band leaves, and it could go very wrong and cause the band to break up.

SA: Yes. When Guy Davis stepped away from the B.P.R.D. it was complicated like that. He had been so involved, and so prolific. When he decided to move on, we couldn't just find someone who was going to be Guy Davis in any way, shape or form. We couldn't find someone who was going to design the wealth of things that he did, or crank out the pages that he did. So everything changed. Some Mignola fans didn't like the change, but it resulted in us bringing in a lot of different artists like James Harren and the Fiumara twins, and they reshaped not just how the books look, but how they function, how we'd be telling stories over time. On the one hand, none of them were as fast as Guy, which resulted in having many artists to keep up the same number of books. But then with those other artists, we wound up doing some more books. It opened doors because previously we'd really respected the notion that Guy was the artist on the line, with an exception here and there—but now there were a lot of different artists, allowing us to do a lot of different books. We weren't at all eager to see Guy go, don't get me wrong. But it was an evolution. We could have collapsed when he left—and I think we actually did collapse for all of about five minutes, and lament that we'd have to learn how to do it all over again. But we did learn. And now we do it differently than we did then. And now with John Arcudi leaving, it changes again. It ends, and then it starts again, like Brando said in "Last Tango in Paris."

HMS: It's having to look at a difficulty, or a transition, as a new opportunity, and that's hard but can make a big difference. That's the way to save the day.

I remember you said in an interview quite awhile ago with me that you were working on the Aliens/Predator series and you found out that you'd have to totally rewrite it after a lot of progress. There was a big meeting where everyone had to go back to the beginning. I realize that so much was riding on that so that you kind of had to find a way to continue no matter what, but what's the editor's role when something massive like that happens?

SA: That was a unique situation in that we were having this meeting at my house, and the whole editorial team and the five writers, Kelly Sue, Chris Sebela, Chris Roberson, Paul Tobin, Joshua Williamson, were all there. We were pretty far along, had two issues drawn and several scripts written and approved, when Fox pulled the plug. So part of the editor's role there was keeping everyone from blowing their brains out. Or from walking off the project.

HMS: Yes! That.

SA: We found out from Fox on a Tuesday, and we happened to have a dinner planned for Wednesday, so we waited to tell everyone in person at one time. The editors all came and waited for the writers to arrive, and then we told them. We knew that any of the writers might just quit—someone we'd be working with for months on this story might just go. They'd have been within their rights, in my mind. So one of the editors' responsibilities there was to keep hope alive and try to get everyone to stay. Part of our success was that we had created a good team between the five writers where nobody would have wanted to quit, I think, because they didn't want to let each other down.

And before that, of course, the editors had to push back a little bit, get as much clarity as we could from Fox on what we could preserve. Then we presented the news in the parlor of the house. Then we moved over to the dining room table, and everyone was crestfallen to different degrees. Often in those meetings, it would be myself and Kelly steering things, warming the room up, and here we were doing that job again. But we got it going, and in that first night, we had solved many of our problems. Everyone kind of agreed—and I wonder how much this was a defense mechanism, like babies being cute so their parents don't eat them—but we decided that what we came up with that night was better than what we had before. Maybe creative people have to tell themselves that so they don't slit their wrists, but we believed it by the end of the night, and it was a great moment of team work.

HMS: That stands out for me still as one of the scariest stories I've heard in comics. Having that much completed and ready to go and being told to stop and go back to the drawing board. You pulled it off, but the experience of that is terrible. So maybe the editor who preserves that insane optimism to keep going, but also has to be the one who mentally prepares, realizing that some things are going to go wrong. You have to be ready for that.

SA: That's one of the things when putting a team together, or doing any hiring. If you have any degree of experience, you know that something is going to go wrong at some point. If you're doing a project that lasts more than a couple of days, at some point there's going to be a tense moment, and you need to pick who you want to be with in a tense moment. That's one of the reasons it was so easy to go to Dave and Nate for Fight Club, because I know that they are going to deliver at the Nth degree, and who else is going to be able to do that? You get incredibly talented, highly motivated people on a team and you know you've hit the jackpot.

HMS: Now, Fight Club is a very interesting case example. Because on one hand you have a known literary figure with an immense fanbase who wants to do a comic, which seems to be a no-brainer, you've got someone like Cameron who did try-out pages for free and was willing to come out to Portland, so highly motivated for the project, but on the other hand, Chuck had not worked on a comic before and was very concerned about making sure that the content suited the medium. What were the unique issues to address editing Fight Club?

SA: One of the reasons that Cameron was the right guy was because Chuck had not written a comic before. When I first met Chuck, he handed me the script for seven issues of the comic and it was a lot different than the book that we wound up doing. It was complete in seven issues at that time, whereas now it's a ten issue series. The main character's name was different and there were other differences. But reading it gave me an idea of where he was going with the story. I've worked with many writers who weren't necessarily comic book writers when I met them, like Joss Whedon, and Gerard [Way]. Great writers, but somewhat new to working in this medium. So I've gotten to work with amazingly talented people, who I want to be deferential to creatively, while helping them do the best job they can. One of the things I learned long ago about working with a writer knew to comics is that you're making it easier if you hire an artist who can also write.

HMS: Oh, that's interesting. I hadn't really thought of that. Yes.

SA: That's part of what made Ba perfect for Umbrella—he's a storyteller who can solve any problem. With Fight Club, with Chuck, not out of any weakness, but out of ambition, Chuck has thrown outrageous storytelling problems at Cameron. And Cameron is just a genius. I don't know that there's a better cartoonist in the world than Cameron. I'm not saying he's #1, but he's in a rare class of cartoonists, in my opinion. I put him up there with Mignola and with Ba and Moon. These guys do something magical in telling stories with pictures.

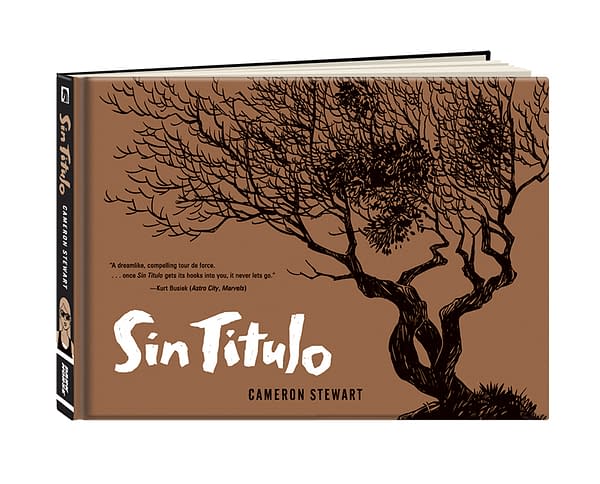

I felt like there was a lot of Chuck in Cameron already. Sin Titulo, the webcomic Cameron did that we published in a hardcover, is an amazing dream-like, David Lynch-like, nightmarish comic. I saw a certain surreality that reminded me of Chuck, though I doubt Chuck would call it that. But Cameron's got that in his work, at every level. If I had had to hire someone to write Fight Club 2, someone other than Chuck, if this had been a licensed comic, I might have hired Cameron. He is the guy who could deliver this thing, in so many ways.

When we were starting on Fight Club, when I'd proposed Cameron but we hadn't agreed on him yet, Chuck and I spent some time in a comic shop, and dug through a lot of comics. Over the course of that day, I realized that if Chuck could draw, he would wish he could draw like Cameron. That was the clincher in why Cameron was the perfect guy.

SA: You're getting a supremely talented creator on a project who isn't going to have to reinvent himself to be part of the vision. He's going to deliver the vision. I couldn't have gotten Sean Phillips and said, "Make it more cartoony." That was one thing I saw that Chuck really preferred in artwork, some cartooniness. So you get someone who does that naturally, and they're naturally right for the thing you're doing.

Umbrella Academy was like that, too. If we had gone with standard superhero art, it would have been very different. Instead we went with Ba, and by going so far away from superhero art, we were able to create the vision for Umbrella Academy.

HMS: That kind of sends a chill up my spine of dread, thinking of what could have happened if Umbrella Academy was drawn in an overly-rendered, muscular superhero style!

SA: Well, there was one thing we did for fun, because Gerard is good friends with Jim Lee. Jim drew a wraparound cover for the series, so there you can see see this other version of what the book and the characters could have been.

With filmmaking, you're still starting with photography, and maybe you're using a team of effects guys to turn it into whatever vision you want. Reality, in the form of photography, is filtered through the director's vision. But in a comic, as in Fight Club, every scrap of reality on each page is being imagined by Cameron—and a little bit of it by Dave Stewart, and a little bit by Nate, and at least once, by David Mack. But the vast majority of it is Cameron—created from scratch by Cameron. The entire reality is Cameron's reality. If you dropped Francesco Francavilla in there, who was another artist we talked about on Fight Club, it would have been a very different experience.

HMS: That's pretty mind-blowing. I tend to think historically, and I think it is possible that a hundred years from now, people may still be reading that Fight Club comic. Does it ever influence you, realizing that you're influencing that experience?

SA: The one time that thought entered my mind was when I was editing Conan a while ago, working with Kurt Busiek. I realized Conan had been around for 70 years at that point, and had been so important to so many generations. There was the Howard prose, then Frazetta, then Barry Windsor Smith, then John Buscema—and then we had Cary Nord. And that is one of those versions of Conan that I can hope will be around a lot longer. It was a fun and amazing privilege to be part of that.

And being involved in Fight Club is a privilege too. The designer, Rick DeLucco, who does the design work that Nate Piekos doesn't do for Fight Club, he's a guy only a little younger than me. One day we were standing outside. I said, "Can you believe we are part of putting together the sequel to Fight Club?" And he said, "I know! It's crazy!" I've been in the job 21 years now and I can still be giddy at the thought of, "I get to be a part of this thing!" Some of these things are really an honor.

I feel the same way, obviously, about the Mignola stuff, which has been the defining aspect of my career, and I feel the same way about Buffy. In some small way, Buffy wouldn't be what it is today without some work I've done with Joss [Whedon], for better or for worse, depending on who you ask. But contributing to something like that, that means so much to some people, is a great opportunity.

HMS: That's another property where you're literally writing the history of characters beyond the previous incarnations and you're so far down that road, that you might get beyond the actual duration of the series in comics. Do you ever have moments of breaking out in a cold sweat and thinking, "I have to make this decision," and you're hesitating a little on the direction of major properties?

SA: No. I think you'd be thinking wrong if you worried in that way. You worry about your creative choices in their context. But if you're asking, "How does this affect the legacy of Fight Club?" you're thinking about the wrong thing.

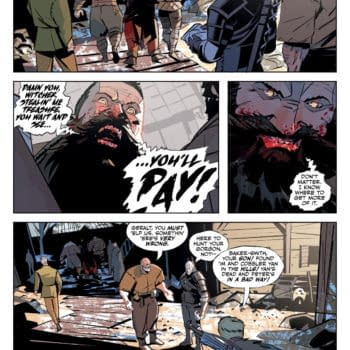

SA: When Fincher was promoting Gone Girl last year, he was talking on NPR, and was asked if he could ever see himself doing a comedy. Without a pause, he said, "Fight Club's a comedy." A lot of people don't get Fight Club, in my opinion. It's not a satire, it's not a parody, but it's something else entirely. It's certainly not a celebration of male rage, the way that some people might think it is. I think some people look at that film, and think, "Brad Pitt's all beat up and sweaty, and he's got sexy abs. That's awesome!"

HMS: [Laughter]

SA: It sure as shit isn't what the book or the comic is about. Chuck hit the jackpot working with Fincher on that film, but the film is different than the novel, and maybe it's easier for people to misunderstand. That's one of the things I was worried people might be upset about going into the comic, that there isn't a lot of fighting, since that's not really what it's about. I wondered if we were going to encounter a lot of dudebro fans who just didn't get it. In my experience so far, I haven't encountered any. Chuck has a tremendous following who, for the most part, really gets his work, which has only gotten more interesting in the past 20 years. Fight Club 2 is not the book he would have written in 1997. He's evolved in interesting ways, and that's the man who has written Fight Club 2. If a person who saw the film and is excited about the fighting sees this comic, they might not get what they're expecting. But Chuck's fans all seem to be pretty darn happy.

HMS: I think in my interview I did with Cameron about Fight Club 2 awhile back, he said that he felt Chuck had incorporated the experience of the effects of the Fight Club novel and film on culture into the writing of this book. And also I realize now that he was hinting that Chuck was going to incorporate himself as a character into the book as well, that the persona "Chuck Palahniuk" is part of all this cultural mythology. Because the comic is addressing the real-world impact of Fight Club in a kind of dialogue and talking to the reader.

How do you think this book engages differently with fan culture than some of the other books you've worked on?

SA: Completely. Where do you start? I've worked on material that has broad social appeal, like the Buffy stuff, Mignola stuff, and Conan stuff. It reaches deep. Working with Sergio [Aragones], too. I've been allowed to reach deep into a readership and a fandom that's been around sometimes longer than I've been around. Buffy really says something about and for the culture in a really important way, and it's been a huge honor to work with Joss on that. His body of work overall adds something to the cultural dialogue, in a way that I feel really good about.

But Fight Club grabs the throat of the cultural dialogue and shakes it around…

HMS: [Laughter]

SA: …like nothing I've ever worked on has. Not to diminish Buffy, but it's of a different style. I think what Fight Club means to people, in an intellectual way, is different than Buffy, which maybe means things to people in an emotional way. And Gerard's work, too, hits people emotionally. Working with Gerard involved meeting so many teenagers who would say that his work has saved their lives. I've heard that sincerely expressed with Joss's fans, too.

SA: Yes, well, it's because of the nature of Chuck's relationship with his audience. It's pretty easy to get people onboard with that kind of thing. One of the things that I took seriously as the editor on Fight Club was making sure that anything we did accurately reflected Chuck's vision. That's one of my favorite parts of the job, the most sacred thing about the job for me. If I'm working on a Witchfinder comic spun out from Hellboy, with which Mike might not even have a lot of involvement, I'm still trying to execute Mike's vision through every part of the process. Even if we're doing a booth graphic, like at New York Comic Con, I'm trying to make sure we're reflecting Mike's vision as best we can without him having to do the work himself.

So, with Chuck, when one of our guys came up with the marketing idea of the social media campaign, one of the key parts of it was tweets from Tyler.

And I knew that nobody could ever write a tweet from Tyler except for Chuck. If you're just linking to an article or showing an image, that's fine, great, do a hashtag and informational text. But if we're ever writing anything in Tyler's voice, that has to be from Chuck. And that means we have to get his time to do it. We have to protect that vision and don't water it down. To make sure we don't turn Tyler into anything but what Chuck's intention is.

SA: We wrestled a little bit with the very apparent reality that Tyler wouldn't use Twitter. That was the first thing we had to deal with. That led to asking exactly what kind of tweets Chuck would write. He gave us a series of emails, and it was like, "Okay, if Tyler tweets, it's in the form of some kind of upsetting haikus."

HMS: [Laughter] That's awesome.

Fight Club 2 returns with Issue #5 on September 23rd.

Abe Sapien returns with Issue #27 on October 14th.

Umbrella Academy: Hotel Oblivion is underway.