Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: captain marvel, Comics, dc comics, entertainment, gabriel rodriguez, He-Man and the Masters of the Universe, idw, judge dredd, keith giffen, Little Nemo: Return to Slumberland, Monster & Madman, steve niles, The Delinquents, valiant entertainment

Thor's Comic Review Column – Judge Dredd, He-Man And The Masters Of The Universe Vol. 3, Monster & Madman, The Delinquents, Captain Marvel, Little Nemo: Return To Slumberland

This Week's Reviews:

Judge Dredd #22

He-Man and the Masters of the Universe Volume 3

Monster & Madman

The Delinquents #1

Captain Marvel #6

Little Nemo: Return to Slumberland #1

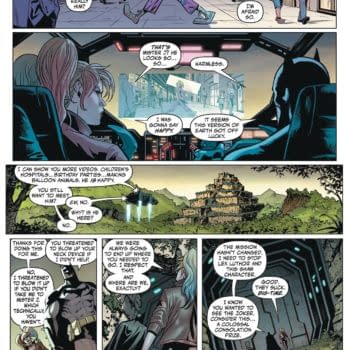

Judge Dredd #22 (IDW Publishing)

By Bart Bishop

Judge Dredd. It's a name synonymous with justice for almost 40 years. Originating in the UK magazine 2000 AD, John Wagner created the character to function as a criticism of American extremism filtered through a foreign perspective, taking the "tough cop" trope to its logical extension and often veering into satire. Since November 2012, however, the American publisher IDW has been taking a crack at Joseph Dredd, with writer Duane Swierczynski at the helm. This version is nearly identical to his counterpart from across the pond, except the tone is a bit more dry and interweaves the social commentary in a more deliberate fashion. This is still Judge Dredd, however, the grizzled lawman living in the dystopic Mega-City One, and issue #22, "Black Light District, Part 1" manages to continue the long-form arc dealing with the Dark Judges, Dredd's arch nemeses including the iconic Judge Death, while still managing to inject a bit of exigency into the spectacle. Artist Stephen Scott is a steady hand for delivering "widescreen" action mixed with macabre imagery, a cartoonish style that disseminates geography and emotion clearly and economically. Accompanied by Swierczynski, they've managed to bring something new to the legacy while paying tribute to its roots, but those roots bring inherent complications in our current political climate.

Issue #22 picks up immediately where #21 left off. Judge Dredd is trapped within Sector One, cordoned off by a mysterious ooze from the cursed earth, being pursued by Judge Death. Judge Anderson, the psychic that was shot "dead" but is actually floating through the astral plane that is Deadworld, is communing with Dredd, providing much needed exposition on how to defeat the 13 Dark Judges (new threats as well as classics including Fear, Fire and Mortis), who are seeking out bodies to possess. Meanwhile, outside the sector Judge Cal has taken this opportunity to declare himself Acting Chief Justice, as the rest of the Council of Five are stranded on the prison moon of Titan. This provides a choice opportunity to riff on current tensions, with Cal initiating a surveillance system that monitors citizens' every move. Thus the police are called in to "subdue and observe until further notice" any degree of crime, from loitering to considering shoplifting to having a poor disposition. Not only is this intentionally echoing the the Patriot Act and current privacy scandals such as the NSA controversy, it inadvertently gets to the heart of what's going on in Ferguson, Missouri at this very moment.

That's the crux of the character that Swierczynski struggles with here, that he's a fascist and a living embodiment of politicized criticism. In the 1970s Wagner was directly responding to the likes of Dirty Harry, whom John Milius & co. had laced with a might-makes-right mentality. The difference is that in that movie in 1971, Harry's conservative attitude and big gun are in direct conflict with his superiors, a police chief and mayor that acquiesce to criminal demands, a prescient anticipation of the political correctness that permeates modern American culture. In Dredd's future, however, his brand of fascism is the status quo, with democratic activists portrayed as fools. How to balance this fine line, with Dredd advocating dictatorship while still being a heroic figure, in the wake of rampant militarization of police forces across the United States? The only answer is the ratchet up the Orwellian bent of Judge Cal to such an extreme degree as to single him out as a bridge too far. The only problem is that, while earlier issues had a Dragnet-esque narration that clued the reader into Swierczynski's intended tone, this issue's straightforward action doesn't leave much room to get the joke.

Stephen Scott, fortunately, is up to the task of laying down blockbuster action scenes. Taking over for regular artist Nelson Daniel, who provides aesthetic continuity here as the colorist, Scott's thick, sketchy lines provide dynamic movement, and he has imagination enough to imbue vibrant life into cyborgs, demons, punk rockers, and most important Dredd himself. The character's design has remained essentially unchanged since his inception, really only steadily escalating over the years in terms of extreme accessories. Could his shoulder pads be any bigger? What's fascinating is how his design works in contrast to the imitators so rampant in the 1990s, the Cables and Punishers whose writers and artists aped Wagner and Frank Miller like a snake eating its own tail, with it never dawning on them how much they were missing the point. Scott gets it, outfitting Dredd with the perfect amount of iron jaw, tincturing the backgrounds with a degree of detail to make Moebius proud, and visualizing the Dark Judges as creeping Eldritch horrors. The only moment that feels rushed is the last two pages, a cliffhanger involving the Council of Five arriving on Titan that fails to land with any resonance as the danger of the environment and the Judges' proximity to their impending enemies isn't communicated clearly.

To be honest, although I've loved the character for most of my life, I haven't read much Dredd. As blasphemous as it may be, most of my knowledge of the comic character comes from crossovers like Judge Dredd vs. Aliens and Judge Dredd vs. Batman. No, the Dredd I'm most familiar with is the cinematic versions. I'll go to bat for the 1995 Stallone debacle, missing helmet and all, as I think it really gets the heightened sensibility at the heart of "Old Stonyface". Mostly, however, the 2012 Karl Urban joint has my sword, as it's a lean, mean little potboiler. What both do, as a consequence of the translation to celluloid, is attempt to humanize Dredd through a story arc of having him realize the minutiae of human circumstances, the grey between the black and white world of The Law. The former movie is not subtle with this at all with Dredd and Hershey kissing at the end and everything, while the latter handles it with a bit more elegance as the subtle change he undergoes is at the end of the day he passes Anderson when he wouldn't have at the beginning of the day. Due to the nature of serialization, the Dredd of the comics can't afford to change, so credit is due to so many writers for keeping him engaging after all these years, and Swierczynski is no exception.

It's just unfortunate that the real world is starting to look more and more like Mega-City One.

Editor and teacher by day, comic book enthusiast by night, Bart has a background in journalism and is not afraid to use it. His first loves were movies and comic books, and although he grew up a Marvel Zombie he's been known to read another company or two. Married and with a kid on the way, he sure hopes this whole writing thing makes him independently wealthy someday. Bart can be reached at bishop@mcwoodpub.com.

He-Man and the Masters of the Universe Volume 3 (DC Comics, $14.99)

By Graig Kent

A recent article on this very site by my colleague Adam X explored the idea of nostalgia and how it shapes art and pop culture, as well as how it is used to attract an audience. He was doing so in context of the so-popular-that-people-are-starting-to-hate-that-they-like-it Guardians of the Galaxy movie (succumbing to it's-popular-so-it-can't-be-good syndrome), but much of what he writes about extends to comics as well. After all, aren't mainstream comics largely fuelled by nostalgia. If the aging population of comic book readers is what makes up the majority, what are most of us investing in if not our own childhood attachments to certain characters and universes? It's the whole model, hook them when they're young, and try and make a fan for life (or it used to be, the "hook them when they're young" part is far from a priority these days).

Something like this He-Man and The Masters of the Universe trade paperback — which packages the first six issues of the current ongoing into one package (along with reprinting a prequel that was previously offered digital-only) — exists entirely to capitalize upon the nostalgia market founded by the 1980's toy line and cartoons. It's been over a decade since a He-Man cartoon was on the air, and that series did not gain anywhere near the same amount of traction with the youth market as the original 1980's series. I'd even hazard a guess that the bulk of the toys produced in conjunction were purchase by grown men, with intent to collect and/or display, and not for children to play with. Today, the He-Man family mainly has a presence in the collector's market, with $50 action figures and $400 playsets catering exclusively to a fanbase established 30 years ago.

Masters of the Universe comics have been an off-and-on endeavour for some time, including a stint in the aughts at Image, but producing a book solely for the nostalgic can only last as long as it holds the buyer's interests. The cartoons and comics and toys of the 2000's were decent but they captured very little of the flavour of the originating materials, and didn't present stories or characters compelling or exciting enough to compensate for it.

This latest run of Masters of the Universe looked to follow suit. It began at DC as a 6-issue mini-series (collected as Volume 1) and was a troubled endeavour from the start. Writer James Robinson and artist Howard Porter kicked off a direly dull story of Adam with amnesia, and were replaced by the third issue with Keith Giffen writing and Philip Tan (followed by Pop Mhan) on art in an attempt to salvage the storyline. I didn't stick it through as it didn't live up to the expectations of my own nostalgia. But despite the awkwardness, DC stuck with the license and so did enough of the die-hard fans, with a couple successful one-shots and digital-only content (collected as Volume 2) which led into a full-fledged series which has now outlived any previous effort at a Masters of the Universe comic.

Having survived a brutally choppy first run, and with word of mouth spreading about the new book, and a few clever marketing gimmicks to draw attention (a new costume for He-Man, a DC Universe vs The Masters of the Universe mini-series) this old fan felt it time to give it another shot, and frankly, this Masters of the Universe trade is far better than it has any right to be. My daughter became fascinated with He-Man at age 3 and remains a huge fan, so I've been steeped in retro He-Man for over two years, and while it maintains a certain charm, the formulaic storytelling isn't very good (every episode could make for a very entertaining Rifftrax). This series abandons the formula, toys with the familiar, builds characters and shows a world where there are consequences. It doesn't jettison established character so much as recognizes there wasn't much to those characters to begin with.

With this comic Giffen has injected scale, drama, and consequence into He-Man's domain. It opens with a tribute to the fallen Sorceress and Teela still dealing with the knowledge that she was her mother. The focus, however, is on bringing Prince Adam's lost sister Adora/She-Ra into play, not as an ally at first, but an adversary, a pawn of Hordak having been stolen from her home as a child. Where Hordak has evolved into a xenomorphic vampire creature with H.R. Geiger influences, Adora wears armor and a helmet inspired by the classic Hordak action figure, and goes by the apt name Despara. She's introduced attacking farmland, shackling up the farmer while his two young boys lay smoldering on the ground. This book isn't for the kids. Fulfilling Hordak's mission in Etheria, sights are turned to an already-ravaged Eternia, where Hordak opportunistically seeks both power and revenge.

It's upon coming face to face with her twin, and more importantly with Teela, that Despara begins to doubt her mission, her allegiances, and her own history. Giffen crafts a very engrossing tale around Despara/Adora's struggle with identity, and what's more creates a rather amazing dynamic between Teela and Adora that marks the highlight of the book. That the relationship between two female characters is the centerpiece of the story (also noting that the mother-daughter relationship between Despara and Shadow Weaver winds up having equally tremendous importance) in a book that's based off ostensibly a "boy's toyline" and a masculine power fantasy is tremendous, and that he pulls it off so well without succumbing to cliche or making them "men with boobs" is almost shocking, if it didn't seem so effortless.

It's not that He-Man takes a back seat, but he's certainly riding shotgun in this adventure. The focus is less on how the story it impacts He-Man as a character, and more on how Despara/Adora's journey to becoming She-Ra affects this universe they occupy. Giffen also gets just how ridiculous much of He-Man is, but also understands how fans embrace it. Mekaneck, for instance, becomes the subject of Teela's ridicule in the book ("He stretches his neck!") but Giffen still gives the maligned Master his due.

Mhan, for his part, seems fully invested in creating a lived-in Eternia, one that embraces the historical character and environment designs, but also embraces the changes (more than likely handed down to him). He making them work in the fantasy context in which they live in a manner that was unsuccessful in the 2000's effort, moreover he makes them work in the context of the story. Even that He-Man redesign — the ugly red pants-and-shirt one — works within the frame of the story, but thankfully seems only a temporary adjustment. It's still unfortunate, though, that the He-Man redesign works so hard at covering him up, while Teela's redesign has her showing far more skin than she ever did. To Mhan's credit, he never sexualizes the female character in this book, and even Teela's bra-and-underwear scene is less about titillation and more about her "don't-give-a-shit" attitude. Mhan handles the epic scale of the battles immensely well, and one is always aware of the overwhelming odds the Masters of the Universe are facing against the Horde invasion.

It may be nostalgia that gets you in the door, but it's good stories with smart characters, and a sense of respect for both the property and the reader that will keep you coming back.

Graig Kent keeps promising to finish the final edit on that novel, play test that board game, start drawing that web comic, find an artist for that children's book, and maybe write that teleplay, but first he's got to read that pile of comics and watch that backlog of movies…and all that cheese wont eat itself. He's been reviewing things for over 15 years. He's rarely on twitter @thee_geekent, he sometimes writes about movies at [wedisagree.blogspot.com], and his dog has a blog [tacomblur.tumblr.com]

Monster & Madman (IDW, $17.99)

By Cat Taylor

I don't know that I would say there's a horror resurgence in comics right now. After all, the biggest publishers don't seem to be doing much with the genre. However, there sure are a lot of horror comics coming out from the independent and digital publishers. One of the best-known of the current horror comics writers is Steve Niles. Niles is often credited with much of the renewed interested in horror comics. He definitely has a wealth of related material on his resume, not just in comics but novels and screenplays as well. Probably the best known of his work is the original 30 Days of Night comic book. So, if that appeals to you, you may well want to check out this recently issued trade paperback of Monster & Madman, which was released earlier this year as a three-issue mini-series.

Monster & Madman follows the grand horror tradition of monster mash-ups. In this case, it's the story of Frankenstein's Monster that picks up at the end of Mary Shelley's classic novel. In this comic, the monster actually survives the novel's ending and makes his way to London where he meets Jack the Ripper. The tale becomes what Shelley may have produced if she had been asked to write Bride of Frankenstein as a sequel to her original Frankenstein novel. By that, I mean that Niles has written this story with a tone that is truly reminiscent of the original novel rather than being more similar to the many adaptations that take great liberties with the source material. For example, the Monster & Madman story is told from the monster's point of view, mostly through his thoughts about his surroundings and circumstances. As omniscient readers with a window into the monster's mind, we get to witness his thoughts as he learns emotions and experiences things as a new "life" in a world. Unfortunately, he only experiences the worst parts of humanity.

Even though this is a fictional story, the sympathetic part of me actually felt sorry for the monster a few times simply because the author never allowed him to meet anyone with any redeeming qualities. I wonder how different the story may have been if he'd actually met a few nice people. Despite his encounters with so many vile humans, situations occur that reveal that the monster has somehow managed to form a moral code and the ability to tap into complex thought processes. Like in the original novel and in most of the movies, the fact that the monster has a level of morality above most of the other characters is what makes us sympathetic to him. Although in a story where the second lead is Jack the Ripper, it doesn't take much of a moral code to be the "good guy" in the story.

During my first read of this book, I felt like the moments of horror would be truly scary if seen in a movie theater. However, the story proceeded so slowly that it probably would never work as a movie, except maybe for a much older audience that grew up on horror movies which a much slower pace than those released today. Therefore, this material is probably best served as literature. While that literature could just as easily have been a novel, it's the artwork of Damien Worm that adds another dimension to this tale. Worm's style effectively captures the gothic atmosphere that a story like this needs. His work reminds me of the mixed-media art that Bill Sienkiewicz did for comics like Stray Toasters. Although this sort of art is effectively creepy, the one criticism I have is that it occasionally took me out of the story since the abstract nature of the visuals didn't always easily advance the narrative.

If this book appeals to you, or if you are a fan of any of Niles' other work, you may also be interested to know that he and Worm will be releasing a new comic series this Fall called October Faction. Based on what I've seen here, I suspect it will be worth a look.

Cat Taylor has been reading comics since the 1970s. Some of his favorite writers are Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman, Peter Bagge, and Kurt Busiek. Prior to writing about comics, Taylor performed in punk rock bands and on the outlaw professional wrestling circuit. During that time he also wrote for music and pro wrestling fanzines. In addition to writing about comics, Taylor tries to be funny by writing fast food fish sandwich reviews for Brophisticate.com. You can e-mail him at cizattaylor@hotmail.com. He ate chicken nuggets and drank a large soft drink while writing this.

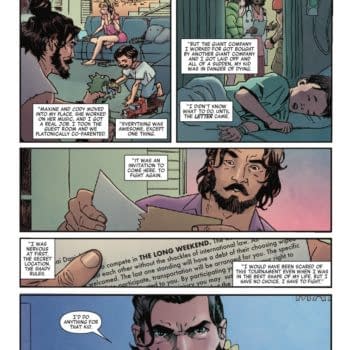

The Delinquents #1 ($3.99, Valiant)

By D.S. Randlett (@dsrandlett)

Whenever I see superhero universes trot out the "New Reader Friendly #1!" issue of an established franchise I always think of a struggling musician trying to warm up an unresponsive crowd. "The jumping on point," when advertised, is usually the mark of desperation for a given title, or else an admission by a publisher that they've been fucking up. See the creative team change on the New 52 version of Green Arrow or the change of Justice League of America to Justice League United for probably the most visible examples of this in recent memory. The fact is, the great comic book runs probably don't need to advertise jumping on points: readers will come to quality, usually. I think back to Neil Gaiman's Sandman, and just how odd it would be to see a "New Arc!" blurb on top of Dave Mckean's art. So, here we are with Valiant's newest series, The Delinquents: a limited crossover between the publisher's comedic superhero titles Archer & Armstrong and Quantum & Woody. Both of these are books that I buy religiously and loved out of the gate, but am woefully behind on reading.

In terms of plot, The Delinquents feels very much like its own thing, and combines the approaches and basic stories of its parent titles quite deftly. But more than that, The Delinquents doesn't feel like a desperate effort to win new eyeballs, but rather a confident celebration of an aspect of Valiant's line that no other superhero line really has in force at present. The superhero comedy book has been a rarity for much of the genre's modern age. While comedy is often present in superhero comedies, it's usually as a seasoning for the big fights and the soap opera. It's rarely the other way around, with a few exceptions (Thinking Hitman and Hercules here). In Archer & Armstrong, Quantum & Woody, and now The Delinquents, superhero tropes aren't parodied as much as they flipped on their head. Instead of jokes serving action and soap opera, action and soap opera serve jokes in ways that are always fun and often surprising. Delinquents co-plotter Fred Van Lente's introduction of The Eternal Warrior in the pages of Archer & Armstrong presents an almost perfect encapsulation of this line's approach. Van Lente never shies away from the serious action roots of the character, but with the point of view adjusted he becomes a great source of jokes by dint of his sheer 90's James Cameron badassery. It's a delicate balancing act: milking great jokes out an otherwise serious (lately) genre while never undercutting it.

Scripting duties on this issue are handled by James Asmus (of Quantum & Woody fame), and he does a really great job of fusing the different feels of the two parent series. Asmus has been writing two of the characters in this series for a while now, but I was wondering how he would handle the duo of Archer and Armstrong, who have been stamped by Fred Van Lente so deeply that I almost have trouble imagining anyone else putting words into their mouths. But Archer and Armstrong feel remarkably consistent here, likely thanks to the collaboration with Van Lente (who gets a plot credit), but the script nails all of these characters perfectly. It also helps that The Delinquents is very funny, and bracingly political. It's one thing to be funny, it's another to have a point, and this book seeks to make a point. Or if not make a point, at least unload on the bullshit that affects us all and provide some catharsis. Putting it down, I was struck by how much The Delinquents felt like a classic LucasArts adventure game.

Kano's art also goes a long way in terms of selling the humor. There are some sequences where he employs some rather odd panel grids in order to play with time and rhythm in order to sell the punchlines. In fact, it's his use of panels that sells the jokes more than his style, which veers more towards realism than the cartoon. As realistic as he can possibly get given the subject matter, anyway. There is a striking amount of pathos in his characters, though, even at their most ridiculous, and Kano's style captures what's been so great about the Valiant approach to comedy storytelling: it's always a balancing act. Kano finds the tension in the writing and exploits it, accentuating both poles here: the humane on on end, the absurd on the other.

D.S. Randlett lives in the hills of Virginia and takes credit for the reviews that his emaciated twin brother writes while chained to the old radiator. He plays his guitar while biding his time for unsuspecting tourists and thinking about going to grad school.

Captain Marvel #6

By Adam X. Smith

If there has ever consistently been a comic that I've had a harder time locating copies of in the week after its release than Kelly Sue DeConnick's Captain Marvel, I simply don't know what it is. This is either a case of Forbidden Planet constantly getting its order quantities wrong, or it's a testament to the fact that this book is enjoyed by so many people.

As the final part of "Higher, Further, Faster, More" opens, Colonel Carol Danvers is facing off against the Spartax Empire's fleet, the one person standing between a planet of intergalactic refugees and the callous indifference of J'Son, Emperor of Spartax (drawn by artist David Lopez as a sort of evil Commander Riker).

I know it's not my "thing" to just enjoy a book for what it is, but it's true – this book just gives me a good feeling. The amount of times I've had to try to dismiss my own indifference to Dan Slott's Superior Spider-Man because I found it too soapy and scattershot made me wonder whether I was being too critical, but reading Captain Marvel demonstrates to me that you can make a superhero soap opera if the character is interesting and does interesting things.

What it also demonstrates is that there's no reason that a female-led book has to pander to gender stereotypes to get a broader audience, just as you don't have to make Carol Danvers mystically pregnant or depowered by mutants or an alcoholic or the archetypal hero of an alternate timeline or wear a skimpy outfit in order for her to be relevant. You just give her what DeConnick gives her here: personality, agency, and a cubic buttload of chutzpah.

Part 6 of this arc doesn't have a ton of stuff going on, but what it has is fried gold. We see the flagship female lead of Marvel comics standing up to seemingly insurmountable odds and preventing the eviction and massacre of innocent lives. The tyranny of J'Son isn't ended but he is dealt a blow to his unchallenged ego and supremacy that takes him down several pegs. Carol's ragtag group of resistance fighters face certain death and survive. In the words of a certain Time Lord, just this once, everybody lives.

And you know what – just this once, I'm fine with that. In a week where an artist I still really want to respect has to stop working because some people decided his reputation needed to be ruined; when American civilians and journalists being threatened with heavy artillery at home and abroad is the price for bringing us the truth; and when a sequel to Sin City is not the first thing I want to see in the cinema when I get paid…

I'll take whatever good news I can get.

Adam X. Smith is a paranoid android from the Planet X. For the last 27 years he has been living amongst the people of Birmingham, England (and more recently the University of Lincoln) ostensibly as a student of the school of hard knocks (also BA Hons Drama), but secretly on a mission to scout out the planet for invasion by alien forces; his weekly communiques on his various blogs are actually highly coded messages to his extra-terrestrial masters. He enjoys the musical stylings of local chiptune-metal band Elmo Sexwhistle, the fiction of Kim Newman, Kurt Vonnegut and Chuck Palahniuk, and his hobbies and interests include film-making, drama, occasional Youtubing, journalism and plotting the subjugation of humanity. He can be found on Youtube, Tumblr, Twitter or by jamming an ice-pick through the optic chiasm.

Little Nemo: Return to Slumberland #1 (IDW, $3.99)

By Jeb D.

Writers who attempt to continue the work of pioneering predecessors will often find that their efforts are greeted less with fulsome praise, or outraged attacks, than with something of a shrug. Whether you're trying to recreate Raymond Chandler's mean streets, Ian Fleming's globetrotting mayhem and womanizing, or P.G. Wodehouse's world of hapless schemes and romantic entanglements, there's limits on just how well, or how poorly (more or less) it can be done: so long as the basic foundation is in place, you're unlikely to have a spectacular failure, but neither will you be able to bring that spark of inspiration that was uniquely theirs; that spark which, each time out, worked some variation on their familiar formula that we wouldn't have imagined. Comic book creators, though, have an advantage over novelists in that respect: while there are real limitations on the rewards possible when imitating a legendary creator's writing style, there are aesthetic possibilities in the art that can dazzle the reader, even without really treading new ground. And while this tribute to the genius of Little Nemo in Slumberland writer/illustrator Winsor McCay, from writer Eric Shanower, artist Gabriel Rodriguez and colorist Nelson Daniel, is imitative rather than innovative … it still looks stunning.

Little Nemo in Slumberland, originally published in the early 20th century as a full-sized newspaper page, was one of the most influential creations in the history of the comic strip: to view its amazing Art Nouveau stylings and innovative layouts today is to halfway wonder if everyone else has been wasting their time since 1905: McCay was breaking the rules of comics paneling almost before they existed, using tricks like having his characters interact with page elements like word balloons, and incorporating his title lettering into the strip itself, before Will Eisner was even born; his ability to control elements of timing, pace, and perception remind us of the similarity between sequential comic storytelling and film… except that McCay was deploying techniques that wouldn't become common in the cinema for decades (to say nothing of the fact that he was evoking a "psychedelic" experience thirty years before the invention of LSD).

In the original strips, Nemo was a young boy, asleep in his bed, whose dreams became weird, fanciful, escapades with a cast of eccentric characters, inhabitants of the fairytale-like kingdom of Slumberland, whose Princess chose Nemo as her favorite playmate. Whether racing kangaroos to the moon, swimming with mermaids, or eluding giant rabbits, Nemo viewed his adventures with a mixture of glee and gentle bewilderment; most strips would end with Nemo, just at the moment of crisis, awakening to find himself on the floor of his bedroom, bedclothes scattered everywhere, pondering his exploits.

As whimsical as the strip could be, with its fairytale-like design and cast of characters, like most great "children's" writers, McCay wasn't shy about giving darker shades to his young hero's adventures: Nemo once destroyed an ice civilization with his tears, and would be threatened with walking a pirates' plank, or being trapped in a giant's birdcage, before tumbling out of bed and waking up.

McCay was a contemporary of L. Frank Baum (Nemo debuted five years after the first of Baum's Oz books appeared in print), and his work shared many of the same influences that marked Baum's storytelling, as well as the visual styles of Oz illustrators like W. W. Denslow and John R. Neill, making Shanower more or less the obvious choice among contemporary writers for this new series, having written literally dozens of comics adapted from Baum's Oz books. He and his art team capture the Ruritanian vision that characterized the look and social structure of Slumberland (and Oz, for that matter), and gleefully recapture McCay's fondness for walking furniture, floating buildings, weird monsters, and courtiers falling all over themselves to please their monarch in a style that mingles Mother Goose, the Arabian Nights, and Harper's Bazaar.

In this new series, our protagonist is young James Nemo Summerton, who, unbeknownst to him, is being recruited to take his namesake's place as the new playmate of the spoiled, lethargic Princess of Slumberland (the time isn't specific, but we are told that the previous Nemo was her playmate "long ago"). In contrast to McCay's original, our young James doesn't particularly like being called by his familiar name ("My dad named me after a cartoon!" he meta-complains), is somewhat suspicious of these dreamtime peregrinations, and is emphatically NOT interested in "playing with some girl." Royal emissaries are dispatched to retrieve young James Nemo, with various fanciful obstacles on the way, and this issue culminates in his first sight of Slumberland, though he remains uncertain about his destination, and suspicious that he's living through something not quite real.

The McCay-style metatextual elements feel right at home here, and Shanower does a good job emulating McCay's writing style. That's definitely an easier task than his art (particularly since McCay was notoriously slapdash about the dialog in his strips), but it's still tricky: we've seen various creators take on revivals of, say, The Spirit (arguably the comic most comparable to Nemo in its groundbreaking techniques), and while some can capture Eisner's look or his voice, what they can't replicate is his context: a modern story featuring The Spirit in his suit, fedora and gloves immediately brands itself as retro, whereas Eisner was spoofing the hard-boiled heroes of his own era. Similarly, a young boy who reacts to weird dreams and tumbles out of bed with a repeated "Oh gosh!," "Whee—what a ride!" or "Yow!", in today's context, feels arch, if not outright contrived; I don't know if young boys of McCay's time really did have such quaint ways of expressing themselves, but I do know that what Shanower is giving us here is a faithful recreation of McCay's dialog, not anything derived from his own specific vision of the characters. It's not a deal-breaker, and occasionally charming, but it does suggest that Shanower's putting as much work into capturing McCay's weaknesses as his strengths.

As to the artwork, I can think of no higher praise than to say that Rodriguez (Locke and Key) and Daniel, with able support from letterer Robbie Robbins, have done justice to the original Nemo. The paneling resembles the later years of the original strip, when McCay reverted to more conventional layouts, and Shanower allows them to pace things briskly: in 22 pages, there's several different attempts to get Nemo to Slumberland, and we're treated to visions of our hero floating and flying, night skies more beautiful than most of us modern city-dwellers have ever seen, clowns, magic elevators, a rooftop loop-the-loop toboggan track (perfectly sized for a boy's bed!), and a gloriously colorful candy-chomping dragon ("The triple-tongued Binthromium!"); it would be only slightly hyperbolic to suggest that the two-page spread of Nemo's first view of Slumberland is worth the price of the book on its own.

Actually, this first issue's a darned good buy on any terms, as it comes loaded with the kind of bonus you'd typically expect to get in a collected edition: a copy of Shanower's script, several pages of Rodriguez' rough pencils, and a reproduction of a classic Nemo strip.

I'm not actually sure what constitutes an "all-ages" book these days. On the one hand, there is certainly no content in this comic that would be of even slight concern to any parent wishing to shield their child from depictions of violence or sexual activity. On the other, the slightly twee charms of the storyline are more likely to appeal to an older comic fan with some sense of the legacy being honored, than a younger reader hungry for a storyline with a bit more urgency, particularly given the reset that happens every few pages with Nemo waking up on the floor. But for anyone moved by sheer beauty in comics illustration, art that evokes one of the medium's rare geniuses, this is an absolute must. And, heck, try it on the first kid you see, too.

Jeb D. is a boring old married guy whose comics background includes attending the very first San Diego Comic-Con, being lectured on Doc Savage by Jim Steranko, and fetching an ashtray for Jack Kirby. After a quarter-century in the music biz, he pursues more sedate activities these days, and will certainly have a blog or Facebook account or some such thing one day.