Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: City Paper, Colonial Comics, Comic strips, Comics, entertainment, indie Comics, Joshua O'Neill, Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream, Locust Moon Comics, winsor mccay

Philly Comix: Talking With Josh O'Neill About Locust Moon, City Paper, Colonial Comics And More

By Nikolai Fomich

Nikolai Fomich: Josh, why do you love comics? What would you say is special and unique about this form of art?

Josh O'Neill: I love comics on such an ancestral, bone-deep level that it's hard for me to verbalize exactly why. When I was a kid the newspaper funny page was a holy place – everything about it seemed like pure magic. Honestly, I liked every single strip. Even the terrible ones. Just the fact of the words and cartoons and jokes made me feel at home. Whether it was Ziggy or Cathy or Peanuts or the Family Circus, it didn't matter – I had my favorites, but to me they were all hilarious works of transcendent genius.

My parents only got the New York Times, so comics in my home were an economy of scarcity. I would save nickels to buy Bazooka Joe gum because I wanted to read the stupid comics on the wrapper. I used to get my grandma in Philly to save the Inquirer comics for me. When we'd visit she'd hand me this treasure trove, and I'd go scurry away and hide somewhere and laugh my ass off. The thing I'm always on the lookout for now is anything that can give me a fraction of the feeling of total pleasure I felt back then, holed up with a stack of funny papers.

For my money, comics – especially when they're the work of a single author – are the best possible way to climb into another person's mind. Cartoons operate on a subverbal level. They transmit directly to your neocortex or something. (I don't know what a neocortex is.) When I read a book like Farel Dalrymple's The Wrenchies, or Chris Ware's Building Stories, or Charles Burns' Black Hole I'm seeing the world through their eyes, their mind, their physical bodies. Their words, their ideas – and the tremble or swoop of their hand, the weight of their line, their eagerness and obsessiveness, their bliss or pain. You can feel it coming straight through the drawings like an IV drip.

There's no place to hide on the comics page. Your fingerprints are everywhere. And the cartoonists whose work I'm drawn to use that fact to deliver something unfathomably deep and true. They give everything they have to the page. They're right there with you.

I think that art is a form of communion, and comics are as intimate as it gets. As a weird, lonely, bookwormy kid, I went to the comics page looking for love, and I found a wealth of it. I keep finding more and more.

NF: Growing up, which comics meant the most to you, and which creators did you find most inspiring?

JO: There were so many. Calvin and Hobbes was my favorite comic then and is my favorite still. The cynicism and sweetness and oddball energy and wonder, the id-driven joy and soulful searching sadness of it. I think I've read every single C&H strip at least fifty times. Bloom County, and The Far Side, and Peanuts. I found Prince Valiant fascinating, but kind of impenetrable. I still remember when the Inquirer went through a brief period of republishing the Hal Foster strips – that sense of startling realization, that this was the genuine article, really stuck with me.

A little later I got into superhero comics. Every dollar I could ever scrape together between the ages of 8-15 was spent on Marvel comics. Spider-Man was my favorite. I also loved a lot of the newer characters like Cloak and Dagger, Nova, Ghost Rider. I worshiped Stan Lee, less for his comic stories than for those goofy Stan's Soapbox columns where he would alliterate and enthuse and hype everything. His hype worked on me – I was totally committed to Marvel, and to Stan in particular. In the third grade I did a book report about his ghost-written memoir. I was pretty crushed to find out some of the scummier aspects of his dealings.

I liked a lot of the smoother, more old-fashioned and romantic styles. I've grown to be a giant Jack Kirby fan but his stuff was too wild and sharp for me when I was a kid. I knew even then how incredible it was – but I think maybe I wasn't ready for it. I liked John Buscema a lot. John Romita Sr. was my favorite Spider-Man artist. The way Ditko drew Peter Parker freaked me out, but I loved his Doctor Strange. Jim Starlin cosmic stuff blew my mind. Stuffy taste for an '80s kid, I guess.

My friends were getting into McFarlane and Liefeld and the whole Image thing, which I hated. The Image guys were too harsh and adult for me. Stuff like Spawn was really off-putting. I hated guns and giant muscles and cross-hatching. My Marvel universe was this clean, bright world full of vivid, deeply human characters. When the grim, angry stuff started to take over, beginning with my beloved X-Men and bleeding into everything else, my interest in superhero comics waned.

When I was in high school I started hanging out at a local comic shop and began to realize there were all kinds of different comics in the world. I thought it was just newspaper strips, superheroes, and Groo. Dave Sim's Cerebus was one of the first things to demonstrate to me the mind-blowing potential of the comics medium. It was like: oh, you can make a 9,000 page Tolstoy-esque epic about a hermaphroditic aardvark who becomes Pope? And it can be deep and thoughtful and gross and weird and satiric and brilliant and stupid all at the same time? I was realizing that you're literally allowed to do whatever you want.

Peter Bagge's Hate comics cracked me up and spoke to me very directly. Through Bagge I found Robert Crumb, and Harvey Pekar, and realized you can make comics about regular life, without radioactivity or traditional punchlines. Neil Gaiman's Sandman really crawled inside my imagination and set up shop. I read every issue over and over, like I was trying to crack a code.

Comics at this point started to mean something different for me – they'd always been this beloved form of entertainment and escapism as well as these glorious fetish objects, but as I started to read weirder and weirder stuff they began to represent freedom as much as they did pleasure. A lot of these comics from Vertigo and Fantagraphics had sex and violence and mind-bending artwork and gigantic literary ambitions and worlds within worlds of their own. They represented everything that seemed wild and unfettered and hopeful about art and stories and life. I wanted to see how weird they could get. Which, years later, led me to turn-of-the-century newspaper comics, which is really where the weird got started.

I wish that list weren't all men. A huge amount of my favorite cartoonists now, and many of the cartoonists whose work I'm most excited to publish and champion, are women. Andrea Tsurumi and Lisk Feng in particular I think are two of the most important and vital voices of the younger generation. But if I'm being honest about my formative influence – up until a certain point it's a sausage fest. Which doesn't speak well of the comic industry – or, I guess, of me.

JO: It was all pretty haphazard. Chris and I met working at the Video Library, which was an old West Philly institution, a fantastic movie-rental palace that was sadly past its expiration date. With the video rental business dying, they were making sort of a half-hearted attempt to expand into the comics market.

We hit it off right away. Chris' love of comics is maybe even deeper and more insane than mine is. I had made forays into trying to create comics of my own, with a couple of webcomics I'd written for different artists and a little stack of scripts and pitches I was showing to people, but Chris had spent a decade on a crusade to make a name for himself as a comics writer. He'd been published in a couple of anthologies and had worked with amazing people like James Jean, Farel Dalrymple, Jae Lee, Art Adams and Nate Powell. Once we got to talking it seemed like a foregone conclusion that we would make comics together.

Andrew was a customer at the shop who quickly became a friend. Among many other plans that were floating around, Chris had this great idea for an anthology of science-fiction fairy tales. The world's oldest, most beloved stories spun off into distant futures. We called it Once Upon a Time Machine.

Soon after we began working on Once Upon a Time Machine, we realized that where most people have a brain, Andrew has some kind of hydraulic-powered editorial supercomputer. Andrew works with the delicacy and thoughtfulness of a field paleontologist, gently, persistently revealing the buried skeleton in the structure of your story. He can find beauty and clarity in your work that you didn't know was there. His attention to detail and innate sense of narrative structure are second to no one in this business. It was pretty clear that he should be the editor of this anthology – and eventually the Editor-in-Chief of what became Locust Moon Press. Which also helped us out, because Chris and I were suddenly busy opening a comic shop.

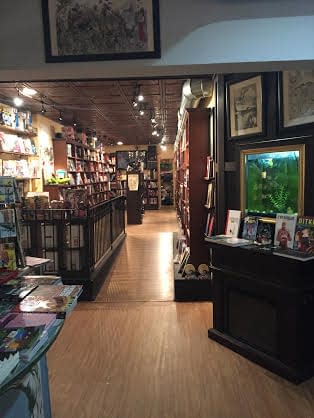

In 2010 the Video Library closed its doors, and we somehow scraped together enough cash to rent out its location. It was a pretty shitty spot – an old, out-of-the-way, hastily divided warehouse space that we shared with a gaming store. We were cocky, and didn't realize we had no idea what we were doing. Our first few years were kind of a constantly unfolding disaster, but we managed to hang in there. I'm still not quite sure how we stayed in business. We're stubborn people.

In 2012 we moved to our new and improved location on 40th street. I think our customers and collaborators have stayed loyal to us because, for all our faults and mistakes, our hearts are consistently in the right place. It's a privilege to be able to introduce people to new books, to guide them to these amazing pieces of art and storytelling. We care deeply about comics as a medium. We have faith in the importance and power of artistic community. We believe that people are here to lift each other up. That's what Locust Moon represents, at its best.

So hey, we're still here. It's a tough beat, running a comic shop. Especially one that caters more to the eclectic, independent side of the industry than the sales-tactic-driven superhero franchise market. But it's enabled us to build this little temple to the medium we love. It gives us a place to stand, where our kindred spirits can find us. We keep finding more and more. Cartooning is hard, lonely work. Its practitioners need a place to come together, and we do the best we can – as both publishers and shop proprietors – to give them a home and a family.

NF: In Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream, you, Chris, Andrew, and a host of extraordinary cartoonists not only managed to capture the awe and terror and wonder of McCay's original – you also created a monumental work of art, an anthology of imagination unbound. Looking back on your Nemo journey, from the idea's inception to the book's publication, what has this project meant to you?

JO: It doesn't matter how many times I re-read McCay's strips – they always seem so strange and awe-inspiring and otherworldly and glorious. They just bubble with some kind of joyous, mysterious magic. And the fact that we were even able to brush up against that magic – to become in some small way keepers of his legacy, custodians of this great map charting his influence – is something for which I'll be eternally, overflowingly grateful.

I've talked and written so much about this book in so many places, I won't get too deep here. Suffice to say that working on this project – being, with Chris and Andrew, the midwives who helped deliver this weird, beautiful, gigantic baby into the world has been the greatest honor, privilege and pleasure of my life. The deep love and respect that McCay commands in the comics world allowed us to somehow catch lightning in a bottle. This little nobody company from Philadelphia published a book featuring Paul Pope, Bill Sienkiewicz, Mike Allred, Craig Thompson, Yuko Shimizu, Dean Haspiel, David Mack, John Cassaday, et cetera et f*cking cetera. That's all thanks to the century-long coattails that we grabbed hold of, and are still clinging to for dear life.

It just occurs to me – out of that list I just gave of people who blew my mind in high school, a huge majority of them participated in this project. Peter Bagge was one of the first people to submit a strip. Gerhard, who did the gorgeous Cerebus backgrounds, drew the transcendent title page, which many people mistake for a McCay original. A whole host of Sandman artists contributed – Kelly Jones, Jill Thompson, J.H. Williams III, P. Craig Russell. Probably others I'm forgetting. It seems like some insane dream I'm having, where I somehow crawled inside the books I loved. Sometimes I think I might suddenly wake up and find that I'm still a teenager who got too high one night and passed out with a stack of comics on his chest.

Through very little fault of our own, this book turned into a catalogue of modern comics geniuses, and a kind of a state-of-the-medium address. It shows the huge and limitless power of comics. And it's all done out of love and admiration – these artists hear a call from a century ago, and respond with love and wonder and ambition and a little bit of fear. It speaks to McCay's seismic influence, and the continuing resilience and power of his work.

Still – the book will always be incomplete, because we didn't get Bill Watterson.

NF: Locust Moon releases a quarterly comic book anthology, Quarter Moon, of which you're the publisher. Quarter Moon's stories range from the mind-bending to the heartfelt, and feature an array of accomplished comic creators – including Mike Sgier, Andrea Tsurumi, Dave Proch, Rob Woods, Farel Dalrymple, Alexandra Beguez, and J. G. Jones. Talk a bit about this anthology series and your experience publishing it.

JO: Quarter Moon was born out of the frustration of all these long term projects we were working on. Little Nemo, the sequel to Once Upon a Time Machine, and Rob Woods' 36 Lessons in Self Destruction collection each had gestation times measured in years, and I really wanted do something that was more immediate and fun and light on its feet. And something that would keep us on a constant production schedule, making mistakes, learning and changing.

It was also born out of the sad fact that very few magazines like this still exist, and they're such a wonderful format in which to discover new comics and great cartoonists. Anthologies like Mome, Raw, Weirdo, Blab, Kramers, etc., were an enormous part of my comics education and I used to devour them all, until one by one they all disappeared. Even their more mainstream cousins, like Popgun and Flight have folded. There are a few noble holdouts and fellow upstarts – Mineshaft magazine has a hot new issue on the way. I really like what Alex Rothman has done with the first couple issues of Inkbrick and I hope he continues to put that out. Paper Cutter is reliably terrific. But really high quality periodical anthologies are few and far between these days, and I want us to do our part to remedy that.

The cover of the newest issue was drawn by Denis Kitchen, which is a huge honor — both because Denis is living legend and one of the best cartoonists out there, and because it sort of aligns us with the great underground mags of the '70s, many of which Denis published and contributed to. I like the idea that our magazine is a little bit of an anachronistic throwback – a stubborn little scrap of a once-great lineage of weird comix anthologies.

For whatever reason this format just doesn't play so well in the marketplace. I don't understand that at all – where else can you discover a dozen bizarre and original cartooning voices for a few bucks? People who don't buy these things – not Quarter Moon specifically but the many dearly departed books in this format – are depriving themselves and depriving the comic industry of this tremendous outlet for a multiplicity of singular cartoonist's unique voices. It's a format that gives people a chance to play and experiment, and this medium is lesser without it.

We give each issue a theme. Like cats, or food, or sex, or revenge. It's fun to see how these terrific storytellers process the theme and distort it through their own vision. Book designer and cartooning mastermind James Comey is probably my most frequent comics collaborator and one of my best pals in the world, and I get to work very closely with him on the layout and design. Andrew provides editorial guidance, pulls his hair out fixing all our fuck-ups, and makes sure everything looks great. Putting out Quarter Moon is one of the most fun things I get to do. I hope and plan to keep doing it forever.

I wish I could convince more people to buy it, though.

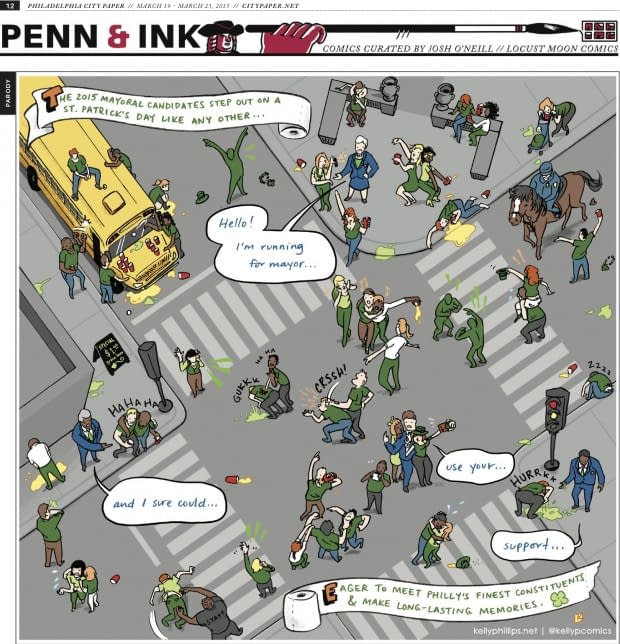

NF: With the caliber of talent involved, it definitely deserves a wider readership. Another ongoing project you're working on is City Paper's brand new weekly comic strip, which you'll be curating. Congratulations! What can we expect from your new ongoing newspaper comic?

JO: In some ways, it seems like an extension of the magical momentum of the Little Nemo book. I met Lillian Swanson, the editor of the City Paper, through a feature that they did on Locust Moon. They used Peter and Maria Hoey's Nemo strip – with the text rejiggered to tease the stories inside – as their cover image. Everybody loved that cover, and Lil and I got to talking about local comics, and the sad history of newspaper strips, and what emerged is this new adventure.

The Philadelphia City Paper is now the only newspaper in the country (and maybe the world) running a full-page, full-color comic strip in every issue. We're going to use this amazing outlet to showcase the incredible variety of local talent (Box Brown, Daryl Seitchik, Mike Sgier, Kelly Phillips, Dave Proch, Jeffro Kilpatrick and many more), alongside out-of-town ringers like Dean Haspiel, Pete Bagge, Ronald Wimberly, and Andrea Tsurumi. All the comics will be about the spectacularly weird, fucked-up, soulful wonder of Philadelphia – our culture, our politics, our history, our people, our music and art and sadness and joy and hope.

It's a continuation of one part of the work we were doing with the McCay tribute – turning back the clock to a time when it wasn't strange for cartoonists to have this glorious expanse of a newspaper page all to themselves. Alt weeklies and newspapers in general are in a sickly state right now, and newspaper comic strips are on life support. This experiment with the City Paper is a beautiful anachronism. I'm excited to see how far we can drag the past, kicking and screaming, into the future.

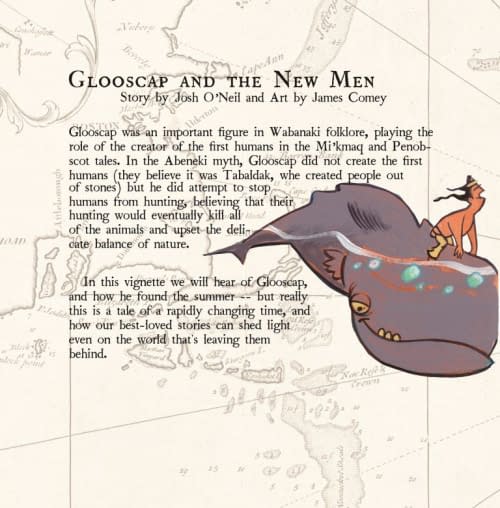

NF: You and artist James Comey contributed to Fulcrum's Colonial Comics, an eclectic collection of historical tales set in colonial New England, with your story "Glooscap and the New Men." Like your fairy tale "Bombus and Vespula" in Once Upon a Time Machine, "Glosscap" is a story about clashing perspectives and competing histories. Who is Glooscap and how does he differ from the "New Men"?

JO: Glooscap is a hero character from Wabanaki native American mythology. He's a sort of demigod type. He's virtuous and kind and can speak to animals. The story that Jimmy and I made for Colonial Comics is about an Algonquian father and son watching a European whaling expedition near Nantucket Bay. They don't know who these white people are or where they came from, and they don't have any context for the nautical technology they're seeing. As [they're] watching the new men kill this whale, they tell each other a myth about Glooscap, and question the fate of a minor whale character in his story.

One of the things that interests me most as a writer, and also just as a person, is the concept of conflicting narratives. I look at stories as living things that compete for survival and primacy, just like any other organism. Whoever owns mythology owns culture – a king is just a guy who's convinced everybody to buy into the idea that he's the protagonist of history. That's how we can care so much about celebrities and icons and step over bums in the street. The corollary of hero worship is disdain for regular people. We don't worry much about the minor characters.

Things like the American belief in Manifest Destiny arise from the assumption that this is our story. We're the protagonists. If you unconflictedly believe that you're the most important player in a historical narrative, you can commit a demonic, inconceivable genocide as casually as you'd brush ants off a picnic table. I think that storytelling can be this tremendous engine of empathy and understanding, this chance to feel the beating heart of another person – but the protagonist-driven structure of Western narrative can be a really dangerous self-justifying trap.

So those two comics – "Bombus and Vespula" and "Glooscap and the New Men" – are both aimed at exploding the protagonist myth. The books that they they're contained in, Colonial Comics and Once Upon a Time Machine, are intended for young readers, and I guess my goal was to try to give some kind of useful moral instruction, without being finger-waggy or didactic. I wanted to make these little parables that point to the fact that the world is much larger and richer and more complex than we can ever conceive, and it's easy to get stuck in your own little blinkered narrative. Your story is not reality – it's just your story. Everybody has one, and theirs are as meaningful as yours. It's such a simple truth, but you can spend your whole life trying to learn it.

By the way – how good does Jimmy's art look on the Glooscap story? Crisp gestural cartooning with this almost childlike, incredibly evocative crayon coloring style. And he manages to inject all this charm and humor into my very somber writing. I'm so happy we got to do that comic together.

NF: Jimmy's a gem! Finally, what other projects do you have down the pipeline that you'd like to talk about?

JO: So much good stuff to come. Andrew's been spearheading the sequel to Once Upon a Time Machine, and it's getting close to finished. Sci-fi adaptations of Greek mythology. I just finished collaborating with Toby Cypress on a version of Orpheus and Eurydice, and I just can't believe how beautifully it turned out. Toby's one of the most visionary artists working in comics. I'm also working with my good friend Charlie Fetherolf on an adaptation of the slaying of the suitors at the end of The Odyssey. Charlie's comics are such transcendent music, and I've always wanted to collaborate with him on something… his designs for this far-out revenge fantasy we plotted together are looking like some pretty serious next-level shit. Between contributions from Paul Pope, Ron Wimberly, Andrea Tsurumi, Aaron Conley, J.G. Jones, Greg Benton and like a thousand other people that book is going to be too much rock and roll to contain between two covers.

We're about to partner with Francoise Mouly's Toon Books imprint to release Little Nemo's Big New Dreams, an abridged, smaller-format partial edition of the Little Nemo tribute aimed at schools and libraries. We just got our first advance copy and we couldn't be more pleased or excited. I never would have thought that a little hardcover like that could do such beautiful justice to these giant strips. I'm excited to have a chance to get some of this amazing work into the hands of kids and inflict crucial weirdness on their vulnerable young minds.

We're also putting together a collection of the very earliest work of Will Eisner – two strips called Harry Karry and Uncle Otto that predate anything else he ever published. These things were dug out of a trove of printing plates by a collector in New Jersey, and I think that they're of giant historical significance – you can really see the roots of The Spirit. You can see Will Eisner becoming Will Eisner before your very eyes. It's a real honor to be among the people preserving and expanding Eisner's legacy.

Quarter Moon six is looking like a quantum leap forward, with stories and illustrations by Farel Dalrymple, Paul Pope, Bill Sienkiewicz, Dean Haspiel, Matt Huynh, Mike Sgier, Lisk Feng and lots more. Plus it's about cats, and everybody loves cats. I'm thinking that this is the issue to really put Quarter Moon on the map. It'll be out in early July. Ben Kahn and Bruno Hidalgo are in the midst of an extremely successful Kickstarter for their book Shaman, and we're planning to put that out this year. We're working on a collection of JG Jones' astonishing sketchbook material. Then another dozen or so tantalizingly amazing projects in various stages of I-can't-announce-that-yet.

Jesus. Listing all that stuff is stressing me out about how much time I'm spending on this interview. So much work to be done.

That's it for now. There are comics to be made. Thanks Nikolai.

NF: Thank you Josh!

Josh O'Neill is a Philadelphia-based comic book publisher, editor, writer, and co-founder of Locust Moon. Follow Locust Moon on Twitter @LOCUSTMOON and visit their website here.

Nikolai Fomich is a Philadelphia-based writer and teacher. Follow him on Twitter @brokenquiver