Posted in: Comics | Tagged: art, brian bolland, Comics, lichtenstein, sharon moody

Seeing Sharon Moody's Work For Myself by Scott Edelman

Scott Edelman writes for Bleeding Cool;

I headed to Manhattan Saturday for a visit to the Bernarducci Meisel Gallery so I could see for myself those Sharon Moody paintings which had so ticked me off three weeks ago. Would experiencing the real-world art hung on a gallery wall, as opposed to seeing them diminished into relatively small .jpgs, change the way I felt? Would attempting to see the artwork with the guidance of gallery director Frank Bernarducci lessen my irritation about what I saw as an obvious attribution issue?

I believed both the art and the artist deserved a shot at changing my mind, so it was worth a trip before the exhibition closed, which it will do on the 15th. So if you want to see it yourself, you'd better hurry.

[And since I don't want to recap everything I've said before, if you have no idea what I'm talking about, and want to catch up, check out this, this, this, this, this, and this, in that order.]

But first, before diving into the visit itself … a tangent.

One reason I'm sensitive to this issue is because the artists whose work has been repurposed here are more than just names to me. Sure, some of them I may know from their work only (albeit work that affected me deeply and helped transform my life), but there were others who were far more than that to me. I worked alongside many of these creators during my days on staff at Marvel Comics (and yes, that's what I looked like below, seen with my then-future wife in photos from the 1975 Marvel Comics Convention program book) and later as a freelancer for both Marvel and DC.

So I think of these people as friends and colleagues. And when I see an image by Jack Kirby or Ross Andru or José Luis García-López (the last of whom actually drew one of my own stories) or any other comics creator used without even a tip of the hat, I take it personally.

Ironically, even the gallery visit itself was personal. Because 37 West 57th Street happens to be only a block and a half away from 575 Madison Avenue, where I spent so many years working for Marvel during the '70s. Whenever I'm in that part of midtown Manhattan, I usually pause in front of the building to remember of how my life was changed there. So you can see how wading through the geography of comics past to speak up on behalf of comics past might have gotten me a little verklempt.

But enough misty-eyed nostalgia …

The first thing that jumped out at me after being buzzed into the gallery by Associate Director Marina Press was an unmistakable Ross Andru Superman staring up at me from the cover of a flyer about the exhibit. (That's the front, the center spread, and the back of it below.)

Next to the pamphlet was a price list revealing that most of the paintings had already been sold, with just a few remaining. And it turned out the piece which had appeared in the ad that originally alerted me to the existence of this series of paintings, "Mjolnir—To Thy Master!" (based on a page drawn by Kirby and Bill Everett), was still for sale.

Did I buy it? Constant reader, I did not.

Because to be honest, given the choice between spending $7,500 on the image above, and $7,170 for the original page of art below which sold last month from the same issue of Thor, well, you know me well enough to know which I'd have chosen, right?

Which, I think, gets us to the crux of the issue. (And I'm getting to it, don't worry. I'm just taking the long way around.)

Also on the front desk, next to the pamphlet and the price list, was a multi-page statement crediting the original creators from whom Moody took her inspiration. (The copy at the desk, as opposed to the one at my link, was printed on gallery letterhead.)

Marina then invited me to wander the gallery and examine the paintings while she raised Frank Bernarducci (who couldn't be there Saturday) via Skype.

To give you an idea of what the paintings looked like on the walls of the gallery, check out the image below, from the Bernarducci Meisel site. That's a Moody on the far right. (I'd share pics of my own, but oddly, I didn't even try to take any. I wouldn't have snapped without permission, and I didn't bother to ask. I guess I felt any images I took wouldn't contribute to making my point.)

Once I'd had a chance to take in all the paintings, I sat behind the reception desk with Marina and chatted with her and a Skyped Frank, and had an lively and fascinating hour-long talk. We discussed the centuries-old tradition of copying in art, high art vs. low art in cultures past and present, and many other factual matters on which we found agreement. But when it came to what we each thought some of those factual matters meant, and what actions were then required of us, our opinions varied.

So while I learned that both Frank and Marina are reasonable, intelligent, knowledgeable and personable people, and while I appreciated their enthusiasm and their willingness to engage with this visitor from an alien world, I also saw that when it came to the central issue of what Moody added to the work of the original artists, we were never going to see eye to eye, and would just have to agree to disagree. Because in the final analysis, standing face to face with the original paintings, while an interesting experience, didn't alter my reaction to the images or change my opinion about what had been done.

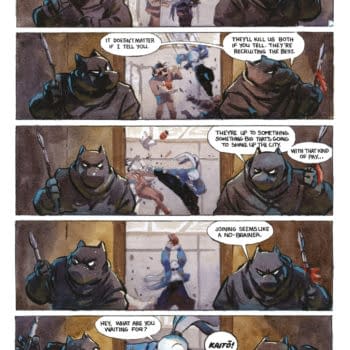

One way to explain this is by comparing Sharon Moody's "You Haven't Left My Side All Day!" (below left) with the original page from Superman #204 on which her painting is based, with pencils by Ross Andru, inks by Mike Esposito, and words by Cary Bates (below right). (Which I chose not because it's a better example than any other pairing, but because it's one for which the original inspiration is easily at hand.)

When I look at the Moody painting, which I can't deny is a spot-on recreation of the original, showing a high degree of craft as she adds three-dimensionality to her trompe l'oeil image, what power I see comes entirely from the art she chose to redraw, not from her stopping a moment in time as a page is being turned. Those at the Bernarducci Meisel Gallery, however, feel that something so transformative has occurred that the strength of Moody's painting comes primarily from her treating the comic as a three-dimensional object.

But I can't see it that way. (And that's fine. After all, that's why they have horse races and why Baskin-Robbins makes a bazillion flavors.) To my mind, it's Moody's choice of that specific page by those specific artists that turns "You Haven't Left My Side All Day!" into something worth looking at, rather than its trompe l'oeil presentation. The heavy lifting here is being done by Andru and Esposito and Bates, without whom, regardless of the talent it took to make the new piece, there'd just be no there there. (Which makes me extremely glad that Saturday's conversation wasn't with Frank Bernarducci's partner Louis K. Meisel, as the divergence of our opinions on the virtue of these types of paintings would be even more extreme, considering that according to the gallery's site, "In 1969, Mr. Meisel coined the phrase Photorealism and became a pioneer of Photorealist art.")

But that's not really the point of all this, is it? Because whether or not I think these paintings are transformative is a matter of taste. Whether you and I agree on the success of these paintings isn't really the issue, and I'd never have raised the matter in the first place if it was just about that. To my mind, it's always been about what one artist owes another, and about the answer to a question Frank put to me, which was, well, what IS the necessary level of attribution in a case like this? What's the right thing to do? Do we need to have a notice attached to every painting? What sort of attribution would satisfy me?

I didn't formulate an exact answer in the moment, but one thing I did realize as I wandered off is that in this world in which thanks to the Internet, anyone can step virtually into the Bernarducci Meisel Gallery—and Sharon Moody's site as well—from anywhere in the world, it's insufficient that the only attribution to the great artists who went before be on a few sheets of paper only to be found on a desk on 57th Street in Manhattan. A trip to New York shouldn't be a requirement to discover that list of names. Virtual visitors will far outnumber the flesh-and-blood patrons who'll ever see the paintings, and there's got to be some way for those folks to be told what's going on, too.

So while I'm thankful to Frank and Marina for the warmth of their hospitality, the rigor of their intellectual jousting, and the grace with which they handled our disagreements, I do truly believe that in an ideal world, yes, every image should have some sort of attribution that indicates, via an unobtrusive placard, what it is the viewer is seeing. Here's a quick and dirty example of what such a thing would look like in a gallery, with a reproduction of the image and the relevant data.

To my mind, this sort of thing would serve two functions. In addition to giving the needed nod to those who created the original imagery, it also helps the audience to understand what's going on with the trompe l'oeil of each new painting. And what I mean is—

Everyone knows what a Hershey's bar looks like. When a trompe l'oeil painting is created of one, as Moody has also done, there's probably no one on the planet who won't immediately recognize it and be able to judge whether or not the artist nailed it. We're all able to say, that IS (or isn't) what the wrapper looks like, that IS (or isn't) the way the chocolate squares look, and so on. We're all equipped to judge without having to do homework. But in looking at this series of comics images, no one—other than, well, me, and those knowledgeable comics geeks who are like me—will be able to ID the original and have any idea whether or not the artist pulled it off.

It's like the comedian (and I'm forgetting his name and failing in my own attribution here, so help me out, please!) who would get on stage, announce he's going to do an impression, and then instead of doing Cagney or Bogart, proceed to ape someone the audience doesn't recognize. And then reveal, well, that's an impression of Uncle Murray (or something like that), and say that if you knew his Uncle Murray, the impression would have KILLED.

When it comes to Moody's paintings, I feel like the comics-related ones are Uncle Murray. Which is really stretching a metaphor, but in terms of aping something of which an intended audience has no knowledge, it's a metaphor I think bears stretching.

Attribution would make things better for all concerned—the original artists, who deserve recognition, the potential audience for the paintings, who'll better be able to judge what's been done, and the artist and curators, who'll have done the right thing.

With this current exhibition ending a week from today, though, I can't see such a thing happening out in the physical, flesh-and-blood world, but it is something that should be kept in mind for any future gallery show, or for when a museum picks up one of these paintings for its permanent collection.

However, I still believe that in the virtual world, where these paintings will live on, and where we're all spending so much of our lives, explicit attention must be paid. Because unless something is done there, come the 16th, once the physical exhibition vanishes, those few sheets of paper currently on that desk on 57th Street will vanish as well, and visible attribution of any kind will no longer exist. And that would be wrong.