Posted in: Batman, Comics, DC Comics | Tagged: architecture, baman 86, Batman, crime, gotham, james tynon IV, spoilers, tony s Daniel

LONG READ: James Tynion IV's Batman #86 to Solve Gotham's Crime Through Architecture (Spoilers)

Okay, 2250 words, settle in. But first a trip back almost two hundred years. In 1831, Lord Macaulay argued in the House of Commons in London that there was

"nothing is so ill-made… as the laws… Our bridges, our canals, our roads, our modes of communication, fill every stranger with wonder… Can there be a stronger contrast than that which exists between the beauty, the completeness, the speed, the precision with which every process is performed in our factories, and the awkwardness, the rudeness, the slowness, the uncertainty of the apparatus by which offences are punished and rights vindicated?"

Basically, architecture was better at dealing with problems than the law. So the issue has been talked about for a long time. And it keeps coming up. Almost a hundred and fifty years later in New York, 1973, architect and city planner Oscar Newman published Architectural Design for Crime Prevention, formulating his defensible space theory. He wrote,

Low- and medium-income housing developments in our Nation's inner cities face a problem so severe it has come to threaten their very existence. Victims of a peculiar mix of social and physical circumstance, housing projects have become those areas of our inner cities most susceptible to crime and vandalism. Crimes against persons and property are so commonplace, police are no longer able to view reports of simple burglary with serious concern. Vandalism is widespread and its impact is to further dishearten residents and to lead them to the abandonment of previously felt concern. The withering of funds for maintenance and repair ensure that the effects of vandalism will remain with us a long time, in many instances never to be redressed.

He stated that,

We are now certain that the physical construct of residential environments can elicit attitudes and behaviour on the part of residents which contribute in a major way toward insuring their security; that the form of buildings and their groupings enable inhabitants to undertake a significant policing function, natural to their daily routine and activities. These functions act as important constraints on antisocial behavior. We believe them to be a most effective form of target hardening not prone to the changing modus operandi of criminals and one which unmistakably make evidence to prospective criminals the high degree of probability of their apprehension.

And that,

It may be disconcerting for some to learn that the form of the physical environment has capacity for not only limiting activity but for evoking behavioral attitudes and responses from inhabitants. Where we are probably all familiar with the restrictive capacities of architecture when employed as a buffer against intrusion, both through the use of high walls and by the clustering of buildings to create fortlike configurations, the evidence we have been compiling over the past 2 years indicates a far more significant capacity: that by grouping dwelling units in a particular way, by delimiting paths of movement, by defining areas of activity and their juxtaposition with other areas, and by providing for visual surveillance, one can create in inhabitants and strangers-a clear understanding as to the function of a space and who are its intended users. This we have found will lead to the adoption by residents, regardless of income level, of extremely potent territorial attitudes and self-policing measures.

In 2001, former Solicitor General Neal K. Katyal – Professor of National Security Law at Georgetown University Law Center, wrote about using architecture as crime control. In a paper for Georgetown University Law Center, he argued that

"perhaps because crime is about breaking the law, the natural impulse has been to think about law enforcement as its solution but that he "urged reconsideration of this impulse… in light of advances in architecture that reduce the need to rely on traditional law enforcement" and concluded The changes to architecture can range from the most fundamental, involving questions of how tall buildings should be and where they must be placed, to the most minute, such as whether door frames should face inward or outward. Some of the most promising solutions concern public lands, such as streets, parks, and public housing."

He gave an example of a young lawyer in a prominent Washington, D.C., law firm who told him

"you were supposed to take the (deserted) fire stairs if you were only going one floor but I always took the elevator (and annoyed people) because the fire stairs presented an obvious risk of rape. Just another aspect of the macho firm culture-besides locating the firm in an area where women could not walk safely at night…. I wasn't just completely paranoid, because the stairs meant that several thieves who entered the building stole laptops or wallets, and then had an easy escape …. Fear of rape is a serious problem for women in terms of travelling and even walking around at night, and architecture makes a huge difference."

And he laid out some basic principles.

First, architecture can make law enforcement more likely to succeed in its task of catching criminals. Public

areas can be made more visible, enabling witnesses and police to observe wrongdoing, and can be configured in ways that make escape more difficult. Second, architecture can modify the social norms of a community. Design can influence the attitudes and beliefs of individuals about a given neighborhood, draw into a community law-abiders with a vested interest in social order, and create conditions conducive to the development of trust among neighbors. Third, architecture can shape preferences away from crime, for example, by influencing the psychology of aggression. Fourth,design can make crime more expensive, thereby creating cost deterrence. When neighborhoods are planned in ways that make surveillance more likely, criminals will incur additional expenditures to carry out their crimes, and such expenditures can deter the criminal act…. Rent control may decrease crime because it will encourage rootedness.

In 1995, Los Angeles created an inter-agency "Design Out Crime" task force, led by representatives of the City Planning Department and Police Department, but including eight City agencies. The task force developed a set of "Design Out Crime" guidelines, adopted officially by the City Council, for distribution to developers, architects, urban planners and others involved in the design of building projects. The guidelines are also used by City agencies, such as the Housing Department, as criteria in evaluating projects worthy of City funding. They invested $25,000 in publishing 'Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design' guidelines and training staff in how to assist developers and built environment professionals design better environments that discourage crime. The programme aims to ensure all residents are safe, whether they live in luxury apartments or affordable housing.

The New York Times notes that New York's The Highline development also experiences lower than average crime and that in 2011, two years after opening,

The police, the city's Department of Parks and Recreation and the founders of the High Line all say there have been no reports of a major crime — assault, larceny, robbery, worse — since its opening.

The Green Man Lane estate, built in Ealing, London in the seventies was plagued with antisocial behaviour and drug-related crime. A 2007 study concluded it was plagued by serious problems that were either exacerbated or caused by the architecture, including fragmented street patterns and a lack of clear and safe routes through the estate, poor public spaces and dereliction. A new five-hectare Green Man Lane development in 2012 was intended to design-out crime, to make life difficult for street criminals and drug dealers. Including replacing multiple escape routes, aerial walkways and open access undercrofts with more traditional streets and pavements, natural surveillance from passing traffic, pedestrians and nearby homes, as well as CCTV, and overlooked streets with traditional front doors. Rear gardens no longer accessible from car parks or other public spaces, instead backing on to adjacent gardens or the secure community gardens, car parking moved to streets, and houses and ground floor maisonettes given front gardens with railings to create defensible space and deter nuisance attacks, with pathways through these areas designed to be more obvious and signposted thoroughfares. These kinds of redesigned living spaces have been shown to reduce burglaries by half, car-related crime by a quarter and a greater feeling of safety.

In 2015, Adithya Prasad, architect and Senior Workplace Consultant wrote similarly about Indian cities, saying,

One very crucial underlying factor which can either exacerbate or dampen crime is the architecture, design and urban quality of cities, which is most often overlooked. If one carefully looks through a number of urban crimes over the years, it will be evident that a large number of such crimes are committed in abandoned sites, buildings and spaces which are neglected and isolated from the rest of the urban fabric. Elders who live in stand alone suburban houses, women who are alone at home in isolated neighborhoods far from urban activity are all increasingly targeted because of their isolation from other people in the region. Although there are a number of crimes which occur in highly populated areas (such as pick-pocketing and chain snatching) far more serious crimes can be averted to a large extent by careful urban and architectural planning.

A 2017 study has shown how projects like The 606 in Chicago, which includes an elevated greenway, can reduce crime in adjacent neighbourhoods.

"Rates of violent, property and disorderly crime all fell at a faster rate in neighborhoods along the 606 than in similar neighborhoods nearby," lead study author Brandon Harris said… "The decrease was largest in lower-income neighborhoods along the western part of the trail."

So why is all this being talked about on Bleeding Cool? Because now it is Batman's turn. Bleeding Cool has run a number of articles of late as more and more people have pointed out that Batman could be the problem not the solution to Gotham's crime wave, from The Patriot Act on Netflix, the UK Labour Party activist group Momentum and Alfred Pennyworth himself in The Batman's Grave.

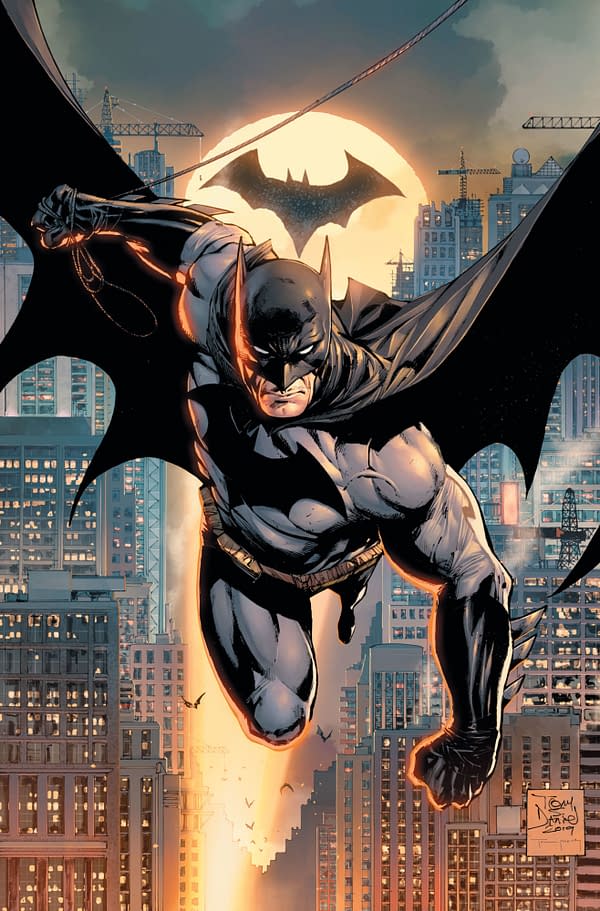

In the new Batman run by James Tynion IV and Tony S Daniel, Tynion has talked about creating a different looking Gotham.

That rebuilding should be part of the spirit of the city itself in 2020. There are strange metal spires and scaffolding jutting out into the air. There are spotlights all over the city, as construction continues 24 hours a day. The clangs of industrial jackhammers lend a new dark music to the city. Gotham feels like it's in the midst of a metamorphosis, change is in the air. There are giant cranes and spotlights everywhere, the way it all juts into the sky it feels like a claustrophobic nightmare… You can't tell where one building stops and another begins. A kind of eerie, industrial fog drifts through the city at all hours. The skies of Gotham are a dark, eerie red. It always feels like night-time. The city itself should be juxtapositions of strange Art-Deco insanity by way of Anton Furst and Tim Burton, and sleek modern towers that somehow look MORE frightening. Strange high tech skyscraper cathedrals, complete with sleek modern gargoyles.

And it seems that this won't be a background choice, the comic will see Bruce Wayne joining the bandwagon of using architecture to solve crime rather than just beating up muggers in back alleyways. Why have those alleyways in the first place? Given that's how his parents died, it now seems strange that it's taken him this long to get round to it.

The first of Tynion's Batman stories, Their Dark Designs, drawn by the great architect himself, Tony S Daniel, inked by Danny Miki, coloured by Tomei Morey and lettered by Clayton Cowles, will be published on January 8th by DC Comics, and going to FOC this weekend. And it opens with Batman thinking to himself about the designs he had been doodling, making for how Gotham could look, how buildings could be redesigned to prevent crime, to be a city that doesn't need Batman and how Alfred Pennyworth, before his death at the hands of Bane, would challenge him to stop being Batman and be an architect, solving Gotham's crimes that way. And now, after his death, having Wayne Enterprises step up and start rebuilding Gotham in Batman's image. A new Wayne Campus. A way to sidestep Gotham City planning regulations through political corruption. And the Wayne Rebuild Committee overseeing it all. But of course, not everyone is on board with Wayne's plans, and there are significant groups with their own competing plans. Maybe get rid of all those alleyways behind cinemas for a start? But as Tynion also says,

It's the grime and grit of the 1970s and 80s in a world where the city never got cleaned up, but kept growing. Now it needs to become something new… But the eerie sense needs to be that it might become something even more horrifying than before. We're creating a present day dystopia that will serve as the bridge to what's next.

Sorry, Lord Macaulay…

BATMAN #86

(W) James TynionIV (A) Danny Miki (A/CA) Tony S. Daniel

It's a new day in Gotham City, but not the same old Batman. With Bane vanquished and one of his longtime allies gone, Batman has to start picking up the pieces and stepping up his game. Batman has a new plan for Gotham City, but he's not the only one. Deathstroke has returned as well, under a mysterious new contract that could change everything.

Beginning a whole new chapter in the life of the Dark Knight, the epic art team of Tony S. Daniel and Danny Miki are joined by new series writer James Tynion IV!In Shops: Jan 08, 2020

Final Orders Due: Dec 09, 2019

SRP: $3.99