Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: chris claremont, cobra, collectibles, Comics, entertainment, g.i. joe, harvey kurtzman, joe kubert, Kenner, larry hama, michael golden, spider-man

Four Color Roots Part 3: 1991 Was The Year For G.I.Joe, The Rocketeer, And Spider-Man

By Christopher Smith

In this, the third installment of our ongoing column series, Christopher Smith takes us on a tour through his own back pages as a comics fan, going down unexpected dark alleys and digressions. Focusing only on the comics and pop-cultural touchstones he experienced at the time, he reconsiders their (at times unlikely) influence and impact from a modern-day context, and his own journey through the four-color and geek culture worlds that's apropos of so many comics fans and pros of the same generation.

Last time, he explored the trends towards dark and gritty superheroes, in both writing and artwork, that reached him as a somewhat bewildered child. Intrigued to read more, he had yet to really delve into comics fandom, or visit a specialty store. It was now time for our young hero to dive in. With apologies to Harvey Pekar: Here's our boy now, checking out the spinner rack at a mall Waldenbooks…

Zappa: Well, here's my plan: We have an outfit called United Mutations which is basically a pen pal club. We have about 5,000 letters so far. By 1972 these kids who are 17 and 18 now are going to be ready to vote. Some of the kids are amazing, they are so perceptive and so into their own special local social scene.

Scott: How do you find them?

Zappa: I don't find them, they just write to us. Of course, it helps when we run an ad in "Marvel Comics."

– Frank Zappa, interview with Stuart J. Scott, 1968

The old adage in comics, which I've heard attributed to both Stan Lee and Jim Shooter—one of many well-documented sources of frustration for those who toiled away under his reign in the 1980s—is that "every issue is someone's first." G.I. Joe #107, published in December of 1990, written by Larry Hama and with art by Lee Weeks, wasn't my first issue, but it was the first one that worked its peculiar magic on me, serving as an introduction to what this medium of ongoing serialized storytelling could do. Secret Wars wasn't something I was old enough to comprehend as a narrative; Frank Miller's Batman was so dark as to be utterly incomprehensible yet somehow still terrifying, not unlike premature brushes with adult content via cable TV and its scrambler boxes. But G.I. Joe traded in the familiarity that I had with the subject matter as a fan of the eighties cartoon (itself quite smart and subversive, if Hama at least one time went on record as saying he hadn't watched it).

It squared the circle of television fandom into comics; there's a reason why media tie-ins sell so well, to children, avid fans of the properties, and entry-level readers alike. Who wouldn't want more of that thing you love, especially since the cartoon had changed production teams (the omnipresent DiC were now at the helm) and into something, at this time, that was recognizable even to my ten-year-old brain as watery gruel compared to the heights of the Sunbow series. I didn't even really know why I still watched it, really; I felt a little bit of pressure that I was too old for this mode of storytelling. After all, I distinctly remember getting ridiculed for wearing a Snake-Eyes fanny pack to a class trip to colonial Williamsburg, yet I belonged when playing Konami's coin-op Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles arcade game in our hotel. Maybe it was just because my dad was supplying a few quarters to everyone could keep their game going, but even now, there's an almost subconscious division that certain properties were cool, and others weren't.

Something about this issue of G.I. Joe, though, was cool, to me. As a licensed and code-approved title, it didn't descend into blood-and-guts nihilism, but nor was it a squeaky-clean and dull comic like I remember the M.A.S.K. mini-comics that I remember coming with the Kenner toys (apologies if it turns out these were ghost-written by Justin Green with art by R. Crumb or something; I haven't looked at them lately. I do remember that one character's exclamation of Mon Dieu! was enough to get an issue taken away from me, when a parent found out what that meant). It dropped me into the midst of a Byzantine web of continuity, like all superhero titles, and promised to reveal what was behind Snake Eyes' mask (this had happened, in fact, sometime recently, judging by the letters pages – I had a burning need to find this issue at once), and Cobra Commander's hood.

In short, I was hooked. But it was a bit of an uphill battle. True, comics weren't cheap (the cover price was $1.00), I was parentally discouraged from reading them, as there was far more age-appropriate material available, you know, like all those books I wasn't really permitted to read that dealt with D&D-inspired fantasy worlds, or young-adult themes (divorce, substance abuse, et al. But I wasn't that interested in them, really; I was, however, discouraged). Nevertheless, I was hooked. At one time (and certainly to me as recently as the mid-2000's), this series seemed like an obscure gem. Now, much has been written on this site and elsewhere about the riches of the original Marvel Joe run: Hama wrote most of the 155-issue run, he balanced as many plot threads (and resolved them satisfactorily, under threat of cancellation) as Chris Claremont in his prime, and certain special editions like the annuals showcased the superb artwork of Michael Golden. It's almost mandatory at this point for an online comics site to showcase a thinkpiece about the classic issue #21, "Silent Interlude," both written and penciled by Hama, which many creators clearly read and namechecked as an influence. Arashikage Clan hexagram tattoos are a lot more common than you'd think, among pro wrestlers, gas station attendants, and singers of hardcore punk bands alike.

However, issue #109 truly brought something new to the run and my mindset at the time; a pointed political commentary on the contemporaneous Gulf War, it featured the lasting deaths of several members of the team, including a few of my favorites (Quick Kick! Noooo!). Hama had gotten through to his young readers, getting them to understand the sudden inhumanities and callous cruelties of war. That alone locates G.I. Joe in the company of the best work of Joe Kubert and Harvey Kurtzman.

If the house style of G.I. Joe and its narrative structure served as a synecdoche of the Marvel Universe in general, there was a secondary aspect that can't be overlooked: letters pages and Bullpen Bulletins. I absolutely ate these up as a kid starting to dream of working in comics someday, to the point that meeting a few of these personalities left me considerably starstruck as an adult. For instance, Renee Witterstaetter complimented my wife's Wizard of Oz totebag at Mid-Ohio Con a few years ago, while Michael Golden signed a Spider-Man print I bought.

I didn't tell either of them this, but they were celebrities in my world. I didn't go in much for sports, music, or even live-action TV much, at that age. Home Improvement was a dull ambient backdrop to the monklike process of poring over my Marvel Universe trading card sets; I like to think I'd have been somewhat unimpressed if Tim Allen showed up at my door. These profiles also dropped a series of breadcrumbs on the path to my cultural discovery: authors and artists in both comics and the literary field, quirky outsider musicians, and even historical facts got soaked up accidentally. Letter columns, too, offered a fan discourse, and a sense of belonging. I didn't know anyone who read G.I. Joe, and the clerk at one comic shop actively scowled at this little kid for buying it, and it alone, religiously every month, but there was something immersive about all the fan theories, exhortations of delight, and even the odd poem or bit of artwork that would get displayed.

And then there was the postcard. At more than one point, I wrote in, sharing some oddball theory about Snake Eyes and his yet-unstated connection to the Baroness and Cobra Commander, perhaps, or some clue Hama hinted at having been secreted away on the cover to 1984's issue #26 (more on that in a moment). Sure enough, I not only had a letter printed, but received a handwritten postcard from Hama in the mail. This was better than a No-Prize, and worked to build a connection that, to a child my age with relatively few friends, a child feeling increasingly alone in the education system, was huge. Someone, well, cared.

And I cared, too, as a quester, a collector. If you're reading this, you've either experienced or been lectured to by some geezer about the difficulty of finding things like comics or obscure records before the internet. One had, after all, to do their homework, and achieve the kind of total immersion that makes you obsessively motivated. It helped not having a lot distracting me from this pursuit, as I cared little for school at this point in my life, and my happiness and interest therein would be on a plateau, then a curvilinear decline until about 1995. I started hunting down the toys at garage sales; sometimes I could find them in decent shape.

Toys and back issues alike were sold by the first comic store I ever visited, a tiny basement affair whose name I can't remember, but was run by a man named Craig in Delaware. After descending some rickety steps, I spotted some Super Powers and G.I. Joe action figures in a glass case, marked up a tad, but not unaffordably so. Perhaps I had some birthday cash burning a hole in my pocket. I already owned a Destro figure, but I bought Storm Shadow and the Baroness that day; the former was my favorite character, complete with his tiny, frustrating-to-close backpack, bow, and swords. I admired him on a shelf, along with Green Arrow and Martian Manhunter, who I had yet to read in any comic-book appearances, but who appealed to me in some strange way. I can't quite explain how excited I was. Somehow, these were no longer toys to play with—that was kid stuff!—these were to collect. To admire.

I laid eyes on back issues, too, for the first time: sprawls of old comics, sometimes deteriorating, in yellowing bags and sealed since who knows when. There were UK editions of the somehow unsatisfying Action Force (what they renamed G.I. Joe abroad, relettered speech balloons and all), and of course, that #26, which I'd been looking for a good while at that point. The joys of the hunt, and its consummation, became known to me. I practiced the hunt at other local haunts, such as Between Books, which also sold fantasy books and had dusty model spaceships decorating its ceiling. The store sadly closed lost year, and served as a gathering post for many likeminded individuals in its span. Others, like the Comic Book Shop in Wilmington, opened that year, and are still thriving (it occupied the same location for decades, and just moved to a new one recently).

By that spring and summer, family vacations became an opportunity to visit other shops. The one I most fondly remember is Captain Blue Hen Comics in Lancaster, PA (it had a Newark, DE division, too, which still exists). Finding it on Google Maps produced a palpable sense of time travel and disbelief. Located below Souls for the Kingdom Fellowship Church, the store would often resonate, even shudder, with the sounds of stomps and handclaps during a lively gospel revival. They didn't have much in the way of toys, but stocked the occult-to-me twenty-sided die, current issues on display, and the hot speculator titles of the month, which were starting to become omnipresent.

They also had, at the base of their own rickety staircase, a Gauntlet arcade machine, which I remember wishing I could just sit on a barstool and play all day, exploring the endless dungeon crawl as Questor the Elf. There, too, were seemingly endless quarter—and possibly even dime—bins in some side rooms, which got a little sunlight let in. I found some odd titles here, like Marvel's 1984-1986 Amazing High Adventure anthology series, which focused on war and historical tales in a very niche pulp-revival mode. I was starting to learn and recognize some artists' work, and enjoyed this title a lot. Indeed, I mostly avoided buying superhero books, drawn towards the unshaven, tattered grit of Sgt. Rock and the deformed, compelling visage of Jonah Hex. I'd start to understand these titles a lot better in a few years.

Summer 1991 laid even more groundwork for an appreciation of recycled pulp fiction and serial tropes with Disney's The Rocketeer. Though I wouldn't learn of Dave Stevens' comic book until that same savvy friend who'd shown me Frank Miller's work pulled out a glossy edition of the title at a sleepover that took place around the time the movie came out, I was utterly engrossed by the compelling world of the title character, with its recognizably prewar air stunt shows, villains both menacing and debonair, and beautiful love interest patterned after Bettie Page (the appeal of which I would, again, definitely understand in a few years).

It looked fantastic and made me start to think that I was born in the wrong decade. It perhaps drew on the appeal of the previous year's Dick Tracy—both were heavily advertised and marketed to my age group, down to the level of Topps candy dispensers—but this film succeeded for me where that earlier predecessor failed. (Little wonder that its director's Captain America: The First Avenger is my favorite superhero film of recent years.) I even made a repeat trip to see it in the theater, something that wasn't often done in my household. I even brought both my parents the second time. I guess I didn't really have anyone else to share it with.

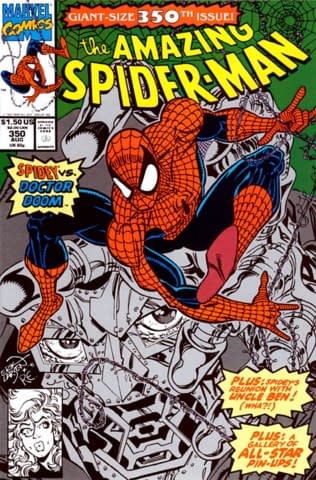

Meanwhile, August 1991's Amazing Spider-Man #350 delivered on another level I couldn't quite explain. I'm not entirely sure why I bought it, not necessarily being a huge fan of the character, whose cartoon, Pez dispenser, and Secret Wars action figure seemed more like the pop-culture flotsam of my childhood, and nothing I'd chosen on my own. Perhaps the speculator boom reeled me in, as it nearly did for Silver Surfer #50, with its embossed foil cover. Nevertheless, the comic's giant-sized action extravaganza certainly entertained me, but Erik Larsen's artwork held the true appeal. Something intricate, lively, and unique in his renderings of Spidey's kinetic action and even the interstices of Doctor Doom's face mask appealed to some intellectual/aesthetic plane in me in a way that McFarlane's didn't quite reach. You could study Larsen's pages, and find something new every time. Details, composition, and depth emerged. I know I reread this comic again and again on our summer car trip, and long thereafter. I also had by this time learned Spider-Man's origin, though it'd be a while until I read its full reprint.

Absorption in the Marvel Universe and its ongoing mythos, though, was in full effect. In July, Jim Starlin and George Perez's The Infinity Gauntlet achieved liftoff, and certainly captivated the attention of some of my classmates at the lunch table by September. Along with the grandiose heights of grotesquerie reached by Ren and Stimpy, or the transgressive racial and sexual humor of In Living Color or Married with Children, Thanos' omnipotent dismissals of the Marvel heroes were comprised a good percentage of the preteen equivalent of water cooler conversation. We couldn't possibly see how this storyline could resolve itself, but had to know.

Soon, I jumped onboard, and was able to fill in gaps in my continuity knowledge from those Universe trading cards, even if it'd be about two decades until I'd read the original Starlin comics that laid the groundwork for Thanos' return. But what struck me as a little surprising was that, suddenly, other kids my age were into comics. A lot of them were. Usually, some key issue would be passed around at school, and one with a spectacularly visceral or doomy feel, such as anything featuring the Punisher or Ghost Rider (himself the recipient of a gimmicky glow-in-the-dark cover). I have a particularly strong memory of peering over a classmate's shoulder at the grim, deeply unsettling Amazing Spider-Man #293, which boasted not only the black suit but Kraven triumphantly dancing atop his adversary's grave. Whatever we were studying in fifth grade English class that day, even Poe, paled in comparison.

That trend towards gimmicky covers, though, was taking off in earnest. Soon nearly every title had one. I tended to resist buying them, but I did pick up January 1992's Wolverine #50 featured a die-cut folder (a similar concept to G.I. Joe #26), slashed with its title character's trademark claws, but the story was great too, and was written by Larry Hama. Again, it was a rather weird jumping-on point, and an immersion into a whole separate superhero mythos, this one featuring a baroque mixture Philip-K.-Dick-esque manufactured memories and reality slippages. At some point, I reread it, and all my other titles, sick in bed. I was starting to see connecting threads, and I wanted more. Immersion into the comics landscape was complete. It took a while, but the roots took hold.

Next time, we'll look at the "boom period" of 1992, the Image exodus, and the artistic and storytelling trends it drove. Will our young protagonist emerge at year's end a fan, or exhausted? Animation, too, relatively neglected in this installment, will receive an infusion of fresh blood with Bruce Timm's take on the Dark Knight.

Christopher Smith teaches composition at Columbus State Community College and has spent about two thirds of his life being obsessed with comics, music, and the strange, somewhat overlooked corners of pop culture. He lives with his wife, son, and two devious cats.