Posted in: Comics, Recent Updates | Tagged: barry windsor smith, batman returns, Comics, entertainment, erik larsen, frank frazetta, frank miller, Frederic Wertham, harvey kurtzman, jim lee, jim steranko, michael golden, micronauts, neil gaiman, Overstreet Price Guide, punisher, robert crumb, sandman, spawn, The Savage Dragon, tim burton, todd mcfarlane, Watchmen, x-force, x-men

Four Color Roots Part 4: X-Men, Image Exodus, Batman Redefined In Animation (1991-1992)

By Christopher Smith

In this, the fourth installment of our ongoing column series, Christopher Smith takes us on a tour through his own back pages as a comics fan, going down unexpected dark alleys and digressions. Focusing only on the comics and pop-cultural touchstones he experienced at the time, he reconsiders their (at times unlikely) influence and impact from a modern-day context, and his own journey through the four-color and geek culture worlds that's apropos of so many comics fans and pros of the same generation.

Last time, he launched into fandom full-on via the complex, multilayered storytelling of Larry Hama, thrilled to the Art Deco aesthetic of The Rocketeer, and got sucked into Spider-Man via Erik Larsen's kinetic storytelling. As our story resumes, our young hero—no more immune to sweeping trends than anyone else—starts to discover the X-Men…

Today, Malibu Graphics claims only about three and a half percent of the comic market. This hardy band of superhero creators is betting that comic book buyers will follow them to a new label the way record buyers might follow a rock star

– CNN news report on the founding of Image Comics, 1992.

Like many comic buyers of my generation, I picked an awful time to get into the X-Men. I had enjoyed the odd Classic X-Men reprint of the title's Claremont/Byrne heyday, even if I hadn't been able to piece together (or afford) a complete run of classic issues; I was left wondering how Hank McCoy and Jean Grey would make it back from the Antarctic wasteland until reading the Essentials volumes about fifteen years later. But 1991's record-shattering X-Men #1, which teamed Claremont with Jim Lee, was an auspicious beginning and that most coveted of all industry product-that-sells-itself phrases even today, the perfect jumping-on point for new readers!

At least, sort of. I had a multitude of questions about who all these characters just were, let alone the fact that its counterpart book was numbering into the high 200s at this stage and seemed more or less impenetrable. But the art was key. Lee brought something to comics which I had yet to see at that time, a combination of craftsmanship and vitality, the pop-art glamor of Patrick Nagel, or the angular models sizzling up the pages of Sports Illustrated that year in uncomfortable neon swimwear, with the hyper-realism and masculine heft of Frank Frazetta. It was designed perfectly for both the culturally-constructed pubescent psyche, as well as a far-reaching Zeitgeist that appealed to fans regardless of gender. Lee himself, who I had seen photographed in a few magazines and would increasingly so as Image Comics became more popular, radiated a kind of youthful, handsome, Asian-American cool perfect for the times. He was a rock star in the tradition of Barry Windsor-Smith or Jim Steranko. The artist was king and, until his abdication, would rule Marvel and skyrocket its sales. DC lacked this kind of figure, for now, and overall seemed more writer-centric to me when I'd begin reading its titles in earnest the following year.

For reasons now well-documented, this emphasis on illustration over writing in an editorial sense, led to Claremont's departure after the opening three-issue arc of X-Men. Being used to Hama's hundred-plus issue tenure on G.I. Joe, this was startling and somewhat upsetting. While I didn't have much of a frame of reference for what Claremont did so well, what was happening in his absence was rather confusing and uninvolving.

The first companion X-title that I purchased, the same month (October, 1991)'s Uncanny X-Men #281, was a bit of a letdown, despite its cover branding itself as "A MUTANT MILE-STONE!" While knocking the excesses of early 1990s comic book art is a bit of a hack pastime at this point and something I won't engage in very much, bear with me for a moment as I critique it a bit. The cover—by the talented Whilce Portacio, himself destined to become an Image co-founder—seemed somehow like an off-brand imitation of Lee's X-Men #1 cover art, as was perhaps an editorial mandate. Colossus flexed in an odd and certainly larger-than-life manner evocative of Schwarzenegger at his brawniest; the sleek bodies of Jean Grey and Storm bookended each other ornamentally while sporting open-mouthed facial expressions charitably described as odd; uber-detailed Sentinel circuits, a psionic blast, and electrical spray littered the otherwise unoccupied spaces of the page. I was actually much more fond of the rear half of the wraparound cover, and the intense in-flight path of mayhem wreaked by Archangel and his razor wings, which I think I'd read on his Marvel Universe card were the result of brutal posthuman experimentation at the hands of Apocalypse. Cool. We were now on the dawn of a second Toyetic Age, one that perhaps targeted us preteen oddballs. I desperately wanted an Archangel action figure, though I again thought the quasi-religious name would be considered blasphemous in my household. And wasn't I getting a little old for toys, anyway?

The other comics narrative that captured the grit and brutality of mutation in visual terms would be Windsor's-Smith's Wolverine origin story of sorts, Weapon X, which ran in eight-page installments between March and September of 1991 in Marvel Comics Presents. In each chapter, the perfect length for furtive spinner-rack reading without purchase—though I did end up with a copy of the first issue, which I bagged and boarded carefully—Logan was put through the rigors of more scientific engineering at the hands of Dr. Cornelius and Professor Thornton, the latter of whom resembled Michel Foucault. Most of the story transpired in a laboratory full of bacta tanks as seen in The Empire Strikes Back and the Serpentor storyline from the G.I. Joe cartoon series. With crowded panel layouts bursting with spiky adamantium bones and claws, multicolored hoses and fluids, and, finally, bloodshed as Wolverine turned on his captors and escaped into the snow, the sense of rage and captivity it contained and detailed with an almost loving intricacy made Weapon X the perfect dark escapist fantasy. Superhero comics are often called the power fantasies of the adolescent; in this story, the power was balanced by powerlessness and even (as a professor in grad school would later tell me she was writing about in reference to Wolverine in the X-Men films) the abject, itself an equally important aspect of the work.

Lee, meanwhile, would depart X-Men for Image, with 1992's #11 being his last issue. It was also the last I'd buy, or read, for about thirteen years.

The Image exodus was also a perfect metaphor for my entry into junior high, a kind of sea change. By fall 1992, everyone in my junior high school had shown up the first day of class wearing the then-ubiquitous Pearl Jam Ten t-shirt design and "Jeremy," the song and video presciently depicting a school shooting, was inescapable. Nirvana was big too, and I remember thinking the transparent, pregnant angel on the cover of 1993's In Utero belonged somehow to this horrifying aesthetic, spoke to the fragility of self, the pained vulnerability of the mutant outcast. My generation was mutating its own identity, and a new dark and eerie sonic and visual aesthetic had taken over, culminating in the late '90s Marilyn Manson brand of visually startling, mall-friendly gothic hard rock for conformist nonconformists. But I was out of comics by then, as were many of my peers, with hologram and foil-laced 1992 comics in closet shoeboxes taking up space. Rock and roll somehow did it better, more consistently.

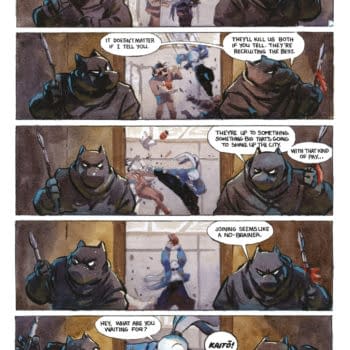

Image wasn't as dark and creepy, overall, favoring instead a flashy pin-up aesthetic of the sort Lee perfected, in addition to a promise of more mature themes in terms of sexuality and violence, free of the comics code; Erik Larsen's The Savage Dragon, for instance, promised a new direction of weirdly shocking (implied nudity and sex!) antics for superhero characters to get into. Already given a premium editorial freedom in terms of the grim content of his Spider-Man issues, Todd McFarlane's Spawn wasn't hugely different, but did contain a lurid and pitch-black aesthetic that also owed a bit to Frank Miller and Watchmen. While I like to think I was smart enough to avoid some trends, like the poly-bagged X-Force #1, which has become a punchline even outside of geek circles, and even scoffed at some of my classmates buying up overpriced Punisher #1s in droves at my first comic convention, I did hop onto the Spawn bandwagon for a bit. I seem to recall winning Spawn #1 in a convention raffle—or even as a prize for an NES Tetris contest that they held there, which my dad won—or perhaps only obtaining a copy once prices fell a bit, but did collect others, at least up until #10, the Cerebus guest-starring issue which I also purchased at a con. I think it was signed by Dave Sim. I couldn't tell you why I purchased it, only that I thought I might become a Cerebus fan after obtaining a free copy of 1993's #0. It has yet to happen.

While I wouldn't say I was old (or cynical) enough to detect something slightly forced amidst the evil clowns, serial killers, and assorted hideous hellspawn of Al Simmons' universe, I did find it quite comfortable in a less lurid but equally grim, unsubtle world of Tim Burton's Batman Returns, which premiered in the summer of 1992. By this time I'd seen and enjoyed the first film on home video—which featured a silly ad featuring Alfred hawking Diet Coke—but it was the sequel that truly connected with me. I was once again hyped to excess by the then-customary Topps souvenir movie magazine, with this one sporting a hologram on the cover. I read it cover-to-cover in anticipation of the film, feeling slightly smug that it explained to me inside jokes like Max Schreck (as played by Christopher Walken)'s name and the Paul Reubens cameo. I also appreciated the film on another level as a budding film fan, obsessing over details of the production design studied in this magazine and in others like Fangoria or Starlog. If Danny DeVito's bile-spitting Penguin seems a bit too ghoulish with hindsight, I was once again at the right age for the twisted fairytale sensibility that Burton brought to the mythos, in some ways literalizing the darkness of Miller for a mass audience, or simplifying it for a PG-13 viewership (a possible direction for Zack Snyder comes to mind).

In Burton's masquerade ball held in Gotham, everyone was a twisted, self-aware freak who burst free from societal confines, especially the meek Selina Kyle licked back to life by strays and reborn as the leather-and-stitches-clad Catwoman. If Batman '66 was like the oldies radio station I didn't realize was oldies at the time, suddenly this mind-melting spectacle was getting a mixtape of your cool older classmate's punk, grunge, and industrial CDs. While its countercultural star has never shone as brightly in the firmament, it connected perfectly with the alternative '90s ethos in a way that a film like Nightmare Before Christmas would the following year, providing a new cornucopia of fantasy for the younger Cure fans and the older Goths who were by this time deep into Neil Gaiman's Sandman. I saw Batman Returns on its opening weekend, with that same friend who'd once shown me Frank Miller's Batman on the bus. I don't remember what he thought of it; I probably talked his ear off about all the geeky production details during the car ride home.

Batman: The Animated Series premiered in September 1992, and just gave me more to rhapsodize about after school each afternoon, or at the lunch table the next day. It's amazing and it's very likely you've seen it, and agree with me. If, for some reason, you haven't, just take a minute to rewatch the intro. From the moment that "BANK" exploded onscreen in a moment scarier and louder than anything I'd seen in televised animation, I was fully hooked. The darkness of its cast of villains, and their tragic stories, engrossed me at the time, as did the Bruce Timm character designs the and backgrounds' Art Deco charm, as seen in The Rocketeer and the Fleischer Superman shorts which TNT would show a two-second clip of on its animation block each day, but maddeningly never in their entirety. Perhaps moreso than even the Burton films, B:TAS was the moment at which the character truly clicked for me, and became the one superhero I would read from now until the end of my first wave of comics fandom. Around the time I came back to comics in the early 2000s, imagine my surprise to learn that Jim Lee, of all people, was now drawing Batman. It was like the squaring of the circle at last. Twelve-year-old Chris would have been over the moon.

At the same time, I was a little exhausted with current comics, and they weren't cheap. I sought out something else, and in this case, had the happy accident of receiving (via one of my dad's co-workers) a copy of the Sotheby's auction catalog from its December 1991 Comics and Comics Art auction. Not only did this slim, blue hardcover introduce me to a world of shadowy power brokers engaging in the same speculative collecting game as all us preteens—they collected Jim Lee's original art, while we had to be content with grabbing doubles of the issues off the now-overflowing comic shop shelves—but it acted as a sort of Rosetta Stone of comics history. Each time I reread it obsessively, I learned something new. First, it introduced me to Namor's and Marvel's origins in 1939. Then, the EC artists, with whom I'd become vaguely familiar from Mad and the Tales from the Crypt TV series I'd seen little clips from at a friend's house, or on Entertainment Tonight. Then, there were eyestrain-inducing facsimile pages from Robert Crumb's 1989 tribute to Harvey Kurtzman. At this time, I only knew of Crumb as a lovable goofball trying to hunt down back issues he couldn't find. I related.

Then there was a compelling, bewildering page on the 1960s' underground comix era, including the truly puzzling (at this age) Joel Beck's Lenny of Laredo, and Jaxon's God Nose. It all fascinated me, the crudeness of the images and the splash pages of stories left untold; it was raw, cartoony, and even a little viscerally unsettling. Why were some of these comics labeled as "Adults Only"? I didn't know and wasn't sure I wanted to know, but these bizarre images stuck with me.

Of course, lest we think I'm painting myself as some sort of pint-sized Art Spiegelman, let me remind my readers that I was as eager to get a copy of November 1992's "Death of Superman" issue as anyone else. Only I was so eager to get home that day, to run inside, that I slipped on our driveway and tore my face up a bit. I think I still got my mom to take me to the store, and they were all sold out. I had to make do with a reprint; I didn't care much for the story.

Almost as intriguing as the Sotheby's catalog were the Overstreet price guides. (I did buy an issue of the much-ridiculed Wizard at one point, maybe for the chromium Lady Death card therein, but I avoided buying it, largely. It wasn't cheap, and that was money I could have been spending on the comics, themselves.) From their introductory chapters as well as books like 1993's uber-celebratory Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics, I had pieced together a workable history of comics, in broad brushstrokes. I became fascinated by Fredric Wertham, and his name always stuck with me, to the point where Seduction of the Innocent was one of the first books I went spelunking for in my college library six years later (I also watched Crumb on VHS around that time). At the same time, my world of comics fandom was cracking and being born anew, exploding out in different directions and vectors. Past issues and series were looking increasingly exciting to me, and were readily available and cheap in convention bins. As Nick Fury told Tony Stark at the end of Iron Man, I'd "just become part of a bigger universe."

Next time, we'll take a slight side trip in this chronological memoir to revisit the hairy, scary world of comic conventions in the early '90s. Were they a rough place for our author? Will he get elbowed out of the way by a seven-foot Mohawk punk eager to grab that Michael Golden Micronauts issue he needs for his collection? And will he be subjected to a harsh anti-MST3k jeremiad by a dealer with a true reverence for Gamera? The answer to one of these questions is yes.

Christopher Smith teaches composition at Columbus State Community College and has spent about two thirds of his life being obsessed with comics, music, and the strange, somewhat overlooked corners of pop culture. He lives with his wife, son, and two devious cats.