Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: animal man, Antarctic Press, booster gold, brian azzarello, Brian Keene, City of the Dead, Comics, dan didio, dan jurgens, dc comics, dead of night, doom patrol, entertainment, future's end, Greg Ricka, horror, jeff lemire, keith giffen, Liz Gehrlein, Marvel Comics, novels, science fiction, The Last Zombie, The Rising

Talking With Horror Master Brian Keene About A Life In Dark Fiction And Why He Isn't Writing Futures End, Animal Man, Or Booster Gold

By Hilton Collins

Brian Keene is a prolific writer who's written more than 40 books, mostly in the horror, fantasy, and science fiction genres, but his fertile imagination has planted seeds in other media. He's penned comic books for various publishers, including Marvel and DC, but his 25-issue series The Last Zombie for Antarctic Press symbolizes his legacy as a storyteller. The series is an intense tale about humanity's fate post-zombie apocalypse and exemplifies Keene's taste for darker, action-oriented tales.

Keene's comfort with action is probably why he's had no problem crossing over into comic books, since the world of superheroes is famous for fantastical, larger-than-life fight scenes and adventures. Keene's comic book action, however, often comes with a horrific or violent bent. It's no wonder that the comic book characters he's written include the Doom Patrol, DC's outcast superheroes who are often portrayed as monstrous outsiders, and a story in the DCU Halloween Special, an anthology featuring stories about the publisher's biggest characters during the scariest night of the year. Keene's an expert at delivering dark fiction with tough protagonists who know how to fight, whether it's with swords, automatic weapons, superpowers, or their own hands and feet.

Bleeding Cool interviewed him about his impressive career. Keene had interesting news about why he isn't part of the creative team for DC's current Futures End weekly series and how he almost wrote Animal Man and Booster Gold projects.

Hilton Collins: You've written Doom Patrol #16 and DCU Halloween Special in the past, and you were originally to be part of Futures End. How did you form your professional relationship with DC?

Brian Keene: Liz Gehrlein and Keith Giffen, who were editing and writing Doom Patrol at the time, respectively, asked me if I'd like to guest-write an issue. I've been a fan of the team since discovering them as a kid in the late-70s, and I'd have killed to collaborate with Keith on something, so it was an easy "Yes" for me. That led to Janelle Asselin asking me to do a story for the Halloween special, and to Keith and I co-writing a Masters of the Universe one-shot. In-between those last two, I'd met with Dan DiDio and Jim Lee for lunch, and that seemed to go well, so I figured it would just be a matter of time before I got to write something more than fill-ins. And soon enough, I was asked to be part of the original Futures End team—when it was still Keith, Dan Jurgens, Greg Rucka, Jeff Lemire, and myself. Obviously, that line-up changed a bit prior to publication.

BK: Well, like I said earlier, Futures End would have been my first ongoing gig for DC. Starting out, they brought all of us on the writing team into New York City and put us up in a hotel for a week. Each day, we met with the editorial and brainstormed ideas for the weekly series. The problem was, editorial's mandates kept changing. Originally, they wanted us to do something based on the Judeo-Christian Rapture, where a large part of the DC Universe's populace would simply disappear. So, we'd brainstorm based on that directive. But the next day (and sometimes several times per day) they'd change their mind and want something completely different.

It's very hard to be creative in such an environment, but I was honored to be part of such an amazing team of writers, and pleased to be working with Keith and Greg, both of whom I'd been friends with for years. Also, like many longtime readers, I'd found myself dissatisfied and underwhelmed with parts of the New 52 and was excited at the prospect of helping to shape and steer it to what it had the potential to be. In addition to the weekly book, I was asked to pitch several other projects, one of which was Animal Man. Jeff Lemire and I sat down, and he filled me in on where the character would be and what he had in store for the end of his run, and I came up with eight issues that would have picked up where he left off. Four of them were a serialized story. The other four were one-and-done single issues. Editorial liked them. I was asked to pitch other stuff, too — Booster Gold, Ragman, Vigilante, and a few others. Of these, I was told Animal Man was a go, and several others "looked promising."

Unfortunately, none of them ever happened. Two months into the weekly project—two months, it should be noted, in which we were still trying to keep up with the changes in editorial mandates and were now required to brainstorm by phone every week—Greg had to leave the project due to other commitments. Brian Azzarello was brought on to replace him, and as a result, we were all brought back to New York again. While there, I learned that the original contractual terms I had agreed to had changed. And thus, I elected to follow Greg and leave the project as well. I don't hold anybody at fault. Business is business. I don't regret that decision and have been assured by many comic professionals whom I respect that it was the right decision. Unfortunately, it meant that all of my other pitches died, as well.

HC: Are you someone they have on-call to write for them when they need it, or does the relationship work differently?

BK: No, I'm strictly freelance. And in truth, they haven't [been] called since Futures End, and I don't expect them to anytime soon. But that's okay. It's not like I'm somebody just starting out, desperate to break into comics. I have the luxury of writing other things. There's an economic safety in that. I've got forty plus books to my credit. Comics are a nice side-project, but that's all they are. My primary bread and butter—the way I feed my kids and keep the utilities turned on—comes from novels. I've been reading comics since I was six-years-old. I'm 46 now, and one thing I know for sure is that I enjoy reading them much more than I enjoy writing them.

BK: I was doing a signing at BEA in New York, a big trade show for the book industry. Ryan Penagos from Marvel came over to my table and asked me to sign some books for him, and we got to talking, and he knew I was a Marvelite since back in the days of Steve Gerber on The Defenders. He put me in touch with editorial, and I pitched a few things, and the one that stuck was that MAX iteration of Devil-Slayer.

HC: How does writing for comic books compare to writing novels and short stories?

BK: They are very different animals, in several ways. First of all, comics aren't a solo act. I mean, yes, the writer does the writing, but comics are a visual medium, so the artist is every bit as much a part of the storytelling experience as the writer is. And being a visual medium, you have to think visually. With a novel, the reader uses their own imagination to envision the action, facial expressions, etc. In comics, it's your job, and the job of the artist, to depict those for the reader. With novels, or even novellas, a writer has room to stretch. An average novel these days is about 90,000 words long. You can take your time developing characters, setting, mood, atmosphere, [and] motivations.

In comics, you've got 22 pages to do the exact same thing. It's difficult trying to compress all that down. You want to develop characters and situations the audience will give a shit about and feel invested in and entertained by, so it's not like you can spend twenty pages having a bunch of superheroes sitting around talking over corn flakes about their motivations. It's a balancing act. In many ways, writing a comic script is like writing a screenplay. You're describing things for the artist or the director. With a novel, those two quantities are removed, and you're describing things directly to the reader. And then there are short stories, which are, in my opinion, the most difficult of all to write, and have some of the same challenges as comics do, as far as room for development.

HC: Can you tease any other upcoming comics you've got coming out from the Big Two?

BK: Nothing from either of the Big Two, at least not for the foreseeable future, but there's some stuff on the horizon from other comic companies. Unfortunately, nothing I'm allowed to talk about yet.

BK: Well, The Last Zombie differed from all of my other zombie stuff in that all 25 issues took place after the zombie apocalypse was over. It's set in a time when all of the walking dead have rotted away into nothing and focuses on what happens after that. What happens after the dead die again? How does humanity rebuild? Is there even anybody left to rebuild? And is the virus that started the epidemic still out there? What if it comes back? The only time you see zombies throughout the entire series is in flashbacks. Instead, the dangers and horror come from other antagonists—humans, wild animals, nuclear reactor meltdowns, disease, starvation, raging wildfires—all of the other things that would happen if 90 percent of the world's population died and then came back to eat people's faces off. I'm excited for that Alan Moore guest-stint on Crossed they announced recently. It sounds like a similar concept, but given that it's set in the continuity of Crossed, I can only imagine how utterly fucked humanity is going to be. That should be a lot of fun.

HC: You mentioned being friends with Keith Giffen, another writer whose work I like, thanks to what he did on Justice League International. How did you two become friends?

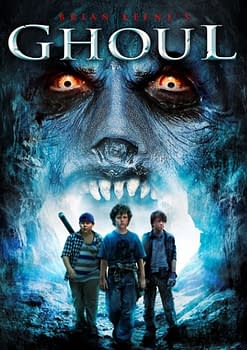

BK: I was a fan long before we ever became friends. I remember being aware of him as far back as Kamandi and The Defenders, but it was a small, eight-page comic he did for Steve Bissette's Taboo back in the late-80's that really made me a fan. To this day, it's one of the scariest, most-disturbing, and effective horror comics I've ever read. Anyway, I read a review he'd written about one of my books—I think it was Ghoul. I emailed him to say thanks and found out that he was a fan, and after I went total fanboy spaz on him and got all that out of my system, we became friends.

HC: Would you ever collaborate with him on another project?

BK: In a heartbeat. We've discussed it at-length. We're not short on ideas. It's just a matter of both of us finding the time. He's under contract with DC and I'm under several novel deadlines for the next six months or so. But eventually, I'm sure we will.

BK: Thanks, man. In truth, it was just a matter of writing a book that I'd want to read. That's how I approach everything I do. I try not to worry about audience expectations or genre traditions or what's been done before. I just focus on telling myself a story I'll enjoy, and hope that readers will enjoy it, too. As far as City—that was written over a decade ago, so it's hard to remember for sure. I think it took me six months to write it? Yeah, I think about six months. It's important to remember though, that I write for a living, meaning I don't have a day job to go to. This is my day job, and as a result, I can spend eight to ten hours a day working on a book, which is why I've managed to stay pretty prolific.

HC: Where did you come up with the idea to write that novelistic universe? Your first book in that universe was The Rising, correct? What inspired you to write that book?

BK: Like I said, it was just writing a novel I wanted to read. The Rising came out in 2003, around the same time as 28 Days Later and The Walking Dead. For many years before that, there hadn't been anything new, zombie-wise. No films, no novels, no comics. And then… BAM. Three of them, all inspired by what had come before, of course, but all three putting new spins, perspectives, or voices on those tropes. I wanted to read a zombie novel, so I wrote one. Judging by its success, a lot of other people wanted to read a zombie novel, too.

BK: It was for a long time, but it never made it out of development hell. But Dark Hollow is in-development, with Paul Campion (The Devil's Rock) attached to direct, and Weta doing the effects. A few other novels are under option—Castaways, Kill Whitey, Darkness on the Edge of Town, and several more. And I've recently had some serious interest from a studio regarding The Last Zombie, although it's too early to talk about it more than that.

HC: What projects, books, comics, short stories, or anything else, do you have coming up?

BK: Several new novels. Pressure, which is sort of Alien meets Jaws. That comes out from St. Martin's next year. Suburban Gothic, my sequel to Urban Gothic, should be out from Deadite Press early next year, as well. And The Lost Level, which is my ode to Pellucidar and The Warlord and Land of the Lost. That will be out soon from Apex Book Company. Short story-wise, not much, other than X-Files stories for an anthology Jonathan Maberry is editing. And in comics, nothing that I'm allowed to talk about yet, but there's some stuff cooking.

HC: You mentioned in a blog post earlier this year (or maybe it was last year) that paychecks for a working writer, even a successful one like you, aren't as glamorous as many people would expect. This is pretty sobering news for aspiring storytellers. How "bad" or "real" is it? I've also heard anecdotally and off-hand that comic book writers aren't really paid that much (though no one has ever told me how little that amount actually is).

BK: I'd probably be making more if I'd become an HVAC technician or got an IT job, but I do okay. I'm a single dad with one son in elementary school and another in college. I'm not rich, and my Wednesday pull-list is bare bones (especially at today's cover prices), but the bills are paid and my kids are fed and at the end of the day, that's all you can really ask for from any job. Yes, writing for a living is incredibly hard. There's no 401K, no health insurance, and usually no chance of retirement. How many times a month do we hear about a veteran comics writer or mid-list genre novelist who are undergoing financial distress in what should be their golden years?

It happens all the time, and it's fucking terrifying because you know it's just a matter of time and a roll of the dice until that's you some day. You don't have those worries with other jobs. But at the same time, writing for a living offers rewards and freedoms that other jobs never do. For example, I make my own hours, which means I can devote more time to my kids than most working parents can. That alone is worth it right there. Also, I get to give back to a genre and a medium that has given me countless hours of entertainment and enjoyment throughout my life. If I get someone through study hall or their daily commute or a lonely night home alone, if I distract them from whatever is going on in their life that they don't want to think about, then I've done my job. I think that's a noble thing. Books and comics were always an escape for me. I like providing others that same escape. It's a hard job, but I wouldn't want to do anything else.

HC: So, if writing doesn't necessarily pay that much, what words of wisdom do you have for aspiring writers to prepare them for this road?

BK: Do it because you love it. Do it because you can't not do it. Novelist Tom Piccirilli has a saying: "If you're stranded on a desert island, and you write stories in the sand with a stick, then you're meant to be a writer." But it's also important to have a back-up plan, to have alternatives, because there will be lean times, and not just at the start of your career. And learn patience. You can be taught how to write, but it's harder to teach patience. And patience is one of the key elements to succeeding in this business.

Writer and videographer Hilton Collins loves sci-fi and fantasy wherever he finds it, whether it's in comic books, movies, books, short stories, TV shows, or video games. On the video side, he studies filmmaking, motion graphics, and animation; and on the writing side, he covers what he loves for Bleeding Cool and on his own blog, Imagination Unplugged (www.imaginationunplugged.com), a website about entertainment and self-help for creative professionals. He is @HiltonCollins on Twitter.